|

Walter John Dittmar (February 7, 1879 to October 23, 1964) | |

Selected Covers (Hover to View) Selected Covers (Hover to View) | |

Signing always as W.J. Dittmar, Walter Dittmar was born in 1879 to German immigrant John Frederich Ferdinand Dittmar and his Pennsylvanian wife Mary Schanbacher in Williamsport, Pennsylvania. He was the youngest of five surviving siblings, including Charles Frederick Elmer (1864), Emma A. (8/1866), William (3/1870) and Oliver Ferdinand (6/9/1872). The future artist was a life-long resident of Williamsport. Walter received no formal artistic training other than what was taught in high school, although his father was a woodcarver, which requires some level of artisan skill. In his late teens he was employed as a freelance illustrator with the Grit Publishing Company in Williamsport.

In the 1899 and 1900 Williamsport directories, Walter and Emma were listed as artists, with William, Oliver and Ferdinand listed as proprietors of the Dittmar Furniture Manufacturing Company. For the 1900 enumeration Walter was listed as an illustrator, Emma as an artist, and Ferdinand, Elmer and William as carvers.

In the 1899 and 1900 Williamsport directories, Walter and Emma were listed as artists, with William, Oliver and Ferdinand listed as proprietors of the Dittmar Furniture Manufacturing Company. For the 1900 enumeration Walter was listed as an illustrator, Emma as an artist, and Ferdinand, Elmer and William as carvers.

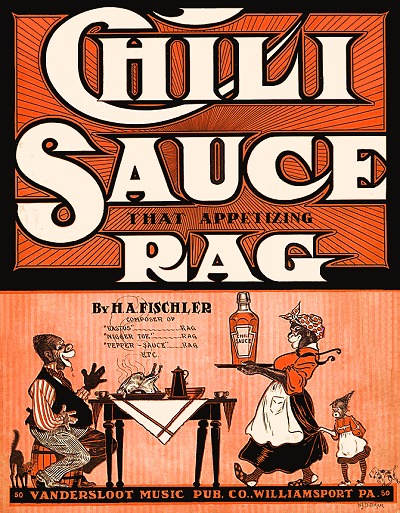

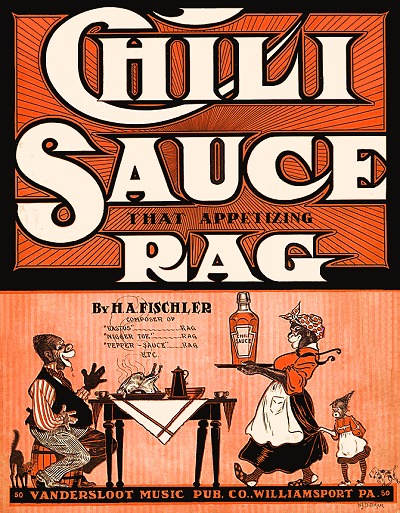

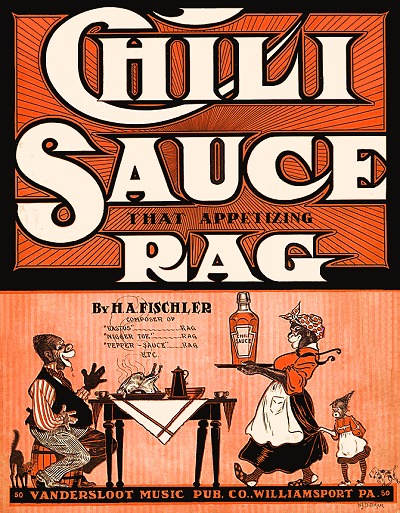

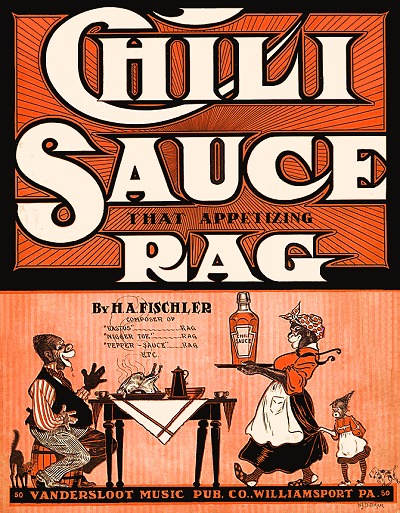

On April 15, 1903, Walter was married to Daisy Irene Scudder at her parent's home in Williamsport. From 1904-1914 or so Dittmar was the primary artist for the amazingly prolific Vandersloot Music Company. His covers adorned more than 100 music sheets published by the Williamsport company. Walter's parents were charter members of the First United Evangelical Church in Williamsport, and his brother William was a church worker who was in the choir and taught Sunday school. The family was heavily involved in Christian community, which brings up an enigma of sorts.

As was expected at that time, many of the rags and song publications from Vandersloot, as well as other publishers, were steeped in ethnic stereotype. So Dittmar could turn out a beautiful landscape for a sentimental piece one week, plus attractive drawings for the Herald, yet the next week produce some blatantly offensive images for rags that even included Nigger in the title. But accounting for the environment of that era (although not so much in rural Pennsylvania), work is work, and he did it well.

The 1910 census shows Dittmar as an independent artist with his own shop. Daisy had given him two children, Irene (1906) and John (10/1909). Irene's sister was living with the couple, and Walter's mother, sister, and brother William were residing next door. A few years later on his 1918 draft record, Walter's employer was shown as the local Herald Publishing House, which put out Christian materials. Little had changed by 1920 as the census showed that the Dittmar family seemed to all live in the same general block in Williamsport. Walter was still listed as an illustrator, although he eventually also taught art in the Williamsport school system from the 1920s to the 1940s. He further illustrated for a Williamsport-based monthly Christian magazine called the Gospel Herald, and for the Union Gospel Press of Cleveland, Ohio, from the 1910s to the 1960s, listing the latter as his employer on his 1942 draft record. By the time of the 1950 enumeration, taken in Williamsport, Daisy had died, leaving him as a widower, living with his daughter Irene and a granddaughter. Walter was listed as a religious artist, and Irene as his assistant artist. Walter passed on in 1964 at age 85 in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania. His daughter Daisy had carried on the family tradition by teaching art in secondary schools in Williamsport.

Of note in Dittmar's illustrations, which actually had quite a bit of variety between beautiful nature or romantic scenes and outright caricature, was his effectively sparse use of color. While it may have been a directive by Vandersloot in order to keep cover costs down, it was more likely because he was color blind, making management of multiple colors difficult at best. With just one color plus black he was able to create subtle shadings and halftones that filled out many details in a picture, even if tree leaves aren't really pale maroon. He also provided a great consistency for the Vandersloot output, much in the way that Hoen did for E.T. Paull, making the pieces from this publisher just as identifiable without having to look for the logo. Even on covers incorporating photographs Dittmar was able to make artwork out of an otherwise stiff looking band portrait.

Many thanks for additional information and verification go to the descendants of W.J. Dittmar, historian Alec Stevens, and the Lycoming County Historical Society.