Charles Leslie Johnson (December 3, 1875 to December 28, 1950) | |

Ragtime Compositions Ragtime Compositions

| |

|

1899

Scandalous ThompsonDoc Brown's Cakewalk 1902

A Black Smoke1906

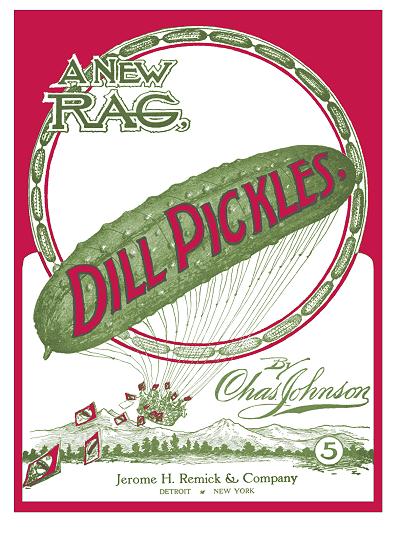

Dill Pickles Rag1907

Southern Beauties (aka Lovey Dovey)Sneeky Pete (aka Sneaky Peet) 1908

Fine and DandyAll The Money [1] Powder Rag [1] Beedle-Um-Bo [1] 1909

Apple Jack, Some RagPorcupine Rag Pansy Blossoms Silver King Rag Pigeon Wing Rag Kissing Bug 1910

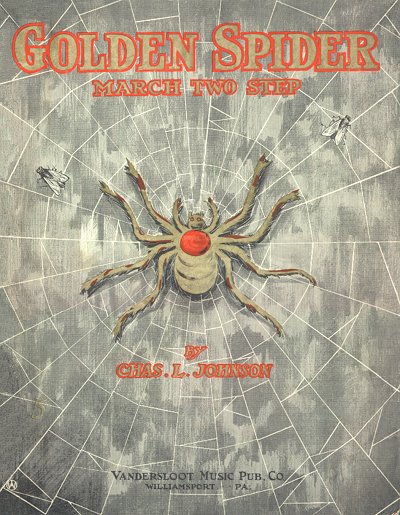

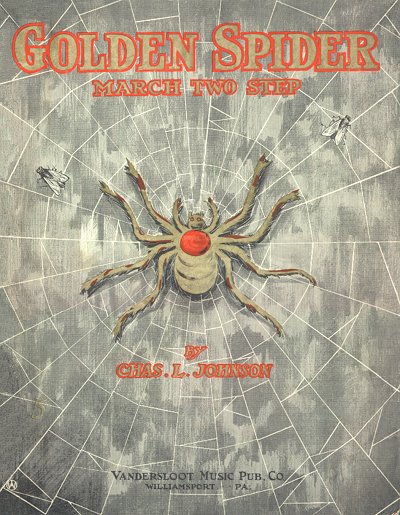

Golden Spider: Rag MarchUnder The Southern Moon: Two-Step Lady Slippers: Rag [1] |

1911

Cum-BacTar Babies: Rag The Barber Pole Rag Cloud Kisser [1] Melody Rag [1] 1912

Hen Cackle RagSwanee Rag 1913

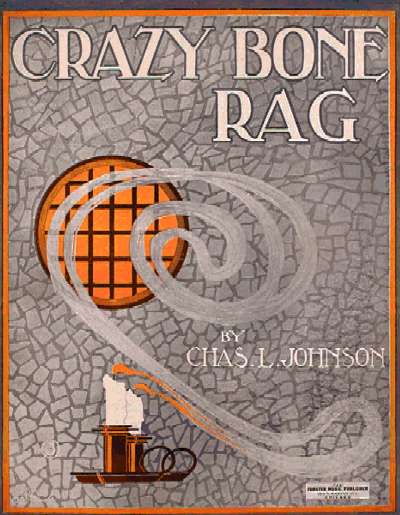

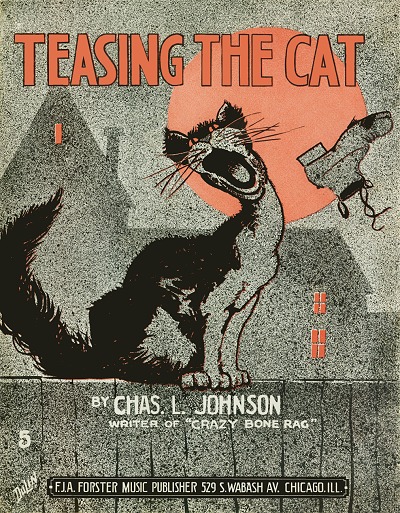

Crazy Bone Rag1914

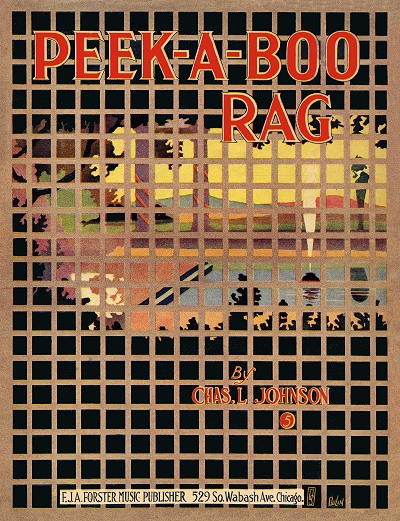

Pink PoodleHoneysuckle: Tango/Two-Step Peek-A-Boo Rag 1915

Alabama Slide: Fox Trot1916

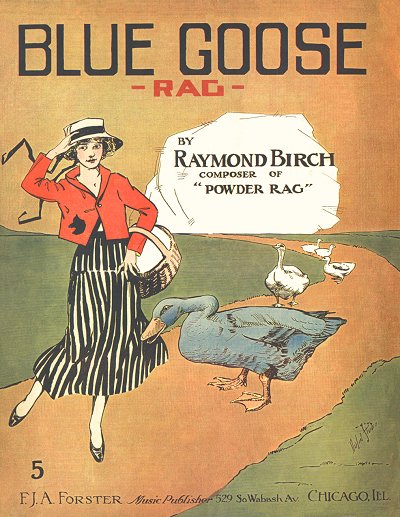

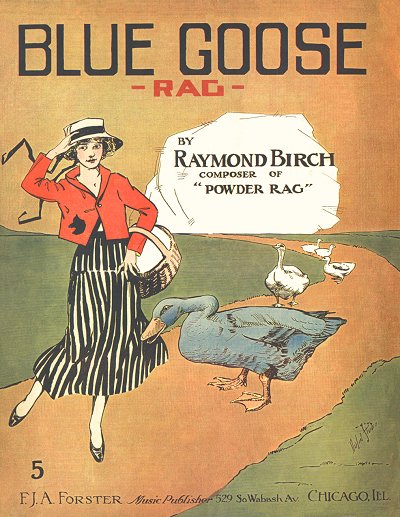

Blue Goose Rag [1]Teasing the Cat 1917

Fun on the Levee: Cake Walk1918

Snookums: Rag1928

Monkey Biznez - Novelty

1. As Raymond Birch

|

Songs, Waltzes, Intermezzos Songs, Waltzes, Intermezzos | |

|

1895

Crystal SchottischeEsquimaux: Dance Wayside Willie's March (Weary Walker) 1898

Warwick Club MarchGaytella Waltz 1899

A Love TokenThelma Waltzes Hester On Parade Belle of Havana: Waltzes It Takes a Coon to Do the Rag Time Dance [2] By the Winding Tennessee [3] In Far Away Manila [4] Smile On Me Again, Sweetheart [5] 1900

A Tally-Ho PartyWhen We Shall Meet Again [6] 1901

With Fire and Sword1902

The Blue Jay and The Squirrel1904

A Whispered Thought: NoveletteThe Louisiana Purchase: March Old Missouri's Good Enough for Me 1905

Iola - IntermezzoGood-Bye Susanna [7] When May and I Were Sweethearts Long Ago [8] 'Neath the Skies of California Far Away [9] Bonnie Eyes of Brown and Blue [6] I Don't Want to Go Away [10] 1906

Dedication MarchHymn to the Evergreen State [11] Iola - Song [12] My May Day Fortune [13] William Jewell [14] The Story That You Told Me in the Dell [15] As the Soft Shades of Evening Fall [16] The Little Girl I Loved but Left Behind [16] When the Blue Bells Bloom Again [17] 1907

That Little Sunny Southern Girl of Mine [18]My Mountain Rose [19] 1908

Charles L. Johnson's Barn DanceFawn Eyes: Intermezzo Fairy Kisses Waltz Butterflies: Caprice The Harvest Hop: Barn Dance With You [20] Alicia (Dream Name of my Dreamland Maid) [21] Patty [22] Dementia Americana [23] The Sunbeam of My Childhood Days [23] You Have Stolen My Heart Away [24] We'll Get Ham Again Some Day [25] Beneath the Shining Sun [25] Mary Kill Your Little Lamb and Get a Man [25] I'm Going to Love Her and Call Her My Queen [25] Stealing Kisses (Give Me Back that Stolen Kiss) [25] Magdalene [25] Deep in My Heart, Beloved [26] You Must Love to Tease Me [27] Maiden Blushes [27] Koy-o-to [27] Looking for Dixie [28] A Robin's Song [28a] 1909

Sunbeam: IntermezzoWedding of the Fairies: Waltz Fairy's Dream: Reverie Dixie Twilight Why Can't I Make a Hit? Tobasco: Rag-time Waltz Somebody's Smiling [27] If I Only Had a Sweetheart [29] Every Jack Must Have His Jill [30] They've Parted and Left Me [31] 1910

Heart Fancies: WaltzesYankee Bird: March The Blushing Rose: Serenade Woodlawn Waltzes Silver Star: Intermezzo Sweetheart [26] Sweet Genevieve [27] Dill Pickles (Song) [32] Little Star Won't You Twinkle [33] French Auto Cylinder Oil Waltz [34] Pueblo [35] When the Lilacs Bloom Again, Lolly Dear [36] My Love for Kentucky [36] 1911

Queen of Fashion: WaltzesDream of the Fairies: Waltzes Nearer My God to Thee: Variations The Girl for Me [20] Silver Star (Song) [20] Lucy Lee [20] Someday You'll Love Me [20] When I Dream of You [20] Fifty Years Ago (When We Were Wed) [20] Sly Old Moon [20] I'll Meet You On the Golden Shore [20] 1912

Golden HoursGolden Moon Henry's Slip'ry Slidin' Trombone School Life: March Two-Step Meet Me Where the Shadows Fall When You and I Were Sweethearts Long Ago I'm Goin', Goodbye, I'm Gone My Dreamy Rose [20] Only a Faded Rosebud [20] Alicia [21] Meet Me on the Santa Fe Trail [38] My World [39] 1913

Shadow Time: ReverieLucinda's Ragtime Ball Dream Days Fountain of Love: Waltz Charles L. Johnson's Picture Show Music Ma Pickaninny Babe [1] Down By the Old Garden Gate [20] Just a Duel of Love and Pride [39] Shadow Time: Song [40] When the Roses Fade Away [41] Meet Me in the Moonlight Carrie [42] The Years I've Spent With You [43] 1914

Summer Breezes: WaltzesDream-On: Waltzes When You Dream of the Girl You Love You're the Girl That I've Been Longing For [44] Down Where the Trail Divides [45] 1915

Cassandra WaltzesU.S.S. Texas March One Night in Mexico When the War is Over [29] In the Hills of Old Kentucky (My Mountain Rose) [40] I'll Be Waiting for You [40] Roses Bring Memories of You [46] 1916

Doodle-De-DumDear Little Home Sweet Home If I Only Had a Girl Like You Croon Time [40] It's the Closest Place to Heaven (Where the Little Shamrock Grows) [47] That Story of Beautiful Love [45] Old Glory Unfurled [48] 1917

Moonlight Love: IntermezzoI Never Thought I'd Miss You So (Until You Went Away) [29] Golden Hours: Song [40] We Will Follow the Red, White and Blue [47] I Like the Name of Dixie (But I Love My Northern Home) [49] I Can See Your Face in Every Sparkle of My Diamond [50] When We Make the Kaiser See Stars, Then He Will Respect the Stripes [51] Short Skirt Girls [52] Dreaming of You [53] What's the Combination to Your Heart? (I Want to Steal Your Love) [54] Moonlight Love: Song [55] 1918

Starlight: SerenadeSweet Memories: Waltz Beautiful Island of Dreams (Come with Me) [7] Our Yesterdays [56,57] Our Boys Over There (Under these Flags) [58] Queen of Our U.S.A. [58] Old Glory [59] We Are All in the Same Boat Now [60] What Sherman Said was Right (War is Hell) [60] Be a Pilgrim (And Not a Ram) [61] Far Across the Ocean Blue (Good-Bye, Little Girl, I'm Going Far Away) [62] Rose of Tennessee [63] Our Sammies [64] The Kaiser's Military "Ball" [65] |

1919

Moonlit Waters: Reverie [56]Sweet and Low [44] Where the Lanterns Glow [44] Sweet Nora McSheen [66] Kansas: The Gem of Our Nation [67] Pollyanna [68] 1920

May Breezes [56]Valse Decembre [56] 1921

Wanda: Fox TrotBy the Silvery Nile [69] Isle of My Love [69] Old Familiar Songs My Mother Used to Sing [70] My Star of Gold [71] 1922

Spanish MoonEverybody Calls Her Sunshine [72] Colorado and You [72] Because You Answered Yes, Etjedene [74] 1923

When Clouds Have Vanished and Skies AreBlue [20] 1924

Spangles [56]Can You Bring Back the Heart I Gave You? [20] Sweetheart With You [74] 1925

Ten Compositions for the Piano [75]Blue Bells (A Flower Song) Witching Moonlight (Waltz) Night Wind (Waltz) Whirlagig (Galop) Bobolink (Waltz) Cascade (Arpeggio Waltz) Tinkle Bells (Galop) Golden Slipper (Gavotte) Little Gray Mouse (Caprice) American Cadet (March) I Want to See My Pickaninny (In the Heart of Old Virginny) [76] The Sweetheart Trail [77] Laddie Boy [78] 1926

Dreaming, Still Dreaming of You [79]Retrace [80] 1927

Over the Old Back FenceThe Painted Picture [81] I Love You Old Missouri [82] Three and Twenty [83] The Wild Prarie Rose [84] 1928

Your Cause and Mine [85]1929

Happy Go Lucky Gal [86]My Missouri Cabin[87] 1930

Come Back Tonight in My Dreams1933

Drifting Along in a Lover's Dream [56]1934

You Owe Your Dear Mother That Too [88]1935

Dear LouWhen I Am Gone [89] 1936

He's For Us AllJubilee in the Sky [90] Bungalow Town [90] 1938

Ava-Jean [91]1939

In the Good Old U.S.A.Carry Me On Old Pardner [90] 1940

March of the Air CadetsOver Here [92] Good for Nothin' No-a-count [93] 1941

Fair Nebraska1943

The Red and the White and the BlueWeb of Love Row, Row, Row 1946

In the Old Doorway [94]My 'Loved Delaware [94] Smile On Me Again, Sweetheart [95] 1947

My Little Woman1949

Harlequin Revels

1. As Raymond Birch

2. w/Robert G. Penick 3. w/Malcolm Nicolson 4. w/James R. Noland 5. w/Ada Jones 6. w/Robin Reid 7. w/Milton G. Harsha 8. w/George H. McCrary 9. w/Frank Harold French 10. w/Raymond G. Hogarty 11. w/Fred Santee 12. w/James O'Dea 13. w/M.F.C. Hardman 14. w/Vincent Dye 15. w/Joe P. Fern 16. w/F.J. Munagle 17. w/Wellington Guston 18. w/J.E. Jeter 19. w/Lou E. Schaeffer 20. w/William R. Clay 21. w/John G. Winter 22. w/Clara D. Gilbert 23. w/Alva Snyder 24. w/Gilbert Moyle 25. w/Louis E. Gerber 26. w/Addison Madeira 27. w/J.P. Hingtgen 28. w/Florence Williams Brantley 28a. w/Jaen Flower 29. w/Robert Spencer 30. w/George Creel 31. w/Oscar Reser 32. w/Alfred Bryan 33. w/Tell Taylor 34. w/Anthony D. Holthaus 35. w/Fred Fox 36. w/Julius Neihart 37. w/M.N. Eisner 38. w/Jack Riley 39. w/Lillian Sheridan 40. w/James Stanley Royce as J.R. Shannon 41. w/Martha B. Thomas 42. w/Hamilton S. Gordon 43. w/C.L. Butterfield 44. w/James Stanley Royce 45. w/Harry Reynolds 46. w/Ben L. Morgan 47. J.W. O'Connell 48. w/Charles W. McClure 49. w/Hale Byers 50. w/Coral Marsh 51. w/A.T. Rubin 52. w/Thomas Barnes 53. w/Rollie Moore 54. w/Maxwell Jesse Janes 55. w/Raymond B. Egan 56. As Herbert Leslie 57. w/Francis Lake 58. J.C. & May Ferguson 59. w/Eunice Campbell Shannon 60. w/Mabel Beck & Marvin Westerman 61. w/George Cordell 62. w/William E. Roush 63. w/Frank Watkins 64. w/Sidney L. Goodley 65. w/Charles S. Guilford 66. w/John Fenton 67. w/John Timothy Carrington 68. w/Bessie Stopherd Cabibi 69. w/Jack Yellen 70. w/Mary L. Wilcox 71. w/Luella Stutzman 72. w/Carson Jay Robison 73. w/Alice Richardson 74. w/Harry Gile 75. As Eugene Edgar Ballard 76. w/Nellie Doud Allen 77. w/Al Neal 78. w/Edward Boyd Graham 79. w/Paul Alexander 80. w/Della Dora Thea Bauer 81. w/Mina H. Richards 82. w/Josephine Ellis 83. w/Rene Millar 84. w/Fred R. Cottrell 85. w/William Oliver McIndoo 86. w/Lee Turner & Lotta Greene 87. w/Grace Lewis Vandiver 88. w/Lloyd A. Calkins 89. w/Marion Gilmore 90. w/Louis J. Bennett 91. w/Ben. & William Williamson 92. w/Louis A. Savidge 93. w/Bayard Mosby 94. w/Edgar Ponder Elzey 95. w/Katie Joyce |

Unpublished Works Unpublished Works | |

|

Across the Sands

After the Rain Comes My Sunshine Annabella The Army, the Navy, and Marines Baby Doll Because I Love You So Cactus Pete Carlotta The Coppers on Parade The Cowboy's Lament Dance of the Midgets Dear Little Lady Dear Little Rose Desert Moon Dreamin' Tonight of My Darlin' Ev'ry-Thing I Do Seems Wrong Forgive and Forget Girls (1923) Go' Long Jasper Goin' Back to My Hometown in Sunny Tennessee Good Morning Mr. Sunshine Graceful Gunner Bill Hand in Hand He's My Pappy High School March Hittin' the Trail Hold Me in Your Arms Hold Me in Your Arms Again Honey Don't Be Mean to Me Honolulu Lou I Got a Gal in Arkansaw "I Have No Name for This" (quote at the top of the piece) I Love Somebody I Love the Ladies I Never Thought I'd Miss You So I Want a Man (not titled) I Wonder if You Ever Think of Me I'm a Ho-Bo (not titled) Idaho In the Cradle of the Rockies In the Twilight Glow It May Be Just a Notion (That's All) Jesus Will Welcome You Home Johnny Don't Be Mean to Me June Time [w/Eva Otis] Just a Quaint Old Melody Just a Sweet Old Melody Just You Keep Smiling and You Can't Go Wrong Let's Dream Back to the Day We Met Let's Paint the Old Town Red Lonesome Little Girl Love Mammy Jinny's Lullaby Maybe Meet Me By the Haystack, Sadie Memphis Buddy's Swing-Time Band [w/Eva Johnson] |

Midgets on Parade

Mississippi Shore Missouri (three parts for male quartet) Mother's Arms My Arabian Rose My Heart's in Dixie Today My Old Home [2] Nancy Jane Oh You Man On a Honeymoon (Just We Two) On Our Golden Wedding Day On the Banks of the Winding Tennessee One Kiss, and Then Goodnight Our Battle Song [6] Out in the Golden West Overture Packin' My Grip, Headin' for Home Pappy Don't Care for Onions Paradise Trail Peace to the World (Good Will Toward All) Ploddin' Along Roll Deep River Roll Roll on Brothers Rural Capers Send Me a Rose [2] She's Irish Snooty Little Cutie [Eva Johnson?] The Soldier's Farewell [w/Charles J. Hellinger] Somewhere Somewhere on the Deep Blue Sea Song of the Bride Song of the Soul Spooky Blues Steppin' On the Gas Sunshine and Moonlight Sweet Girl [2] Sweet Ida May That Jones Girl Tell Your Troubles to the Moon There Never Was, There'll Never Be Uncle Billy Untitled (Two different works without titles or words) Up in the Air with Sally The Voice on the Radio Waltz (not titled) When I Found You When Mother Rocked Baby to Sleep When the Boys Come When the Frost is on the Clover When the Toot-Toot Toots for Memphis Tennessee While I'm Away Why Did You Leave Me You Don't Want Me Around Anymore You, Just You (words and melody similar to "Just You") You're the Sweetest Girl I Know |

Charles L. Johnson was born in Armourdale, Wyandotte, Kansas (now part of south Kansas City) to James R. Johnson and Helen Elizabeth Dilley. As Armourdale and Wyandotte were eventually incorporated into Kansas City, the Kansas side of that metropolis is considered his birthplace by default. Many Federal census records and Johnson's 1918 draft card show him to be a year older than the commonly published 1876 date suggests.

So, he was most likely born in 1875 as the 1880 census, 1910 census, 1930 census and his World War I draft card specifically claim or mathematically imply. In 1880, James was shown to be a fisherman, and his wife a housekeeper. Charlie was evidently an only child, as no siblings were seen in subsequent records for Kansas or Missouri. There was no occupation listed for James in the 1885 Kansas State census.

|

Charlie was attracted to the piano at a very early age, even though the Johnsons did not have one in their home. After having taken some lessons from a neighbor lady on whose piano he also practiced, his natural abilities encouraged his parents to buy him a piano when he was around nine. Charlie took formal study in classical music until his early teens, when popular music tugged at his heat continually. While studying Beethoven, he was also playing the popular hits of the day on the sly. This did not serve Johnson well when his new teacher, Professor Kreiser, became frustrated by these non-classical piano outbursts, so Charlie quit taking the lessons.

The youngster continued to learn, though, taking courses to better ground him in music theory and compositional skills, as well as picking up the banjo, guitar, brass, violin, drums and mandolin, enabling him to play with small groups, as well as the George Washington Juvenile Military Band. The 1895 Kansas State census showed James, Helen (enumerated as Ellen) and Charlie now living in Kansas City, Ward 2. James' occupation was shown as "leisure," which may have indicated a temporary retirement, but his son was now working as a music teacher at age 19.

Johnson lived his entire life in Kansas City, much of it on the Missouri side, which was across the state from the center of ragtime activity in St. Louis. He was not all that far from Sedalia, although that town had a relatively short active ragtime life of a few years. There is some evidence that the word "rag" may first have been used in Kansas City in the 1880s or earlier in relation to a dance event or the music played for it. While there was certainly some good ragtime both played and published in Kansas City, it would become a more prominent music center in the 1920s when early swing music was taking shape.

While there was certainly some good ragtime both played and published in Kansas City, it would become a more prominent music center in the 1920s when early swing music was taking shape.

While there was certainly some good ragtime both played and published in Kansas City, it would become a more prominent music center in the 1920s when early swing music was taking shape.

While there was certainly some good ragtime both played and published in Kansas City, it would become a more prominent music center in the 1920s when early swing music was taking shape.Charlie's earliest tunes were performed by small ensembles, but not published except for a handful of them. He was a member of the Walton Mandolin Club during that time period and one of the members arranged a folio of arrangements and compositions that the group played. Among the first of Charlie's releases was Wayside Willie's March published by J.R. Bell of Leavenworth, Kansas, in 1895. Bell also released a few more Johnson pieces under their imprint, but most were string group arrangements. One of the first mentions of him in conjunction with music appeared in a local newspaper, the Kansas City Journal, on May 26, 1898. Johnson had a tune featured at the commencement exercises of the Kansas City, Kansas, high school, a march appropriately titled The Class of '98', played by Zeiler's Orchestra. Whether Johnson was playing with the group or not is unclear.

By 1898 Charlie was working as a piano and music demonstrator for J. W. Jenkins' Sons Music Company in Kansas City. Having already placed a couple of compositions with them, he managed to get his foot in the recently opened ragtime door with a fine instrumental, Scandalous Thompson, which Jenkins released in early 1899. This was closely followed by Doc Brown's Cake Walk the same year, a piece allegedly based on a local character who is pictured on the cover. Jenkins managed to get an arrangement of this to bandleader John Philip Sousa when he was in town. The Sousa Band's performances of the tune helped to make it fairly popular in short order. In their advertising, Jenkins also featured pieces such as Thelma Waltzes and A Love Token mixed in with other popular tunes of the day. Johnson played three of his selections at the Home Products Show in April. By the end of the year his few published pieces were heavily featured in Jenkins' advertising.

After a fairly robust showing in 1899, for the next couple of years there were but a few of Charlie's songs and incidental piano solos appearing in print. Johnson's first business cards and magazine advertisements indicate that he was in the music arrangement and commissioned composition business, in which he met limited success in the early years. In the 1900 census he was shown still living with his parents in Kansas City, Kansas, now listed as a musician. His father was working again, this time as a claims agent, likely for an insurance company. Later data suggests he would soon be or was already in training to become an attorney.

Charles was married on June 21st, 1901, to Sylvia Hoskins. Their daughter Frances was born the following year but died in infancy. At some point in 1901 Charlie jumped ship from Jenkins and went to work for the Carl Hoffman publishing house.

His first piece published under their imprint was the dynamic 1901 march, With Fire and Sword. In 1902 they issued A Black Smoke, one of his more interesting and highly syncopated folk rags. There are rhythmic elements of the piece that suggest it to be a train-oriented song, somewhat in the manner of his friend and fellow Kansas City composer Charles N. Daniels' 1902 hit Hiawatha. The cover suggests otherwise, showing a black child smoking a cigarette, but cover designs were often derived for sales and currency, not necessarily a reflection of the intended nature of the work.

|

There was a lull in writing activity for Johnson in 1903, but he fired back in 1904 with a good-sized hit. With the growing success of Hiawatha, the supposed train-oriented song that actually launched the fad for Indian-themed pieces, Charlie came out with a similar intermezzo of his own. Iola did quite well as an instrumental, and then late in the year it was also made into a song just as Hiawatha had been. Both pieces were named after towns in Kansas, not after Native American figures or cultural icons, but as the towns had originally derived their names from Native Americans, there was an indirect linkage. Curiously it was not published by Charlie's employer, but instead by Central Music. Copies under that imprint are hard to find as the company dissolved within a couple of years, and the plates and rights to both versions of Iola were sold to the Jerome H. Remick firm after it acquired Daniel's company. They kept it in print for many years.

Iola became a point of controversy over three decades later in 1940 with the publication and recording of a big band piece called Playmates, much of which sounded very suspiciously like Johnson's tune. While some may have forgotten the earlier piece by that time, the composer had not, and with current copyright owner Jerry Vogel he did battle against the Santly-Joy company which owned Playmates. By 1944, Johnson and Vogel received a decent settlement for the case of potential plagiarism.

In the 1905 Kansas State census, James was now listed as an attorney, a vocation he would hold for the rest of his life. As Missouri had no census at that time, Charlie and Sylvia were difficult to locate, but still living on the eastern side of Kansas City. His name was seen in various advertisements for music, and he also advertised on his own in music publications as an arranger for hire. One publisher that took him up on this was Tolbert R. Ingram of Denver, Colorado, and several pieces around 1905 to 1906 show up with Johnson writing music to various lyricists. Many still reside in the Ingram Collection at the University of Colorado at Boulder.

It was in 1906 that Charles L. Johnson officially became a composer of popular ragtime, as he concocted his biggest rag hit, Dill Pickles. It was allegedly named quite by happenstance. As it has been traditionally told, Charlie was working late at Hoffman's, composing his new rag. Another employee in the building, sometimes identified as the janitor, asked him what he was working on. Johnson saw the worker's dinner in his hand, which included a box of dill pickles, and decided that Dill Pickles would be the name of the piece. The body of the A section featured a secondary rag theme or three over four ragtime pattern that would soon be used commonly by Tin Pan Alley composers, such as George Botsford and George L. Cobb, and most notably by Texan and part-time Kansas City resident Euday Bowman for his 12th Street Rag.

Another employee in the building, sometimes identified as the janitor, asked him what he was working on. Johnson saw the worker's dinner in his hand, which included a box of dill pickles, and decided that Dill Pickles would be the name of the piece. The body of the A section featured a secondary rag theme or three over four ragtime pattern that would soon be used commonly by Tin Pan Alley composers, such as George Botsford and George L. Cobb, and most notably by Texan and part-time Kansas City resident Euday Bowman for his 12th Street Rag.

Another employee in the building, sometimes identified as the janitor, asked him what he was working on. Johnson saw the worker's dinner in his hand, which included a box of dill pickles, and decided that Dill Pickles would be the name of the piece. The body of the A section featured a secondary rag theme or three over four ragtime pattern that would soon be used commonly by Tin Pan Alley composers, such as George Botsford and George L. Cobb, and most notably by Texan and part-time Kansas City resident Euday Bowman for his 12th Street Rag.

Another employee in the building, sometimes identified as the janitor, asked him what he was working on. Johnson saw the worker's dinner in his hand, which included a box of dill pickles, and decided that Dill Pickles would be the name of the piece. The body of the A section featured a secondary rag theme or three over four ragtime pattern that would soon be used commonly by Tin Pan Alley composers, such as George Botsford and George L. Cobb, and most notably by Texan and part-time Kansas City resident Euday Bowman for his 12th Street Rag.There are a number of factors that contributed to the success of Dill Pickles. For starters, the unusual and creative cover showing copies of the rag being dropped from a giant dill pickle dirigible with the name across the side was instantly eye-catching. The piece itself was accessible to most pianists with reading capability, and easy to pick up by ear as well. The B section had a catchy trombone slide figure in the left hand that further identified the work. With a band it was often used as dance music as well.

The plates and copyright for Dill Pickles were eventually sold to Remick, and with their promotion it became an outrageously successful piece. Charles N. Daniels was now a manager for Remick, and he likely had something to do with the acquisition of Dill Pickles and other Hoffman properties around that time. As was often the case with such successes, there was an attempt to turn it into what became a nearly unsingable rag song as well, an effort likely not endorsed by the composer, and which ultimately fell flat. Copies of the song are difficult to locate a century later. But the rag continued to thrill and delight. From that point on, Johnson's overall output was quite remarkable in terms of both volume and quality as well as commercial viability. Dill Pickles was just one of four of his rags which reportedly sold over a million copies each during his lifetime.

The success of Dill Pickles helped to both encourage and finance Johnson's entry into running his publishing firm. The initial incarnation of the Charles L. Johnson Publishing Company set up shop in the Braley Building in Kansas City, Missouri, in early 1907. Many of Johnson's own rags after 1906 utilized the secondary rag, or three over four pattern he had first used in Dill Pickles. Since they were generally easy to play and memorize, his products sold briskly. Simplicity worked well for his style, and he was widely regarded for his work by many fledgling composers who asked him for advice or even sent in works for Charlie to arrange. But he was also admired for his versatility. Johnson was just as adept at turning out a ballad or intermezzo as a popular rag.

In 1907 only four pieces were issued by Johnson, two of them in the ragtime vein, including the lovely Southern Beauties. It had started out as Lovey Dovey, but when Daniels acquired the copyright for Remick he thought a more suitable name could be applied. Sneaky Pete (or Sneeky Peet) sounded as if it might have been composed a few years before, but was also acquired by Daniels in short order.

The following year saw a big increase in both instrumentals and songs from Charlie, including his catchy Powder Rag and the more classic sounding Beedle-Um-Bo. The latter had an unusual and creative modulation in it, progressing from the opening key of F into Db for the trio, then back to F. Because of the number of rags, songs, intermezzos and other forms that Charlie had started composing in increasing numbers, he used the pseudonym Raymond Birch for some of his rags and songs. He would later use Herbert Leslie and Eugene Ballard from time to time for songs and instrumentals, but Birch was his primary pseudonym during the ragtime era. Part of this may have been so as to not "flood the market" or dominate his catalog with his own works.

As a sidebar, it should be pointed out that suggestions in print and on the web that Johnson used the names Fannie Woods and Ethel Earnist as pseudonyms for two of his pieces have been proven to be false, as both of these lady composers have been clearly identified and their parentage of their respective works properly established. With all due respect to those who continue to assert that Johnson wrote Sweetness, the author notes that there are articles in the Louisville, Kentucky paper from 1912 citing Woods playing her composition, and that the piece was dedicated to Woods' future husband. It is also unlikely that Johnson, living in Kansas City, would have even known Fannie's future husband who was also living in Louisville. Earnist was also a musician living just outside of Kansas City, and there is a great deal of data to support her authorship of Peanuts, and one other piece recently discovered, but issued by a different publisher. Hopefully the doubters in the case of Ms. Woods and Ms. Earnist will review the collective evidence and realize that if Johnson published pieces composed by other women for which he did not receive compositional credit, it is probably true for these two as well.

Many of Johnson's compositions from 1908 and 1909 were in the format of intermezzos, waltzes and dances. However, his rag output increased once again in 1909, as did his reach. Even with his own company, he found it lucrative to sell his copyrights to other publishers, and not just Remick. Two such pieces include his Porcupine Rag, which was distributed by M. Witmark of New York, and Apple Jack: Some Rag, which somehow got into the hands of Vandersloot Music in Williamsport, Pennsylvania. Manager and composer Harry J. Lincoln had gained a reputation for the company through the release of several other local rags – albeit none of his own at that time – so Johnson may have simply taken a chance on this somewhat rural company with a wide reach, working through mail. No details of the transaction have been found. Another commonly found piece from that year was the Pigeon Wing Rag, published by Harold Rossiter in Chicago. One other additional piece is his self-issued intermezzo Sunbeam, which had one of the more beautiful covers issued under the Johnson imprint, as did his rag Pansy Blossoms.

It is important to note that while Johnson was selling off his better material for a healthy profit, he was at the same time making it possible for other lesser-known composers, many of them women, to have their own rags found in music stores around the Midwest. Some standouts include The Tickler by Frances Cox, Twinkles by Charles A. Gish, Peanuts by the aforementioned Ethel Earnist, and Peach Blossoms and Slivers, both by Maude Muller Gilmore. The latter is more commonly known as Splinters, renamed as such when Harold Rossiter acquired the copyright and plates. Only the title changed and all other aspects remained the same. While Johnson was a relatively small publisher and distributor, Rossiter had a more extensive reach, and he may have either been responding to or heading off an issue with Slivers. There was another rag named Slivers composed by Harry Cook which was also released in 1909. It was explicitly composed for Barnum & Bailey Circus clown Frank "Slivers" Oakley. He had been using Slivers by Cook for a comic baseball routine he had been doing for several years. Rumors of any suits threatened or launched against Gilmore or Rossiter have not been substantiated, but it is possible that such a contention might have spurred the name change for Gilmore's fine rag. Other women published included Kate Myers Stith, Enola Kempka, Elva Tarlton, and Lucy B. Phillips.

Only the title changed and all other aspects remained the same. While Johnson was a relatively small publisher and distributor, Rossiter had a more extensive reach, and he may have either been responding to or heading off an issue with Slivers. There was another rag named Slivers composed by Harry Cook which was also released in 1909. It was explicitly composed for Barnum & Bailey Circus clown Frank "Slivers" Oakley. He had been using Slivers by Cook for a comic baseball routine he had been doing for several years. Rumors of any suits threatened or launched against Gilmore or Rossiter have not been substantiated, but it is possible that such a contention might have spurred the name change for Gilmore's fine rag. Other women published included Kate Myers Stith, Enola Kempka, Elva Tarlton, and Lucy B. Phillips.

Only the title changed and all other aspects remained the same. While Johnson was a relatively small publisher and distributor, Rossiter had a more extensive reach, and he may have either been responding to or heading off an issue with Slivers. There was another rag named Slivers composed by Harry Cook which was also released in 1909. It was explicitly composed for Barnum & Bailey Circus clown Frank "Slivers" Oakley. He had been using Slivers by Cook for a comic baseball routine he had been doing for several years. Rumors of any suits threatened or launched against Gilmore or Rossiter have not been substantiated, but it is possible that such a contention might have spurred the name change for Gilmore's fine rag. Other women published included Kate Myers Stith, Enola Kempka, Elva Tarlton, and Lucy B. Phillips.

Only the title changed and all other aspects remained the same. While Johnson was a relatively small publisher and distributor, Rossiter had a more extensive reach, and he may have either been responding to or heading off an issue with Slivers. There was another rag named Slivers composed by Harry Cook which was also released in 1909. It was explicitly composed for Barnum & Bailey Circus clown Frank "Slivers" Oakley. He had been using Slivers by Cook for a comic baseball routine he had been doing for several years. Rumors of any suits threatened or launched against Gilmore or Rossiter have not been substantiated, but it is possible that such a contention might have spurred the name change for Gilmore's fine rag. Other women published included Kate Myers Stith, Enola Kempka, Elva Tarlton, and Lucy B. Phillips.For the 1910 enumeration Charles was listed as a music publisher in Kansas City, Missouri, still living with Sylvia. Apparently no further attempts at having children were made as she is shown as already having had and lost one child. Charlie's parents were still residing over the Kansas state line, with James again listed as a practicing attorney. Johnson's ragtime output dropped a bit, but he still had at least two first rate pieces under his own name. Under the Southern Moon is questionable as a piano rag, and actually sounds very much like a three part song, indicating that there may have been some intent in that direction. The title certainly suggests as much. Golden Spider was a very intricate rag in which you could hear the lattice of the lacy web being formed. It was the second of his works published by Vandersloot music, and the last, as he may have been frustrated with the lackluster speed of promotion and distribution, in spite of the very nicely rendered cover. It still sold in large quantities over time, and is quite collectible today.

After more than three years in business, the prolific Mr. Johnson sold his firm for a tidy sum to the Harold Rossiter organization in August 1910. It was allegedly on the condition that he not enter the publishing business again for at least one year. But with his output and reputation, Johnson had no trouble getting published by other music houses during that time. In spite of the agreement, Charlie was back in business for himself by January 1911 as the Johnson Publishing Company. He also continued to worked both free-lance and on retainer as an arranger during the decade, so there are many more pieces than we may ever know of that Johnson was responsible for putting in print. This would continue for the next two decades as he engaged in the practice that some have referred to as the song-poem firm, where a company advertised music written to a poem, and then published. Most firms simply printed off copies for a profic and sent them back to the composer. Charlie actually was more above board, publishing little, but sending back nicely rendered melodies to the person who submitted them Ironically, some of those made it into print by song-poem firms such as the one run by the questionable H. Kirkus Dugdale of Washington, DC.

Perhaps it was meant as an inside joke. In 1911 Charlie released the very popular Melody Rag as composed under his pseudonym Raymond Birch, yet "arranged by Chas. L. Johnson." To further the joke, it was one of several parodies of the 1910s based on Anton Rubinstein's famous Melody in F. One other ubiquitous work was Tar Babies Rag with a mildly offensive name and cover, but still frequently found in antique malls around the country. Also in the catalog were many songs by Johnson and other composers, and some more Indian-themed intermezzos. Among these was his own Silver Star of 1910, which was repurposed as a song under the new imprint. Charlie also made an overture to movie pianists, being among the first composers or publishers to offer music specifically for them. For $1.00 they got a packet of 24 thick cards with musical selections intended for picking and choosing to accompany various moods or action on the screen.

Charlie also made an overture to movie pianists, being among the first composers or publishers to offer music specifically for them. For $1.00 they got a packet of 24 thick cards with musical selections intended for picking and choosing to accompany various moods or action on the screen.

Charlie also made an overture to movie pianists, being among the first composers or publishers to offer music specifically for them. For $1.00 they got a packet of 24 thick cards with musical selections intended for picking and choosing to accompany various moods or action on the screen.

Charlie also made an overture to movie pianists, being among the first composers or publishers to offer music specifically for them. For $1.00 they got a packet of 24 thick cards with musical selections intended for picking and choosing to accompany various moods or action on the screen.Before 1911 was out the imprint again changed to "Published by Chas. L. Johnson," then in 1912 back to "Chas. L. Johnson Publishing Company." Just the same, the majority of Johnson ragtime compositions and instrumentals from mid-1912 on were published by F.J.A. Forster Music Publishers, and even a couple by Cincinnati publisher Sam Fox. Charlie retired from the publishing business by early 1913 and Forster would obtain some of his copyrights for reprints. F.J.A. Forster was a growing concern in Chicago started by Fred John Adam Forster who would soon become one of Johnson's best colleagues in the business, as well as a social friend of the family. Johnson's contributions to the catalog in turn helped Forster grow even more in the 1910s.

In spite of his new alignment with Forster, Johnson compositions still turned up in the Remick and Fox catalogs, as well as under the imprints of Maurice Richmond, George W. Meyer, Dearing and Dietz, M.B. Thomas, Hamilton S. Gordon, the Universal Music Company, J.W. O'Connell, Rollie Moore, Ted Browne and Reynolds, Larson & Company. It can be ascertained that in some of these cases Charlie was providing music for lyrics by or from that publisher, and many of these compositions are the only one under each imprint. Some were also the result of his melody-for-hire business. Just the same, it made tracking his output difficult at the very least. He also did some fine arrangements of piano rags, one of them being Pickled Beets by Ed Kuhn published by Jenkins' Sons in 1912.

One of the other big hits from the pen of Charles L. Johnson was released by Forster in 1913, although it was not an immediate success. Crazy Bone Rag was potentially written to be performed by a pianist accompanied by a bones player. The bones were sometimes actually rib bones, but more often wood shaped like rib bones, used between the fingers of one hand to create percussive rhythms. The cryptic cover provides no clues on this possibility either way. The rag fairly swings, and in some respects is Dill Pickles turned on its side. While it was a steady seller in its time, like Dill Pickles it would become popular during the 1950s honky-tonk piano craze. One of the first recordings was done by performer Frankie Carle in 1952, but it was easily eclipsed in the mid 1950s by the hit single performed by Johnny Maddox, who played it well into his eighties on a regular basis more than a half century later.

Both 1913 and 1914 were busy years for Johnson songs and instrumentals as well, the most prescient of them being Shadow Time, released as both a "reverie" and a song in 1913. He also wrote a late period "coon" song, My Pickaninny Babe, and although it was a well-crafted lullaby with a tasteful cover, such titles were rapidly going out of vogue. Summer Breezes of 1914 is also still frequently found. His most arguably interesting piece of that year was Pink Poodle, an unusual rag that sounds more elegant when played at a slower tempo, which appeared to be the intention. It had habanera passages scattered throughout and harmonically was very adventurous. While the bold blue and pink cover caught the attention of the consumer, his Peek-A-Boo Rag was even more interesting with an interesting lattice suggesting the title. Taking the habanera idea further, Johnson also composed Honeysuckle Tango. The majority of his pieces during this period were released by Forster.

He also wrote a late period "coon" song, My Pickaninny Babe, and although it was a well-crafted lullaby with a tasteful cover, such titles were rapidly going out of vogue. Summer Breezes of 1914 is also still frequently found. His most arguably interesting piece of that year was Pink Poodle, an unusual rag that sounds more elegant when played at a slower tempo, which appeared to be the intention. It had habanera passages scattered throughout and harmonically was very adventurous. While the bold blue and pink cover caught the attention of the consumer, his Peek-A-Boo Rag was even more interesting with an interesting lattice suggesting the title. Taking the habanera idea further, Johnson also composed Honeysuckle Tango. The majority of his pieces during this period were released by Forster.

He also wrote a late period "coon" song, My Pickaninny Babe, and although it was a well-crafted lullaby with a tasteful cover, such titles were rapidly going out of vogue. Summer Breezes of 1914 is also still frequently found. His most arguably interesting piece of that year was Pink Poodle, an unusual rag that sounds more elegant when played at a slower tempo, which appeared to be the intention. It had habanera passages scattered throughout and harmonically was very adventurous. While the bold blue and pink cover caught the attention of the consumer, his Peek-A-Boo Rag was even more interesting with an interesting lattice suggesting the title. Taking the habanera idea further, Johnson also composed Honeysuckle Tango. The majority of his pieces during this period were released by Forster.

He also wrote a late period "coon" song, My Pickaninny Babe, and although it was a well-crafted lullaby with a tasteful cover, such titles were rapidly going out of vogue. Summer Breezes of 1914 is also still frequently found. His most arguably interesting piece of that year was Pink Poodle, an unusual rag that sounds more elegant when played at a slower tempo, which appeared to be the intention. It had habanera passages scattered throughout and harmonically was very adventurous. While the bold blue and pink cover caught the attention of the consumer, his Peek-A-Boo Rag was even more interesting with an interesting lattice suggesting the title. Taking the habanera idea further, Johnson also composed Honeysuckle Tango. The majority of his pieces during this period were released by Forster.In his capacity as a Kansas City plugger for Forster, who was located in Chicago, Johnson had the opportunity to introduce a potential hit which he had arranged. The Missouri Waltz (Hush-a-bye Ma Baby), composed by John Valentine Eppel with lyrics added by Charlie's friend and sometimes co-writer James Stanley Royce (as James Royce Shannon), was a lovely tune that he simply could not seem to sell to the public or other musicians. He ended up calling it a "flivver," referring to the erstwhile nickname for the much maligned Model T Ford, and gave up. It started to gain ground in the late 1930s. Once Harry S. Truman became president in 1945, The Missouri Waltz caught on and was finally adopted as the Missouri State Song on June 30, 1949, 18 months before Charlie's death. As for Truman, he claimed to have not cared so much for the piece.

Thanks to the still steady sales, and now piano rolls and recordings of Dill Pickles Rag, Forster was able to do well by Charlie in getting his products distributed and sold. The Alabama Slide, more of a fox-trot than a rag, made a big splash in 1915, as did Johnson's Cassandra Waltzes. But in 1915 the big topic on everybody's mind was the war that had started in Central Europe in mid-1914, and was now escalating as other nations took sides. War songs were quickly in vogue, not because the United States was all that close to being involved in the conflict, but because so many immigrants in the U.S. had a familial stake in what was happening. Some American soldiers volunteered in the British, French or Belgian armies, so were going off to war without help from Uncle Sam. So Charlie followed suit and wrote some war-related pieces in 1915, including one dedicated to the warship U.S.S. Texas, and the usual separation-from-loved-ones type of ballads.

So Charlie followed suit and wrote some war-related pieces in 1915, including one dedicated to the warship U.S.S. Texas, and the usual separation-from-loved-ones type of ballads.

So Charlie followed suit and wrote some war-related pieces in 1915, including one dedicated to the warship U.S.S. Texas, and the usual separation-from-loved-ones type of ballads.

So Charlie followed suit and wrote some war-related pieces in 1915, including one dedicated to the warship U.S.S. Texas, and the usual separation-from-loved-ones type of ballads.After a light year of piano rags, Johnson fired back in 1916 with two, both of them still very popular in the 21st century. Blue Goose Rag had a delightful cover, and was a highly melodic piece. The 32 bar trio had no syncopation and was clearly intended as a lyrical fox-trot. Since then it has been a favorite of historian David A. Jasen, and one of the staples of the author's performing friends Jeff and Ann Barnhart, who have turned it into a magnificent variegated opus. Teasing the Cat is a fun work full of little dissonances, and somewhat similar in concept to pieces being issued by Mel Kaufman around the same time. Again, the clever cover was one of the highlights of the work. It and many other Johnson works were featured in a special concert at the Scott Joplin Ragtime Festival in Sedalia, Missouri, in 2014.

There were several more tunes released that same year, but nothing significant. Charlie had resurrected his own publishing imprint one last time, and in 1916 and 1917 was focused to some extent on releases by other composers under his label. He only contributed a handful of his own in 1917, two of them through his own company. In addition, the war was starting to deplete the supply of musicians everywhere, so Johnson was called on more often to perform with local groups or as an accompanist

Charlie's September 12, 1918, last call draft card showed him again as music publisher, and also as employed by the Jack Riley Orchestra. It further implies he was no longer married to Sylvia at this time, as his mother is listed as his nearest relative and no wife shown. With jazz on the way and the ragtime craze fizzling, Johnson released only one more piano rag titled Snookums Rag. The rest of his future output would consist primarily of songs and waltzes. The song Our Yesterdays was the first in which he used a new pseudonym derived in part from his middle name, Herbert Leslie. There were also a number of more aggressive war songs. This would also be the last year he published anything under the Charles L. Johnson Music Publishing Company imprint. One of Johnson's biggest non-ragtime hits came in 1919 with Sweet and Low, a song that reportedly earned him $30,000 while it was in print. However, Charlie's output slowed considerably from 1920 to 1924.

For the 1920 census James, now 76, was still listed as a lawyer in general practice. The couple continued to reside on the Kansas side of Kansas City. Charlie married once again on January 25, 1920, to South Dakota native Eva Otis, who was some 17 years younger than her new husband. The timing is such that he may have been off on his honeymoon when the census enumerators came to call, as extensive searches have found neither of them in the 1920 record. Upon their return the couple moved into a new home at 648 West 59th Terrace in the Brookside suburb of Kansas City. During this period both Johnson and Forster were making good profits from his prior works.

Charlie was still playing with local groups, and probably took some time off as well to simply enjoy his new marriage and accumulation of wealth. But he did not stop completely. There were a few Johnson arrangements that showed up during this period, but nothing significant. Most of what came out were light ballads and dance numbers, including a couple of 1921 songs co-authored with Jack Yellen, who had worked for many years with composer George L. Cobb. As Herbert Leslie he edited a Jenkins folio of Favorite Melodies from the Standard Operas.

James died sometime around 1925, and Helen Johnson moved in with Charlie and Eva. That year he introduced yet another Johnson pseudonym, Eugene Edgar Ballard. It is possible that since he had written a series of pieces for younger or less experienced pianists that he preferred his real name not be directly attached. The set of ten Compositions for the Piano were released separately rather than in a folio. Surprisingly, given the climate of the times, Charlie also wrote the music to a pickaninny song composed by Nellie Doud Allen, a relatively rare and somewhat tricky topic by 1925. From the early 1920s on a lot of Johnson's work had been writing or arranging music for vanity publications by other composers who went on to publish it themselves. Judging by some of those that remain, he may have been glad they were printed in small quantities due to the often inane lyrical content which read like poor prose. Still, he received a standard fee for completion of each submission, as that is what he was in business for.

Output slowed again from 1926 forward. Johnson arranged a tribute composed for aviator Charles Lindbergh in 1927 titled Our Yankee Boy. In 1928 Charlie made one last go at ragtime, this time in the novelty vein. Monkey Biznez was a decent novelty tune, but the composer found it hard to compete against the brilliant works of Roy Bargy, Arthur Schutt, or even Zez Confrey. He also threw his musical hat into the political arena with Your Cause and Mine in support of Republican presidential candidate Herbert Hoover. As the Republican convention was being held in Kansas City that year, there was assurance of exposure for the tune.

Now in his mid-fifties, he appears to have tried to balance retirement and work, turning out songs at a very leisurely rate. He wasn't done quite yet.

|

The 1930 census showed Johnson to still be a composer of music, and living with his wife Eva and widowed mother Helen in Kansas City, Missouri. The Great Depression had yet to really set in at the beginning of the year in spite of the stock market crash the previous October. But for musicians and composers big changes were very close at hand. Americans feeling the pinch, which by 1932 was almost everybody, were quickly weaning themselves off of sheet music and records. Many had already acquired radio sets, and that medium, paid for by advertisers, became the dominant source of musical entertainment in the 1930s. Vanity publications no longer paid the same dividends, yet Charlie continued to engage in them from time to time. He finally had to give up his nice house and had to relocate into a small apartment where the couple spent several years.

Among Johnson's best friends were the Fred Forsters, and the couples socialized quite often as Charlie and Eva visited Chicago several times. In Kansas City he was active for many years with an annual event called the Nit Wit Show run by the University Club. While writing only sporadically in the 1930s, he entered publishing once again, this time with Louis J. Bennett whom he had known for many years. Note that it has been suggested that around this time Charlie was also writing some novelty tunes under the name Moran Moore. However, research has ascertained that Johnson was not responsible for any of these tunes, as copyright records reveal the actual composer to be his friend Bennett. One of the first releases of the Johnson-Bennett company in 1936, which came more than four decades after Charlie had started composing, saw another relative success. Radio broadcasts and a recording of his Jubilee in the Sky by Fred Waring and His Pennsylvanians got some attention, and even Waring himself personally wrote to Johnson thanking him for the tune submission.

Most of what Johnson was involved with over the next three years was arranging, with scant compositions appearing under a variety of labels. There was a bit more activity in 1940, including a military piece geared towards the Army Air Corps and a patriotic song from the year before, In the Good Old U.S.A., extolling the virtues of the "land of the free." Also in 1940, Charlie was publishing on his own again with another round of the publishing company of Charles L. Johnson. This one survived a little more than a year.

He continued his playing gigs, and newspaper notices showed him performing before and during the war at the Country Club in Loose Park, the Hotel Baltimore, the President Hotel, and at least two decades working as an arranger for the American Royal livestock association, all located in the Kansas City area. Charlie also continued to be cited in conjunction with the University Club Nit Wit shows. In the 1940 enumeration taken in Kansas City, Missouri, Charles and Eva were shown living in the same home they had shared for many years at 3028 Tracy Street, with Charles listed as a musical arranger occupying his own office.

|

In 1941 Johnson finally joined ASCAP nearly three decades after it was founded, adding him to the ranks of other famous Tin Pan Alley composers who had started the organization. On his lifetime body of successes, Johnson was quoted as saying that he was "merely striking the popular fancy of the multitude; hitting on a waltz, a ballad, of a bit of ragtime that will be hummed eternally once it gets to going. Charlie also continued to write and arrange, with some of his arrangements done for the Grand Ole Opry in Nashville, Tennessee. It was discovered after his death that he had written a great deal more material that had not been published, some of it for the local shows, and some of it perhaps written into the late 1940s. Much of it currently resides at the Kansas City Library. Even at age 70, Johnson was able to contribute to no less than three tunes in 1946. His final publishing company was formed with his friend Kenneth R. Barnum that year, and survived until just after his death. Johnson's last known composition, Harlequin Night, appeared in 1949 when he was 73 years old. The 1950 census showed him still listed as a musician and music arranger.

Charlie's final years in Kansas City were spent with friends and family at his home on Tracy Street in Kansas City, especially with his doting spouse Eva. On at least two occasions she also directly involved herself with Charlie's work, contributing lyrics to two unpublished works, June Time and Memphis Buddy's Swing-Time Band, the dates of which are unknown. As mentioned in the late Phil Stewart's pioneering book on Johnson, Eva appears to have also composed her own piece, Snooty Little Cutie (In the Flat Next Door), which was also not published. A copy was provided to him by her nephew Harley Otis. She managed to win a prize for it in a Radio Guide contest held in 1939. It is possible she also contributed lyrics to some of Charlie's published works, but remains uncredited for that work.

Charlie died peacefully just three weeks after his 75th birthday, and is buried in Oak Grove Cemetery in Kansas City. Eva survived him until December of 1986. Concurrent with his death in December 1950 was a rising surge in the recording industry promoting a resurrection of ragtime era material, of which Dill Pickles would play a major role as one of the more popular rags. Lou Busch, Dick Hyman, Del Wood, Frankie Carle, and most notably, Johnny Maddox would give his piano rags a new life that continues into the 21st century. One of the biggest proponents of Charles L. Johnson piano rags from the mid-1990s on is the author's good friend Sue Keller, who has probably recorded more works by the composer than anybody else in history. The fine work of collector Phil Stewart has also uncovered many pieces that were unknown or simply suspected to exist. Dill Pickles remains a favorite at 21st century festivals, played more often than not by two or more pianists at one time. What is important, and what would make Charlie smile, is that they are being played - and thanks to loyal fans, listened to as well. Ain't that grand?

Acknowledgement should be given to collector and historian Phil A. Stewart of Kansas who has done the most extensive research on Johnson, all of which was a helpful augmentation to the demographic, public records and library collection research done by this author. He has also compiled the most extensive list of Johnson compositions available, and has a book and a separate music folio available on Johnson, both of which are highly recommended. The author was able to find even more compositions listed in copyright records during a 2016 rewrite of this essay, in which several corrections and enhancements were also applied. The list of unpublished works is from the Kansas City Library which houses the official Charles L. Johnson papers. Thanks also to Adam Swanson for additional Johnson information and Sue Keller for keeping the vibe alive.

Please note that as mentioned in the text, Sweetness by Fannie Bell Woods and Peanuts: A Nutty Rag by Ethel Earnist are not included in the lists or the biography as Johnson pseudonyms which was previously believed to be the case. The identity of both women as the true composers of those works has been absolutely verified with great detailed proof to back this contention up, a point which surprisingly has still not conceded by a select group of Johnson devotees. The respective biographies of these women along with a detailed explanatory document on the findings can be found in the Female Ragtime Composers section.