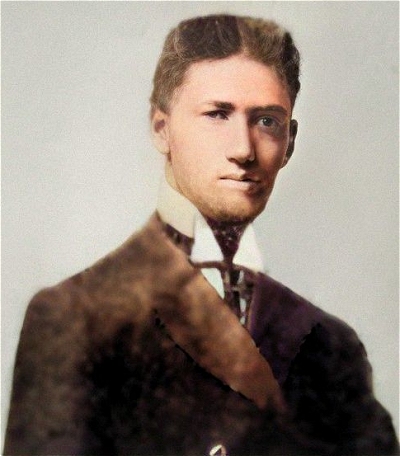

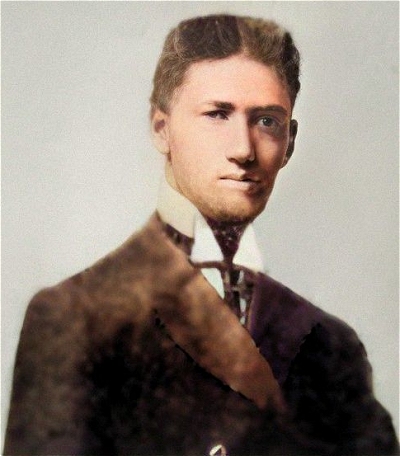

Clarence Hamer Woods (June 19, 1888 to September 30, 1956) | |

Compositions Compositions | |

|

1903

Meteor March1912

Slippery Elm Rag1914

Rusty Nails (Castle Walk)Parazade (Valse Hesitation) 1915

Pray for the Lights to Go Out[w/Clyde Olney] 1916

The Graveyard Blues [w/John S. Caldwell]The Worried Blues [w/Leroy Williams] 1918

Sleepy Hollow Rag |

1919

Who's Been Playin' Papa 'Round HereWhile I've Been Gone? Fever Heat [Rag Novelty - Piano Roll] Black Satin [Fox Trot - Piano Roll] 1938

Oklahoma, I Love You [w/Opal HarrisonWilliford] 1944

Salute to the Blue and White1947

Oklahoma Military Academy March1949

Oklahoma, U.S.A. (Suite) |

Born in Blue Earth, Adams County, Ohio to Samuel Chase Woods and Margaret "Maggie" Beekman, Clarence Woods was raised in both eastern Kansas and Carthage in southwest Missouri. Note that some sources list him as H. Clarence Woods, but multiple US census and local census records clearly list him as Clarence H. Woods (Hamer after his grandfather Daniel Hamer Woods), and his World War I draft record shows him simply as Clarence Woods, as he rarely used his middle name or initial. The 1895 Kansas census showed the family in Girard, Kansas, but they moved across the border to Carthage before the year was out. His father was a blacksmith, and he had two younger brothers and two younger sisters, including Claude Beckman (6/1888), Marguerite J. (1/1892), Gladys M. (9/1893) and Bryan W. (6/1896).

The 1895 Kansas census showed the family in Girard, Kansas, but they moved across the border to Carthage before the year was out. His father was a blacksmith, and he had two younger brothers and two younger sisters, including Claude Beckman (6/1888), Marguerite J. (1/1892), Gladys M. (9/1893) and Bryan W. (6/1896).

The 1895 Kansas census showed the family in Girard, Kansas, but they moved across the border to Carthage before the year was out. His father was a blacksmith, and he had two younger brothers and two younger sisters, including Claude Beckman (6/1888), Marguerite J. (1/1892), Gladys M. (9/1893) and Bryan W. (6/1896).

The 1895 Kansas census showed the family in Girard, Kansas, but they moved across the border to Carthage before the year was out. His father was a blacksmith, and he had two younger brothers and two younger sisters, including Claude Beckman (6/1888), Marguerite J. (1/1892), Gladys M. (9/1893) and Bryan W. (6/1896).Clarence was in the midst of a virtual hotbed of ragtime music as he grew up. Once he was living in Carthage, he took piano lessons at the Calhoun School of Music from the same teacher as James Scott, three years his senior, but how well they knew each other is uncertain. Both had their first compositions published by Charles Dumars, owner of Dumars' Music in Carthage as well, with Woods contributing Meteor March just after Scott's first two rags, but slightly in advance of his On the Pike.

In his late teens, Woods started traveling outside of Missouri into Oklahoma and Texas, playing for stage plays and Vaudeville olios with the Bleeding Hearts Stock Company. He also found some work with silent films, and in other accompanist positions. His performance skills eventually saw him lauded in print as the "Ragtime Wonder of the South." Woods spent several years in Fort Worth, Texas, starting in 1907, and many of his early compositions were copyrighted there. This included his first folk rag, Slippery Elm, published by Bush and Gerts in 1912. Clarence was married by early 1913 to Marie E. Woods, and Clarence Hamer, Jr., later known as Duke, was born on November 6, 1913, in Fort Worth. He also self-published his pieces Rusty Nails and Parazade in Fort Worth that same year. Some published arrangements by Woods appear in Texas during the 1914 to 1917 period. The couple eventually found their way back to Missouri, and in early 1917 he was listed at a Carthage residence of 301 N. Main, playing for movies at the Sho-To-Al Theater. By 1920 Woods and the family had moved north to Nevada, Missouri, and he was now playing for movies at the Star Theater plus other area engagements.

Woods spent several years in Fort Worth, Texas, starting in 1907, and many of his early compositions were copyrighted there. This included his first folk rag, Slippery Elm, published by Bush and Gerts in 1912. Clarence was married by early 1913 to Marie E. Woods, and Clarence Hamer, Jr., later known as Duke, was born on November 6, 1913, in Fort Worth. He also self-published his pieces Rusty Nails and Parazade in Fort Worth that same year. Some published arrangements by Woods appear in Texas during the 1914 to 1917 period. The couple eventually found their way back to Missouri, and in early 1917 he was listed at a Carthage residence of 301 N. Main, playing for movies at the Sho-To-Al Theater. By 1920 Woods and the family had moved north to Nevada, Missouri, and he was now playing for movies at the Star Theater plus other area engagements.

Woods spent several years in Fort Worth, Texas, starting in 1907, and many of his early compositions were copyrighted there. This included his first folk rag, Slippery Elm, published by Bush and Gerts in 1912. Clarence was married by early 1913 to Marie E. Woods, and Clarence Hamer, Jr., later known as Duke, was born on November 6, 1913, in Fort Worth. He also self-published his pieces Rusty Nails and Parazade in Fort Worth that same year. Some published arrangements by Woods appear in Texas during the 1914 to 1917 period. The couple eventually found their way back to Missouri, and in early 1917 he was listed at a Carthage residence of 301 N. Main, playing for movies at the Sho-To-Al Theater. By 1920 Woods and the family had moved north to Nevada, Missouri, and he was now playing for movies at the Star Theater plus other area engagements.

Woods spent several years in Fort Worth, Texas, starting in 1907, and many of his early compositions were copyrighted there. This included his first folk rag, Slippery Elm, published by Bush and Gerts in 1912. Clarence was married by early 1913 to Marie E. Woods, and Clarence Hamer, Jr., later known as Duke, was born on November 6, 1913, in Fort Worth. He also self-published his pieces Rusty Nails and Parazade in Fort Worth that same year. Some published arrangements by Woods appear in Texas during the 1914 to 1917 period. The couple eventually found their way back to Missouri, and in early 1917 he was listed at a Carthage residence of 301 N. Main, playing for movies at the Sho-To-Al Theater. By 1920 Woods and the family had moved north to Nevada, Missouri, and he was now playing for movies at the Star Theater plus other area engagements.Wood's ragtime output was small, but significant. Even though he had been on the road for some time he was still based in Carthage, his rags and blues heavily reflected the influence of the Jasper County area, with his Sleepy Hollow Rag named for a community on the Spring River near Carthage. Woods was more known as a performer than composer, although he co-wrote a few lesser songs and some early blues. One of his students clearly remembered that he never plowed his way through anything in his life.

Two of Woods' novelty pieces appeared only on arranged piano rolls, but both Black Satin and Fever Heat show signs of a clear understanding of that genre, one in which he did not follow up with more works. The 1930 census shows Marie and Clarence Jr. back in Carthage, but she was divorced from the traveling pianist. He had moved to Tulsa in the mid-1920s working mostly as a theater organist and pianist, listed as a theater musician. According to a niece of Woods he was living with his sister Gladys. However, the age, birthplace and other demographics for that Gladys found in the 1930 census taken in Tulsa, Oklahoma do not match this scenario. Since the Tulsa record also lists Gladys as "wife," and his sister Gladys Woods Moffett was found in living Carthage two days later, it can safely ascertained that Clarence was married once again around 1925, this time to Gladys Alsup of Tulsa. The same niece cast him as somewhat of a loner. Gladys Alsup died as Gladys Woods in 1989.

The 1930 census shows Marie and Clarence Jr. back in Carthage, but she was divorced from the traveling pianist. He had moved to Tulsa in the mid-1920s working mostly as a theater organist and pianist, listed as a theater musician. According to a niece of Woods he was living with his sister Gladys. However, the age, birthplace and other demographics for that Gladys found in the 1930 census taken in Tulsa, Oklahoma do not match this scenario. Since the Tulsa record also lists Gladys as "wife," and his sister Gladys Woods Moffett was found in living Carthage two days later, it can safely ascertained that Clarence was married once again around 1925, this time to Gladys Alsup of Tulsa. The same niece cast him as somewhat of a loner. Gladys Alsup died as Gladys Woods in 1989.

The 1930 census shows Marie and Clarence Jr. back in Carthage, but she was divorced from the traveling pianist. He had moved to Tulsa in the mid-1920s working mostly as a theater organist and pianist, listed as a theater musician. According to a niece of Woods he was living with his sister Gladys. However, the age, birthplace and other demographics for that Gladys found in the 1930 census taken in Tulsa, Oklahoma do not match this scenario. Since the Tulsa record also lists Gladys as "wife," and his sister Gladys Woods Moffett was found in living Carthage two days later, it can safely ascertained that Clarence was married once again around 1925, this time to Gladys Alsup of Tulsa. The same niece cast him as somewhat of a loner. Gladys Alsup died as Gladys Woods in 1989.

The 1930 census shows Marie and Clarence Jr. back in Carthage, but she was divorced from the traveling pianist. He had moved to Tulsa in the mid-1920s working mostly as a theater organist and pianist, listed as a theater musician. According to a niece of Woods he was living with his sister Gladys. However, the age, birthplace and other demographics for that Gladys found in the 1930 census taken in Tulsa, Oklahoma do not match this scenario. Since the Tulsa record also lists Gladys as "wife," and his sister Gladys Woods Moffett was found in living Carthage two days later, it can safely ascertained that Clarence was married once again around 1925, this time to Gladys Alsup of Tulsa. The same niece cast him as somewhat of a loner. Gladys Alsup died as Gladys Woods in 1989.The Great Depression was hard on many musicians, and some of the jobs held by itinerant or traveling musicians simply dried up or were at least sparse. So at the time of the April 1940 enumeration Clarence, who had been making his home in Tulsa through the late 1930s, was divorced (as evidently anticipated by some family members) and back in his adopted home of Carthage, Missouri. He was staying at the YMCA and working as an organist at the local skating rink. As World War II helped bring prosperity and hope back to America, things picked during the 1940s for musicians as well. Clarence led an orchestra, became a radio entertainer, and started composing more. His last pieces, largely unknown and unpublished, were written in his capacity of composer/arranger, primarily for concert band. He also reportedly wrote some tunes for the presentational needs of Ringling Brothers Barnum & Bailey Circus from approximately 1949 to 1953, where he also performed on the organ and steam calliope. The 1950 census taken in New York city was on brand, showing him as a musician in a travelling show. After having run away with the circus for a few years, Woods moved to Dallas, Texas to retire.

Clarence Woods died during a visit to his son's home in Davenport, Iowa. According to a notice published in Billboard on October 6, ironically a week after his death, "Clarence Woods, former organist with Ringling-Barnum, is confined to St. Luke's Hospital, Davenport, Ia., after surgery and would enjoy mail, writes his son, Duke Woods, of the Moline (Ill.) Dispatch." (Clarence, Jr., had been working for newspapers in Iowa since the late 1930s, and had been wounded and discharged from Army service in Austria in 1944.) Given the publication delays of that time, his death notice appeared in the following edition.

Thanks go to researcher Mitch Meador who provided some information about Woods' later Oklahoma compositions for concert band.