George Linus Cobb (August 31, 1886 to December 25, 1942) | |

Compositions Compositions | |

|

1905

Dimples: March)br />

Mr. Yankee: MarchYour Credit is Good: March 1906

FleetfootWestern Life: March The Chauffeur: March Pittsburg Exposition: March 1907

Parade of the Teddy BearsIdylia 1908

A Happy Group - Barn DanceI Love You Dear [w/R.G. Norton] 1909

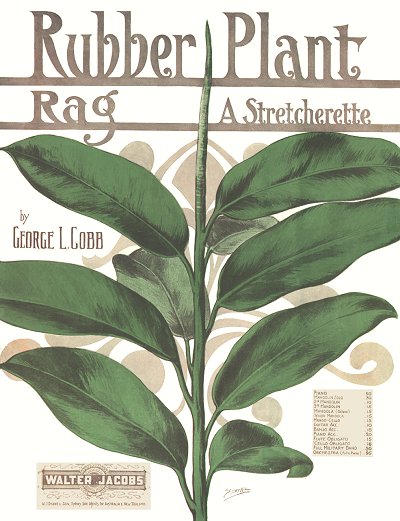

Rubber Plant RagBuffalo Means Business [2] Moonlight Makes Me Lonesome [3] 1910

Aggravation RagCanned Corn Rag That Hindu Rag (1910/1924) The High Brows: March Attar of Roses: Waltz I Used to Be Lonesome ('Till I Found You) [3] 1911

I'd Like to Take a Chance with You [3]Honey Lou! ('Neath The Big White Honey- Moon) [3] Make Your Hay While the Sun Shines, and Do Your Loving by the Moon [3] 1912

Jolly Dancers OstendeMister Melody Man Down On de Levee Every Little Note Means Love When Billy Plays That Way Lady Of The Lake Stunning Grenadiers Mister Melody Man Oh! That Lovey, Dovey Glide When Oscar Played the Flute The Baboon Bounce Enchanted Dale: Waltz Cheops: Egyptian Intermezzo Buffalo: City Song [4] 1913

Bunny Hug RagRoll Along Old Georgia Moon The Get-A-Way: March and Two Step I Long To Be Way Down In Tennessee Take Me Back To The Days Gone By Mist of Memory: Waltz Just For To-Night All Aboard for Dixie Land [3] Bring Me Back My Lovin' Honey Boy [3] Lonesome Moon [3] You'll Be Sorry [3] If I Find Another Boy Like You [3] On the Good Ship Nancy Lee [3] If I Only Had You Again [5] 1914

After-Glow: A Tone PictureKnock Knees: One-Step On The Q.T.: March Huskin' Time: A Rural One-Step Fleur D'Amour (Flower of Love): Waltz La Parisia: Hesitation Waltz Mona Lisa: Valse That Tangoing Turk: One-Step Sing Ling Ting Ta-Tao: Chinese One-Step On The Banks of Honolulu Bay Hero Of The Game: March Mammy's Golden Wedding Day [3] Mammy's Little Angel Child [3] On A Summer Night [3] Listen to That Dixie Band [3] I'm Coming Back in Springtime [3] That Tantlizing Tango Tune [3] A Holiday in Dixieland [6] Dance That Dengozo With Me: Oo-La-La [7] 1915

Rabbit's FootGolden Dawn: Tone Picture White Narcissus: Waltzes Buds and Blossoms: Waltzes Law And Order: March Brass Buttons: March Three Nymphs: Dance Classique Barbary: Valse Algerienne Young April: Novelette Virginia Sue Alabama Jubilee [3] That Twilight Melody [3] Are You From Dixie [3] It's All A Dream [3] Roses Mean Memories (Mem'ries Mean You) [3] On The Road To Dublin Town [3] On Honolulu Bay [3] Dancing 'Round the U.S.A. [3,8] You Didn't Care [9] 1916

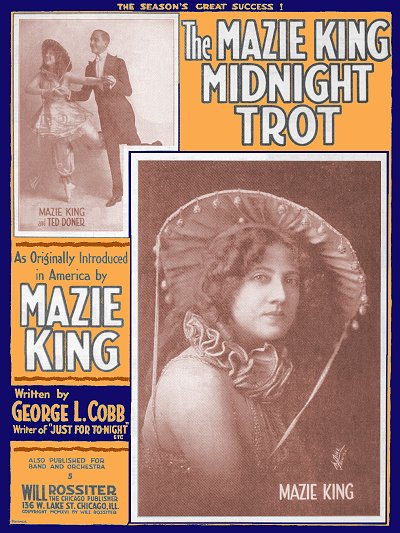

Mazie King Midnight TrotRed Rooster I'm Goin' To Hit The Trail For Alabam' Good Bye Blues Drift Wood: Novelette In The Beautiful Garden of Dreamland Frangipani: Fox-Trot Georgia Rainbow [1] There's Someone You've Forgotten Who Has Not Forgotten You [3] Twentieth Century Squaw [3] See Dixie First [10] When You Dream Of Old New Hampshire, I Dream of Tennessee [10] When You're Five Times Sixteen [10] Won't You Come and Love Me [11] I Can't Forget [12,13] With Bobbie in His Little Machine [14] 1917

Nautical Toddle aka Nautical NonsenseBlue Sunshine: Waltz Levee Land: One-Step Blue Bird: Waltz Down on Blue Bird Bay: One-Step Some Shape: One Step Down Where It's Always June When the Moon was Hanging Low Ladder of Love Waltz There'll Come A Night Waiting Bone Head Blues [1] Hang Over Blues [1] You and You: Waltz [1,15] Come On Down to Cincinnati Town [3] The Battle Song Of Liberty [3] Dreaming [5] The Picture That the Shamrock Brings to Me [16] All Aboard For Rock-A-Bye Bay [16] Send Me A Line (When I'm Across the Ocean) [17] Down on Blue Bird Bay [17] Mississippi Volunteers (Forward March!) [18] Columbia's Call [19] Good Goin' [20] 1918

Irish ConfettiRussian Rag Cracked Ice Rag Calcutta: Oriental Fox Trot Say When Peter Gink (Adapted from Peer Gynt) Toy Poodles: Novelty One-Step Moonbeams: Novelette What Next!: Fox-Trot Here's How: One-Step Treat 'Em Rough: One-Step Peek In: Chinese One-Step Sunshine (Spread All the Sunshine You Can) Opals: Waltz [1] |

1918 (Cont.)

My Little Pal [1,18]In the Glow of the Alamo Moon [3] When the Lilies Bloom in France Again [18] In the Old Front Parlor [18] Just Keep The Roses A-Blooming [18] Maori Love [21] 1919

Alhambra: Spanish One StepDixie Lullaby Feeding the Kitty: Ragtime One-Step Mother's Love and Kisses Fancies: Novelette Hawaiian Sunset: Waltzes Memoirs Water Wagon Blues Javanola: Oriental Fox-Trot Stop It!: Fox-Trot A Little Later On [18] Rose of Burgundy [18] Tokio [18] Boodiewah [22,23] Four Roses [24] 1920

Dust 'em Off: RagAsa's Toddy: One-Step Bohunkus: Novelty One-Step Umpah! Umpah! One-Step Oddity When You Made My Dreams Come True Over The Rockies (Down Frisco Way) [3] I've Been Living in the Land of Sunshine [17] Crystal Ball [18] Give My Love to Dixie [18] You've Been A Dear Old Pal (Mother of Mine) [18,25] Two Lips are Waiting in Tulip Time [25] 1921

Hop Scotch: Fox-TrotWild Oats: One-Step Torrid Dora (Toreador) The Faun: Danse Almond Eyes: Fox-Trot Asia Minor Across the Hot Sands: March Shivaree: One-Step Squares and Compass: March Put and Take: One-Step Love Lessons: Waltz Let's Take a Trip Back to Dixie [11] Love Me a Little While [26] 1922

Burglar Blues: Eccentrique Fox-TrotGhost Walk: Eccentric Novelty The Faun (Danse) Carnival Revels Dance Love and Laughter: Novelette Broken China: Oriental Novelty March of the Walking Dolls Potato-bug Parade: An Aroostook Episode You Will Never Find Tomorrow if You Haven't Found Today [27] 1923

Piano SaladDoll Days: Novelette High Brows March The New Russian Rag Morning Kisses Waltz Dixie [27] If Luck Ever Comes My Way [27] I'm Feeling Better [27] A Night In India: Suite Twilight in Reverie The Fakirs Dance of the Flower Girls By the Temple of Siva March of the Brahman Priests 1924

The American Broadcast MarchSlumber Song Spooks: Eccentric Novelty Puddle Ducks: March Grotesque Dance of the Satyrs Summer Furs: Paraphrase of the Scarf Dance Cortege of the Cyclops Mountain Laurel Waltz [17,28] 1925

The Days Gone ByChromatic Capers Dance of the Maniacs Blues You Can't Whistle Away [29] She Said You'll Forget, But He Cares [29] Dementia Americana: Suite Static and Code Hop House Blues Owl On The Organ Savannah Sunset 1926

The Lion Tamer: Galop"Old Ironsides": March Patrol Of The Pelicans Power and Glory: Processional March 1927

Procrastination RagPiano Sauce The Tippler: Eccentric March Cubistic Rag Lindy: Youth With The Heart Of Gold [30] I'm Silly Over You< [31] 1928

Potato-Bug ParadeBlue Egypt: Photoplay Music 1929

Snuggle PupAny Place Where Mother is, is Home Sweet Home to Me [32] Twilight Dreams [32] Lonesome Sweetie [33] 1930

Old Ireland, Land of the Free [34]1933

We are March, March, Marching Along [35]1942

Uncle Sam Goes to Town (Mow 'em Down,Mow 'em Down, Mow 'em Down) My Man in Uniform [36]

1. as Leo Gordon

2. w/Louis C. Snyder 3. w/Jack Yellen 4. w/Carl J. Balliett 5. w/Phil Voltz 6. w/Lucius Pratt 7. w/W.L. Beardsly 8. w/Harry Carroll 9. w/W.R. Williams 10. w/Jack Mahoney 11. w/H.C. Weasner 12. w/Richard A. Whiting 13. w/ Gus Kahn 14. w/Foster M. Lane 15. w/Thomas S. Allen 16. w/J. Will Callahan 17. w/Irving Crocker 18. w/Robert Levenson 19. w/Bob Wyman 20. w/A.J. Weidt 21. w/Treve Collins 22. w/W. Max Davis 23. w/Eddie Elliot 24. w/Aaron Neiberg 25. w/Harold Freeman 26. w/Lena Marie Archibald 27. w/James F. Connor 28. w/R.E. Hildreth 29. w/William D. Heaton 30. w/Norman Leigh 31. w/Donald E. & Edward R. Emerson 32. w/Bessie Leeper 33. w/Edward R. Emerson 34. w/William J. Finley 35. w/Anna H. French |

A native of New York State born to Linus B. Cobb and Jeannette S. "Nettie" Mains, George L. Cobb was a versatile composer who displayed inherent musical talent at a young age. He spent most of his early years in Mexico, New York. The son of a moderately wealthy farmer, Linus started in the grocery business, but by the 1890s he was working as a merchant, real estate broker and entrepreneur. His father-in-law, William Mains, was also a rather well-off farmer, so their overall family was of some means. Linus had a hand in organizing the Mexico Electric Light, Heat and Power Company in 1890 when electricity in the home was still a fairly new concept. He was also involved with the Mexico Military Academy from 1894 to 1895 as a trustee. For a time, he even sold bicycles during the beginning of the cycling craze of the 1890s. A snippet from the Mexico Independent of April 26, 1893, reads as follows:

For a time, he even sold bicycles during the beginning of the cycling craze of the 1890s. A snippet from the Mexico Independent of April 26, 1893, reads as follows:

For a time, he even sold bicycles during the beginning of the cycling craze of the 1890s. A snippet from the Mexico Independent of April 26, 1893, reads as follows:

For a time, he even sold bicycles during the beginning of the cycling craze of the 1890s. A snippet from the Mexico Independent of April 26, 1893, reads as follows:When in Syracuse the other day we went into the store of Reuben Wood's Sons, and were much surprised to see so many bicycles of the best makes. It is really a beautiful assortment, and it is no wonder that the firm is receiving orders for machines from various parts of the State. So well pleased were we with the wheels that, although owning a very handsome tricycle, we could not help buying one of them - the Queen City. Olin Wheeler, who was with us, got himself a Falcon - a beautiful machine. Carl Ballard and George L. Cobb have each a Falcon wheel, purchased of the same firm. L. B. Cobb of this village is agent for these and other wheels sold by the above-named firm.

After his traditional schooling George, received training from the School of Harmony and Composition at Syracuse University, attending there from 1904 to perhaps 1908. While in school he had one his first compositions, Dimples, locally published, and self-published Mr. Yankee, both at age 19. The following year Cobb started releasing pieces under the imprint of the H.C. Weasner & Company in Buffalo. One of them, Fleetfoot, was evidently a very good seller for the firm, and by 1907 Weasner claimed that over 100,000 copies were sold, a very high number for an instrumental by an unknown writer, so questionable at best.

The first mention of Cobb in the news was located in the Buffalo Morning Express on January 20, 1907, mentioning another publisher with which he would have a long relationship.

The Express has received a march and two-step, 'Western Life,' by George L. Cobb, published by Charles I. Davis, Detroit, Mich. It has been featured by Sousa's Band and it is sure to make a hit, for it has all the elements of success - pretty melodies, good harmonies and irresistible swing."

After graduation Cobb and his family moved to Buffalo, New York, although his intended career track there was not readily discerned. It was most likely to work as a performer and perhaps an arranger or composer. His earlier compositions had helped him win some writing contests, and one in particular would emerge in his new locale. It was a promotional rag of sorts titled Buffalo Means Business, for which he won the prize of free publication of the promotional piece. At the very least it attracted the attention of his eventual frequent lyricist Jack Yellen (1892-1991), who was a reporter with the Buffalo Courier through at least 1914 (potentially a bit longer). They wrote their first song together in short order.

It was a promotional rag of sorts titled Buffalo Means Business, for which he won the prize of free publication of the promotional piece. At the very least it attracted the attention of his eventual frequent lyricist Jack Yellen (1892-1991), who was a reporter with the Buffalo Courier through at least 1914 (potentially a bit longer). They wrote their first song together in short order.

It was a promotional rag of sorts titled Buffalo Means Business, for which he won the prize of free publication of the promotional piece. At the very least it attracted the attention of his eventual frequent lyricist Jack Yellen (1892-1991), who was a reporter with the Buffalo Courier through at least 1914 (potentially a bit longer). They wrote their first song together in short order.

It was a promotional rag of sorts titled Buffalo Means Business, for which he won the prize of free publication of the promotional piece. At the very least it attracted the attention of his eventual frequent lyricist Jack Yellen (1892-1991), who was a reporter with the Buffalo Courier through at least 1914 (potentially a bit longer). They wrote their first song together in short order.The subsequent submission of Cobb's Rubber Plant Rag to Walter Jacobs Publishers of Boston garnered him visibility and significant exposure in the East. Cobb would end up spending several fruitful years working with and for Jacobs. His earliest rags saw moderate success and distribution, and George started to compose pieces much more intricate in nature. Jacobs had hoped he had an exclusive arrangement with Cobb for his instrumental compositions, but later found out otherwise. A number of these compositions were released in packets in the early teens and beyond as orchestrations arranged for bands or movie theater ensembles.

As per a Music Trade Review notice from March 12, 1910, this practice was clearly already in process. Concerning an announcement by Jacobs of the premiere of his new magazine, Orchestra Monthly, they noted that:

This [publication] is to be to the orchestra what his 'Cadenza' is to the banjo, mandolin and guitar fraternity. In this number [75,000 copies] is a new instrumental piece, 'The Aggravation Rag,' by George L. Cobb, composer of the popular 'Rubber Plant Rag.' This is given on orchestra-size plates for ten pieces and a similar new selection will be made a feature each month. These selections will not be printed or published in any other form and can be had only in the Orchestra Monthly.

Despite this proclamation, both pieces did appear as piano solos in short order.

For the 1910 census (where the family name was erroneously enumerated as Coff), George was living in Buffalo with his parents and his maternal grandmother. He was listed as a composer of music and the occupation for Linus appears to be mines or miner, so he may have been invested in a mine of some kind as part of his real estate business. After a scant output of pieces in 1910, including one with Yellen, there was an unexplained dearth of Cobb compositions in 1911. George's sole 1911 composition with Yellen was a song of average quality. It is probable that Yellen was in Michigan by this time for further schooling. However, the output increased substantially in 1912. It is unclear what else George was doing for income, but living with his parents obviously eased that burden considerably.

After a scant output of pieces in 1910, including one with Yellen, there was an unexplained dearth of Cobb compositions in 1911. George's sole 1911 composition with Yellen was a song of average quality. It is probable that Yellen was in Michigan by this time for further schooling. However, the output increased substantially in 1912. It is unclear what else George was doing for income, but living with his parents obviously eased that burden considerably.

After a scant output of pieces in 1910, including one with Yellen, there was an unexplained dearth of Cobb compositions in 1911. George's sole 1911 composition with Yellen was a song of average quality. It is probable that Yellen was in Michigan by this time for further schooling. However, the output increased substantially in 1912. It is unclear what else George was doing for income, but living with his parents obviously eased that burden considerably.

After a scant output of pieces in 1910, including one with Yellen, there was an unexplained dearth of Cobb compositions in 1911. George's sole 1911 composition with Yellen was a song of average quality. It is probable that Yellen was in Michigan by this time for further schooling. However, the output increased substantially in 1912. It is unclear what else George was doing for income, but living with his parents obviously eased that burden considerably.Cobb was briefly married to Clara (or Claire) Bailey, the estimated marriage and subsequent divorce having occurred between mid-1912 and mid-1915. A Clara Bailey of upstate New York was found in census records, and was likely his first wife. She was shown to be single in 1910 and divorced in 1920, and was in the right area and time frame to have encountered Cobb.

Sometimes overlooked by pianists are the songs that Cobb wrote or co-wrote. They had the undercurrent of piano-based ragtime with the salability of popular songs. He also had some success at writing his own lyrics from time to time. Just the same, upon his graduation in 1913 from the University of Michigan, Jack Yellen came back to Buffalo to continue to write songs with the composer he so admired. Among the most frequently performed Cobb and Yellen songs are a number of "Dixie" tunes. These include Listen to That Dixie Band, See Dixie First and their first major tune about the storied south, All Aboard for Dixie Land.

As recounted by performer/historian Frederick Hodges, the pair had trouble selling the song during the difficult year of 1913 when publishers were fighting with discount houses, performers, and even composers wanting some equity. So, they ended up selling the piece to the smaller publishing house of J. Fred Helf. In October a new show by composers Rudolf Friml and Otto Hauerbach titled High Jinks was receiving only tepid response in its trial run in upstate New York. Producer Arthur Hammerstein was looking for something to save it from total failure, making adjustments at every theater it was shown in. One of the problems was that there were no real "hit" tunes in the score for star Elizabeth Murray, a long-established energetic "coon shouter," to put over on the audience. In Chicago, Hammerstein decided to interpolate All Aboard for Dixie Land into the show, creating both a hit show and a hit song in an instant. By the time it got to Broadway in December 1913, the entire nature of the production had changed due to that piece. It helped codify Cobb and Yellen as very credible tunesmiths.

In Chicago, Hammerstein decided to interpolate All Aboard for Dixie Land into the show, creating both a hit show and a hit song in an instant. By the time it got to Broadway in December 1913, the entire nature of the production had changed due to that piece. It helped codify Cobb and Yellen as very credible tunesmiths.

In Chicago, Hammerstein decided to interpolate All Aboard for Dixie Land into the show, creating both a hit show and a hit song in an instant. By the time it got to Broadway in December 1913, the entire nature of the production had changed due to that piece. It helped codify Cobb and Yellen as very credible tunesmiths.

In Chicago, Hammerstein decided to interpolate All Aboard for Dixie Land into the show, creating both a hit show and a hit song in an instant. By the time it got to Broadway in December 1913, the entire nature of the production had changed due to that piece. It helped codify Cobb and Yellen as very credible tunesmiths.Helf could not handle the sudden demand for the Cobb/Yellen tune, so All Aboard for Dixie Land and some others from the show were sold to the dominant firm of Jerome H. Remick for around $2,500. The song became a greater hit in 1914. The play, however, barely made it into the spring. Ironically it was silent film that saved the play and made the song an even bigger hit. The decision to include two of the song numbers, albeit without sound, in a Mabel Normand film titled Our Mutual Girl, benefitted both the play and composers, and by April it was back on track. Everybody involved with the show, including the composers, made out very well in the end. Miss Murray continued to favor Cobb and Yellen pieces for some time.

Another major Dixie song, Are You From Dixie?, became an early Al Jolson hit. It has since been frequently quoted in movies and for many years, thanks to composer Carl Stalling, had a heavy presence in Warner Brothers cartoons. One of their biggest successes was the now ubiquitous Alabama Jubilee, still a favorite of ragtime pianists and banjo players everywhere. The cover once again featured Murray, and was a blessing for her. After a contentious battle concerning issues with High Jinks she was enjoined from performing All Aboard for Dixie Land in public. Alabama Jubilee became an enormous hit for her and the composers in the fall of 1915. Yellen's down-home lyrics certainly contributed to the popularity of these songs, as they fit to Cobb's melodies so well. From that point on many of the pair's collective works became million-sellers in both printed and recorded form. The 1915 New York State census, taken earlier in the year, showed George in Buffalo, single once again and residing with his parents, listed as a composer of music. Linus listed his occupation at that time as "Mining Promoter."

Alabama Jubilee became an enormous hit for her and the composers in the fall of 1915. Yellen's down-home lyrics certainly contributed to the popularity of these songs, as they fit to Cobb's melodies so well. From that point on many of the pair's collective works became million-sellers in both printed and recorded form. The 1915 New York State census, taken earlier in the year, showed George in Buffalo, single once again and residing with his parents, listed as a composer of music. Linus listed his occupation at that time as "Mining Promoter."

Alabama Jubilee became an enormous hit for her and the composers in the fall of 1915. Yellen's down-home lyrics certainly contributed to the popularity of these songs, as they fit to Cobb's melodies so well. From that point on many of the pair's collective works became million-sellers in both printed and recorded form. The 1915 New York State census, taken earlier in the year, showed George in Buffalo, single once again and residing with his parents, listed as a composer of music. Linus listed his occupation at that time as "Mining Promoter."

Alabama Jubilee became an enormous hit for her and the composers in the fall of 1915. Yellen's down-home lyrics certainly contributed to the popularity of these songs, as they fit to Cobb's melodies so well. From that point on many of the pair's collective works became million-sellers in both printed and recorded form. The 1915 New York State census, taken earlier in the year, showed George in Buffalo, single once again and residing with his parents, listed as a composer of music. Linus listed his occupation at that time as "Mining Promoter."Noting that Cobb was submitting his works to many different New York firms, and even to Will Rossiter in Chicago who had taken on his hit Just For To-Night, Jacobs finally thought to offer Cobb steady work as a staff arranger, which George soon accepted. As announced in The Music Trade Review of September 30, 1916, "Walter Jacobs, whose establishment in Bosworth street, Boston, is a busy hive of industry, has now associated with him two able men who will prove without doubt of the most valuable assistance in his work. One of these is George L. Cobb, of Buffalo, who is widely known as a composer, and, who besides writing popular compositions, will do more or less traveling. Mr. Cobb is best known for his song, 'Are You from Dixie?' which is having an enormous vogue. Another of the Dixie numbers is entitled 'See Dixie First,' and this is being put out by Jacobs." (The other staff member mentioned was the largely unknown banjoist C.V. Butterman.) However, to Jacob's regret, he did not specify exclusivity as a composer for the firm in Cobb's contract, so his employee was free to shop around for the best deal for his songs and instrumentals. Cobb pieces still appeared under the Rossiter imprint as well.

Cobb moved to Cambridge, Massachusetts in late 1916 to facilitate this new position, bringing his parents with him. On November 20, 1916 he married his second wife, Mary Belle Barr, formerly of Buffalo and also Saxton, Pennsylvania, in Boston. As reported in The Music Trade Review of December 9, 1916: "The ceremony was performed at the parsonage of the Union Congregational Church by Rev. Ernest G. Guthrie, the pastor. Mr. Cobb and his wife are making their home in Allston, and will be at home to their friends after January 1."

As reported in The Music Trade Review of December 9, 1916: "The ceremony was performed at the parsonage of the Union Congregational Church by Rev. Ernest G. Guthrie, the pastor. Mr. Cobb and his wife are making their home in Allston, and will be at home to their friends after January 1."

As reported in The Music Trade Review of December 9, 1916: "The ceremony was performed at the parsonage of the Union Congregational Church by Rev. Ernest G. Guthrie, the pastor. Mr. Cobb and his wife are making their home in Allston, and will be at home to their friends after January 1."

As reported in The Music Trade Review of December 9, 1916: "The ceremony was performed at the parsonage of the Union Congregational Church by Rev. Ernest G. Guthrie, the pastor. Mr. Cobb and his wife are making their home in Allston, and will be at home to their friends after January 1."One hit that Jacobs was able to get his hands on was the 1917 patriotic war booster song The Battle Song of Liberty by Cobb and Yellen. Cleverly adapted from F.E. Bigelow's famous march Our Director, it was one of many tunes that managed a swell of popularity until George M. Cohan's Over There swept the world. He also spent some time traveling in 1916 promoting his employer, with sightings in Chicago and Michigan. While still selling his tunes to Jacobs and other publishers, George was assigned to write for the Jacobs' company newest music trade magazine, The Tuneful Yankee. He held this post for a few years starting in January of 1917. Cobb's role there was as a music critic or commentator on compositions submitted by amateurs, which he handled quite deftly, but also with brutal honesty at times. In 1918 the magazine was recast as Melody, and his column was called "Just Between You and Me," which ironically was often a not-so-private venue for the occasional evisceration of amateur composers. If he thought something submitted to the magazine for analysis was tripe, he had little trouble saying so.

Many of Cobb's later compositions also appeared only in the magazine, and not as separate sheet music publications. There is speculation that pieces attributed to other composers might be by Cobb, with Leo Gordon being his primary pseudonym, and that some of the compositions from this time were simply not at the same level as his more notable sheet music pieces because of the rigors of contribution and editing deadlines. Among those alternate names were Bernard Fenton, Tod Hamilton, Elizabeth Strong and Allen Taylor.

Even though he worked for Jacobs during the teens and later, Cobb still published where he could get the best deals and distribution. One of his overall biggest successes, and personal favorites, was his Russian Rag, based on Sergei Rachmaninoff's famous C# Minor Prelude, released by Will Rossiter of Chicago. The esteemed contemporary classical composer was reportedly nonplussed by this adaptation, but it did provide him good exposure. Russian Rag was first featured in Chicago at the Majestic Theater by Mademoiselle Rhea who was a costume dancer in vaudeville. Even though she was featured on some of the covers of the piece as well, her endorsement was less viable, based on reviews of her act. One reviewer noted that her accompanying violinist and pianist were only average which detracted from her dancing ability. So, there was a slow start for sales of Russian Rag until 1919 when it was recorded and endorsed by the famous Six Brown Brothers ragtime saxophone sextet. They were also shown on the cover of subsequent editions of the piece. As quoted below, the group's leader said that Rachmaninoff actually enjoyed their rendition. The rag ultimately became so popular that a few years later it was re-written as The New Russian Rag to reflect Cobb's more advanced Novelty Ragtime compositional style.

Another 1918 piece of Cobb's that the Brown Brothers recorded created a stir in musical circles in the United States and nearly incited an international incident. Among those American critics was dissenter Gregor M. Mazer who in the September 1920 issue Melody magazine said: "[It is] disgraceful... the way beautiful music is being converted into vulgar, impossible jazz... When Grieg's immortal 'Peer Gynt' is printed on a program 'Peter Gink' it is time for all music lovers to rebel against this outrageous profanity." Further criticism came from Grieg's homeland as reported in the November 24, 1920, New York Tribune:

Peer Gynt Shimmie Makes Norway Shiver With Anger

Protest Sent to Washington Against Turning Grieg's Classic Into Jazz Music on Phonograph Record; "a Shame," Declares Enrico Caruso

Protest Sent to Washington Against Turning Grieg's Classic Into Jazz Music on Phonograph Record; "a Shame," Declares Enrico Caruso

Norway in particular and Scandinavian music lovers in general, are shocked to find that Edvard Hagerup Grieg's famous "Peer Gynt Suite" has been jazzed and is being circulated in its corrupted form on phonograph records. Representatives of high Norwegian culture, who have a sympathetic feeling for Grieg's austere compositions, have forwarded to the government authorities at Washington a memorial protesting against "such a desecration of genius."

Representatives of high Norwegian culture, who have a sympathetic feeling for Grieg's austere compositions, have forwarded to the government authorities at Washington a memorial protesting against "such a desecration of genius."

Representatives of high Norwegian culture, who have a sympathetic feeling for Grieg's austere compositions, have forwarded to the government authorities at Washington a memorial protesting against "such a desecration of genius."

Representatives of high Norwegian culture, who have a sympathetic feeling for Grieg's austere compositions, have forwarded to the government authorities at Washington a memorial protesting against "such a desecration of genius."Composers, singers and conductors in New York who expressed their views yesterday are inclined to think that Norway is right. Tom Brown, however, who transformed Shubert's "Serenade" and Rachmannioff's "Prelude" [Cobb's Russian Rag] into the raggiest of rags and whose company played the jazzed "Suite" for records, has a different opinion.

"Sergei Rachmaninoff heard us play the adaptation of his work." he said, "and liked it, considering this a method of popularizing real music. We play such adaptations to attract attention and we find that the public takes to adaptations better because familiar melodies appeal. That's reason enough."

Mme. Marie Sundelius, Enrico Caruso and Albert Spalding, an American violinist, were of the opinion that Norway has just cause for indignation. Norway, it seems, learned of the desecration when an assortment of American talking machine records reached that country recently. One record, entitled "Peter Gink." composed by George L. Cobb and played by the Six Brown Brothers, was heard by Norwegian music lovers. Shocked beyond words, they began preparation of the memorial and it was forwarded with haste to Washington.

Mme. Sundelius, soloist of the Metropolitan Opera Company, said that she had been reading of the "sacrilege" in Swedish papers. "A composer does not like people to use his melodies in that way," she said, "and it was not a nice thing to make ragtime out of Grieg. Surely there is enough popular music to adapt without going to the classics."

Caruso, whose voice is recorded by the company which first put out the Grieg ragtime, said: "There ought to be a law against it. It is a shame."

"An awful shame, outrageous." was the comment of Mischa Levitski, the pianist.

Arthur Bodanzky, conductor of the National Symphony Orchestra and also with the Metropolitan Opera Company, said he had no objection to jazz, but the jazz makers should at least be original about it and have enough invention to get along without robbing the classics.

Mr. Spalding, as an American violinist, expressed the opinion that the public, interested in good music, and also those jealous of the country's good name as to culture, should see to it that good music is not twisted into ragtime.

"There is an element of interest in ragtime," he said, "from a rhythmic standpoint, but certainly our fine melodies should not be dished out in that form. There should be legislation to prevent it."

It appears that Cobb, who surprisingly seems to have received very little blame, most certainly got away with the outrage, and since plagiarism was not at issue, no Federal laws were passed against such parodies. He followed Peter Gink by editing and publishing The Blacksmith Rag, a parody on the Anvil Chorus from Giuseppe Verdi's Il Trovatore, and a clever take on the Toreador Song from Georges Bizet's opera Carmen.

He followed Peter Gink by editing and publishing The Blacksmith Rag, a parody on the Anvil Chorus from Giuseppe Verdi's Il Trovatore, and a clever take on the Toreador Song from Georges Bizet's opera Carmen.

He followed Peter Gink by editing and publishing The Blacksmith Rag, a parody on the Anvil Chorus from Giuseppe Verdi's Il Trovatore, and a clever take on the Toreador Song from Georges Bizet's opera Carmen.

He followed Peter Gink by editing and publishing The Blacksmith Rag, a parody on the Anvil Chorus from Giuseppe Verdi's Il Trovatore, and a clever take on the Toreador Song from Georges Bizet's opera Carmen.As of the 1920 census, George was living in Cambridge, Massachusetts, with his wife and mother, with his father Linus listed as the head of the household. George was listed as a musical composer with his "own company," although the nature of that assertion is unclear. Linus was listed as a broker with his own office. Cobb continued his acerbic writings in Melody. Throughout the 1920s he also composed a number of great novelties both within and separate from Melody, such as Piano Salad, Snuggle Pup and Chromatic Capers. Given that only Cobb and British-born composer Richard E. Hildreth were permanent members of Jacobs' writing staff, it is likely that many of the pieces released in Melody and even as separate sheets were composed by one of them under a variety of pseudonyms. However, pinpointing which of these were used by Cobb would be a daunting forensic task, so other than the Leo Gordon pieces they are not included in his song list. He also advertised from time to time as a free-lance creator of melodies composed for lyrics, using his home address as this was evidently a moonlighting song-poem operation.

Linus Cobb died in Boston on January 24, 1925, and was buried in Mexico, New York. At some point in the late 1920s Cobb divorced Mary and moved to Somerville, Massachusetts, a suburb of Boston. He subsequently married Clara E. Dewey in a ceremony in Manchester, New Hampshire, on February 25, 1929, but that appears to have lasted only a year or so. The 1930 census taken in nearby Brookline, Massachusetts, showed him as divorced and working as a publishing salesman, as he seems to have mostly retired from music composition by this time. It also showed that his mother Jeannette was still living with him. From that point on little is known of his life in retirement in Brookline. It appears, however, that he finally left the music business nearly altogether.

As of the 1940 enumeration George was lodging with Mabel Hayward and her son Clyde in Brookline, Massachusetts, shown as a salesman for local Chamber of Commerce memberships. Cobb's 1942 draft registration, perhaps the final official document of his life, had him still living in Brookline, continuing his work for the Chamber of Commerce, with his "person who will always know you" reference being one Evelyn F. Eaton (b.1894) in nearby Cambridge. The nature of their relationship was not discerned through research or extant records. Cobb's final two compositions, written after an absence of nearly a decade, appeared in 1942, the year he joined ASCAP. Spending his last days in a convalescent home in Brookline, Massachusetts, George Linus Cobb died of coronary thrombosis complicated by a duodenal ulcer at age 56 on Christmas Day 1942 [December 27 has also been cited]. Curiously, his first wife Claire (albeit possibly intended as his third wife Clara) was cited on his death certificate, which does show him as divorced. His gravesite is in his hometown of Mexico, New York.

The instrumental compositions of George L. Cobb, which span over two decades, have generally been put into three categories of development. His earliest pieces are thought to be in the Popular vein, which was in part written as something for the sake of getting sold, although with a bit more aplomb in Cobb's case. By the mid-1910s George was getting much more adventurous and clever, so given the chord changes he was using and the complex trios, the rags and intermezzos from this period fall into the advanced ragtime category. Finally, he had little trouble adapting to the novelty style invented or adopted by many of his younger peers. While his novelty works never sold in large numbers, they were still very worthy entries into the collective. The strength of his many songs lies in memorably simple melodies with chord progressions that enhanced, but did not get in the way of those melodies.

Many thanks to Canadian Ragtime historian Ted Tjaden who provided some of the information here to supplement my research, as well as rediscovery of many of the previously unknown Cobb pieces. Visit his site at www.ragtimepiano.ca. Special acknowledgement goes to the brilliant pianist and Cobb historian Frederick Hodges who managed to fill in some of the important details about Cobb's career and his parents. Thanks also to retired librarian Marilyn McClure who sent Ted and myself a copy of Cobb's second marriage license, and gave us the name of Claire (likely Clara) from his death certificate as his wife. His marriage certificate to Mary shows as his second marriage and her first, putting Claire in that time between 1912 and 1916 when he remarried.