|

Harry James Lincoln (April 13, 1878 to April 19, 1937) | |

Compositions Compositions | |

|

1900

The Midnight Fire AlarmThe Conservatory March and Two Step 1901

The Police PatrolPride of the Century Repasz Band [1] (1901/1904) 1902

The Circus GirlThe Band Master A Soldier's Last Farewell [2] 1903

Vallamont (Valley and Mountain)1904

The Buffalo FlyerThe Fire Master The Fire Worshippers McKinley's Memorial March The New York Subway (or Rapid Transit) Salute to America Heaven's Artillery 1905

Tango QueenThe Palm Limited How to Look at Money When You're Broke The False Alarm Just at the Break of Day The Peace Conference The Rifle Range A Southern Dream: Waltzes Zenith: Intermezzo Spirit of Freedom [3] 1906

AuroraSounds From the Orient Sounds From the Tropics Baldwin Commandery Whispering Waves: Waltzes The Merry Makers: March Nuptial Waltzes Observatory: March and Two Step The Tournament Tri-State: March and Two Step Susquehanna: March Peerless King [3] The Joker [3] 1907

Nippono: IntermezzoEvening Thoughts: Waltzes The Crater: March and Two Step Orpheus: Waltzes The Lost Phase: Waltzes Vesuvius: March Two Step Four Aces [3] The Four Deuces [3] The Four Jacks [3] Four Kings [3] Four Queens [3] Four of a Kind [3] Excuse Me, But Isn't Your Name Johnson? [4] My Southern Home [5] 1908

The Circuit: March and Two StepA Jolly Sailor: March The Focus: March The Flash-Light: March The Pacifier: March Empire Express: March and Two Step Babbling Brook Which Way Did My Mamma Go? The 12th Regiment (N.G.P.) Alameda: Waltzes Our Victorious Nation The Flowers of the Forest A Full Hand [3] A Royal Flush [3] Our Sammies [6] The Fight is On [6] 1909

Angels of the Night: ReverieRag-Bag Rag Honest Confession: Morceau Characteristic A Dream of the South: Waltzes Moss Rose: Morceau Characteristic Playmates: March and Two Step Toro: Spanish Serenade Alpine Rose: A Flower Song Pony Maid: Romanza Fire Drill Poverty Rag Garden of Dreams King of the Forest [3] Pony Maid (Song) [7] Only a Dream of You [7] Thunder and Lightning [7] 1910

Halley's CometFairies of Dawn My Western Rose (Inst) Someday Someone Will Whisper I Love You The Pioneer Limited Sunset Limited Homeland Waltzes Midnight Special Day Dreams Only You [8] My Western Rose (Song)Only You [9] 1911

Golden WeddingBees-Wax Rag Dixie - A Rag Caprice Capitol City March I-X-L - March Two Step Schoolmates Angel Kisses Trinity Chimes Frolic of the Imps Sunbeams and Shadows None But You: Meditation None But You: Song King of Hearts [3] Jack of Spades [3] 1912

Sunlight and LoveRipples of the Allegheny Garden of Sunshine Inspiration Reverie Dance of the Fairies Roman Races The Wolverine: March Roseland: Three Step Bo-Peep: March Tears and Smiles Fidelity [3] Kings and Queens [3] 1913

Checkers RagTwilight Echoes The Tempest Go the Other Way Old Hickory Sereno Warbles at Eve Ice King Scotland Bells - Waltzes Showers of Spring Bang Up - Two Step Tallalula Band Uncle Silas [3] Going Some [7] Fairies' Fancy: Morceau Characteristic [7] Garden of Lilies: Waltzes [7] Springtime - Gavotte [7] Ferns and Flowers [7] The Red Ribbon Waltzes [7] When I First Met You [7] The Puritan [7] Garden of Beauty Waltzes [7] Moonlight: Three Step [7] 1914

Black Diamond RagLove's Caresses High Speed Frolic of the Waves A Hummer Little Princess In a Summer Garden Angel Whispers A Little More Pepper The Steeple Chase: March Blaze of Honor Still Alarm Circus Life Sunburst: Reverie-Serenade Dreaming at Twilight: Waltzes Ace of Diamonds [3] If Time Would Tell [7] It Cannot Be [7] A Girl I Know [7] Just for the Love of You [7] Vacation Waltzes [7] A Woman Without a Heart [7] The Story of the Rose [7] That's What I'd Do for You [10] That Aero Rag [11] My Southern Home: Medley Waltz [12] 1915

December Morn (Inst)Dreaming at Twilight: Song Goblins Hand of Friendship Pioneer March and Two Step Vesper Chimes Crossing the Bar Rose Garden United Musician March Mrs. Maximum Neutral March |

1915 (Cont.)

Old ReliableAfter-glow: Reverie Sounds of the Tropics: Waltzes Arbitration [3] December Morn (Song) [7] Hearts of Promises: Waltzes [7] Going Some [7] Grace and Beauty Waltzes [7] Dove of Peace [7] 1916

Rosetime: ReverieOft-Times Recess After-Glow (Mother's Old-Time Lullaby) [13] 1917

Glory of Womanhood: WaltzThe New Liberty: March Our Soldiers of '17 [14] 1918

In the Moonlight ?Love's Idle Hours ? Shine On, O Beautiful Star Silent Confession O! Beautiful Star Sliding Sid [3] Marshal Haig [3] 1919

Gee Whiz!The Honeymoon Rose of Heaven For All and Forever The Great American (Theodore Roosevelt) [2] 1920

The Gallant HeroTo the Rescue Pepper Up A Castle in Dreamland [15] Mary, I Love You So [16] Repasz Band (Song) [17] Vote For the Right Man [18,19] 1921

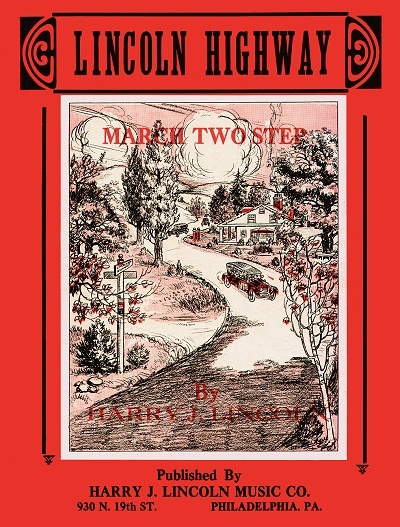

Mounted PoliceThe American Princess Lincoln Highway Electric Current Noisy Neighbors She's a Wonderful Girl [18,20] Rosie, I Love You [18,20] Monkey Life [18,21] Sweet Wyoming Rose [18,22] Don't Take the Stinger from the Bee [18,23] 50-50 (Fifty-Fifty) [18,24] 1922

Silent ThoughtsStriking Fire The Shades of Voteresses [18,25] 1923

American EmblemListening In How Could I Leave You Dad? Susquehanna Trail March Girls of America Keystone Division [3] The Comedy King [3] Kill-Kare [3] Flowers of the Orient [7] Emblem of Peace K (Sacred Song) [18,26] Boycott Song [18,27] Dreaming of Old Kentucky [18,28] I Can't Forget [29] Loving Blues [18,30] So Long Kitty [18,31] She's That New Mamma o'Mine [18,32] There's No Excuse Left Here for You [18,33] Corn Beef and Cabbage [18,34] Every Day and Every Way [18,35] Honey Moon (Waltz) [18,36] We Are the Ladies of the Ku Klux Klan [18,37] 1924

Fringe of FashionThe Glacier: March and Two Step Belle of the Season Harvesting [18,38] Some Little Something [18,39] Tea Pot Dome Blues [18,40] Fire Up the Kettle on Tea Pot Dome [18,41] Save Me the Curls of the Bobbed Haired Girls [18,41] You Had Better Be Ready That Morn When Gabriel Toots His Golden Horn [18,42] Since I Fell for You [18,43] 1925

Peace On EarthSouthern Cross Soldiers of Peace Peerless Rider National Federation March The Captain West Virginia [18,44] Texas and Her Flag [18,45] 1926

The Letter CarriersThe Radiant Bride For the State of Florida [18,46] Florida has a Welcome For You [47] Dreamy Swanee Lullaby [48] 1927

The Gallant RiderThe Idolizer 1928

Sky BluesMark Time Dancing Clowns Canonade Top Notch True Blue [3] Kick Off [3] Hickory Nuts Rag [3] O Prince of My Dreams [18,49] We - March/One Step [50] Triumphant Lindbergh [50] 1929

Repasz on ParadeOh! How I Hated to Lose You [18,34] Some Day Far Away in California [18,51] The Great Smoky Mountain National Park [18,52] 1931

Way Down East: MarchI Couldn't Love Without an Inspiration [18,53] The Lullaby (Cradle Song) [18,54] Me and My Radio [18,55] 1935

Tell Me Why [56]Social Justice [56] 1936

Just South'ard of the Line [18,57]

1. arr. for Charles C. Sweeley

2. w/Charles A. Mulliner 3. as Abe Losch 4. w/William Hauser 5. w/Reverend James A. Patton 6. as or w/Carl D. Vandersloot 7. as or w/Carl Loveland 8. w/Reba Vandersloot 9. w/Federick Vandersloot 10. w/Ida Vandersloot 11. w/Warner Crosby 12. w/P. Douglas Bird 13. w/James Royce Shannon 14. w/Thomas D. Casale 15. w/F.B. Lovett 16. w/H.A. Tilton 17. w/Ray Sherwood 18. as Harry Jay 19. w/Emma A. Parker 20. w/A.J. Stevens 21. w/W. Tully 22. w/J.M. Cox 23. w/J.P. Cooper 24. w/E. Bennett 25. w/J.H.B. Scheuyeaulle 26. w/Thomas E. Cupper 27. w/Andrew Bowers 28. w/Orla Cure 29. w/Milton W. Shrode 30. w/Harry A. Van Alstyne 31. w/William G. 32. w/Louis Bloom 33. w/Stephen Browning 34. w/J. Elliot Jones 35. w/E.A. Grimes 36. w/J.W. Steele 37. w/Roy Metz 38. w/Elmore Everett 39. w/F.F. 40. w/Frances Bradley 41. w/John Storm 42. w/A.C.H. 43. w/G.B. Rayburn 44. w/Thomas J. Honaker 45. w/Virginia Pickett Bonner 46. w/Cleveland Scott 47. w/George A. Kalar 48. w/George C. Pennington 49. w/K.M. McGregor 50. w/Ruth Hoyt 51. w/Olive Marjory E. Welcolm 52. w/Claudius Meade Capps 53. w/E.F. Roberts 54. w/A.C. Templeton 55. w/M. Jennings 56. w/Glenn A. Dewey 57. w/Louise Poage |

Harry J. Lincoln creates a bit of a conundrum for researchers for a variety of reasons. The parentage of many of his pieces is uncertain since they were published under the names of both contrived and existing composers, and given the vast quantity of his works there is surprisingly little about his life outside the publishing and writing arenas. Even though he was one of the lesser-known composers of the ragtime era, his works still sold briskly, in part due to the creative Walter J. Dittmar covers often found on his Vandersloot-published works,  and the sheer quantity of his output permeates sheet music piles around North America and other parts of the world. He was also not without some level of controversy, although not intentionally.

and the sheer quantity of his output permeates sheet music piles around North America and other parts of the world. He was also not without some level of controversy, although not intentionally.

and the sheer quantity of his output permeates sheet music piles around North America and other parts of the world. He was also not without some level of controversy, although not intentionally.

and the sheer quantity of his output permeates sheet music piles around North America and other parts of the world. He was also not without some level of controversy, although not intentionally.Harry was born to coal miner Conrad L. Lincoln and his wife Margaret Losch, both Pennsylvania natives, in Shamokin, Pennsylvania (although probably not in a log cabin like the other Lincoln), and spent his entire life based in the state. He was the youngest of five children, including Jacob (1867), John (1869), Ida (1871) and George (1873). While little is known of his education, musically or otherwise, he did become a choirmaster and organist in Williamsport at the First Church of Christ. He also became an associate conductor for the Williamsport Symphony, vaguely in the area of 1900 or later.

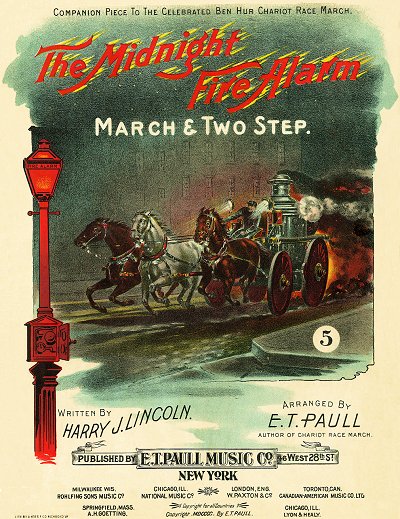

Harry self-published one of his first compositions in early 1900, The Midnight Fire Alarm, which was subsequently bought and rearranged by famed march publisher Edward Taylor Paull. It ultimately became one of the best known pieces in the Paull catalog. (To quash a common myth, Paull never covered Lincoln's identity as composer, and all editions properly credit him.) Harry was listed as a music teacher in the 1900 census, and had married Miss Lottie May Bovec in 1898.

When he was first established in Williamsport around 1900, Lincoln submitted a couple of pieces to local music salesman and sometime publisher Charles A. Mulliner. These included The Police Patrol (a companion to Midnight Fire Alarm), Flowers of the Forest, and the recently uncovered The Circus Girl, which may have been prompted by a musical of the same name that came out at that time. There were some later works, including songs co-written with Mulliner, released up to a decade later after Harry's reputation was better known, but likely printed with help from Harry under Mulliner's moniker, as he appears only as a music salesman in the 1910 census. They may also have been printed by Charles' brother in law who Lincoln later worked with. Harry also arranged or perhaps co-wrote a few pieces with Mulliner's music teacher wife, Ida (Furman) Mulliner as I. Furman Mulliner. He also self-publihed a couple of marches, although with very limited distribution, making them exceedingly rare today. His next most famous piece, and also reportedly the second-most played march in history, was one of the points of a controversy that exists over a century later.

|

Lincoln's side of the troublesome story is that he had written a 6/8 march piece honoring the band as early as 1896 or 1897, but had trouble selling it to a variety of publishers. After the success of Midnight Fire Alarm, plus in need of money, he was able to sell it to Mr. Sweeley who subsequently published Repasz Band under his own banner and composition credit. Having not marketed the piece very well, Sweeley let it drop. As Lincoln's situation improved he reformed his publishing company and took back Repasz Band. However, either out of respect for Sweeley or because the parentage had been established through copyright, he left Sweeley's name on the composition. After Lincoln dissolved his small publishing firm in 1903 he was hired on at Vandersloot Music in 1904 after Vandersloot published Heaven's Artillery. Owner Frederick W. Vandersloot also bought the Lincoln copyrights, and wanted to meet the composer of the marvelous Repasz Band march which he had republished in 1904. At this point Lincoln revealed it was his own, but they continued to publish it with Sweeley's name until the mid-1910s. When the copyright was renewed in 1929 Lincoln reclaimed the piece as his own, which was allegedly reinforced by a sworn statement from Sweeley himself, a statement that currently resides in the Library of Congress.

At this point Lincoln revealed it was his own, but they continued to publish it with Sweeley's name until the mid-1910s. When the copyright was renewed in 1929 Lincoln reclaimed the piece as his own, which was allegedly reinforced by a sworn statement from Sweeley himself, a statement that currently resides in the Library of Congress.

At this point Lincoln revealed it was his own, but they continued to publish it with Sweeley's name until the mid-1910s. When the copyright was renewed in 1929 Lincoln reclaimed the piece as his own, which was allegedly reinforced by a sworn statement from Sweeley himself, a statement that currently resides in the Library of Congress.

At this point Lincoln revealed it was his own, but they continued to publish it with Sweeley's name until the mid-1910s. When the copyright was renewed in 1929 Lincoln reclaimed the piece as his own, which was allegedly reinforced by a sworn statement from Sweeley himself, a statement that currently resides in the Library of Congress.Members of the Sweeley family contest the story, as well as the handwriting on the statement. Sweeley's son had the handwriting analyzed by a professional and it was ascertained to be a potential forgery. The original copyright submission clearly shows Sweeley as the composer and Lincoln as the arranger. Also, there was been some duress in terms of Lincoln's claim over the piece. Lincoln made two attempts to re-copyright it in 1929, the first being rejected. The second attempt had the alleged sworn statement backing it up.

There are points to be made for either scenario. Given Lincoln's prolific career and Sweeley's comparatively minimal output, it could seem more likely that Lincoln possibly contributed to a few more Sweeley pieces. Sweeley spent most of his adult life working with Lycoming Rubber, playing with bands on the side, but not as a full-time musician or composer. There is also the fact that Mr. Sweeley continued to have his works published by Vandersloot, which would not make sense if there were any serious contention between him and the company manager, Mr. Lincoln. A modicum of doubt must still be considered in this instance concerning authorship. Those who knew the real story are long gone. The claims of the Sweeley family need to be considered in balance with those of Lincoln, and duly respected as sincere and honest.

The author did a forensic analysis comparing Repasz Band with similar characteristic pieces by both composers. The most logical and probable conclusion that could be reached was that it was likely Sweeley's melody, but clearly arranged in Lincoln's style for both piano and band. Just as E.T. Paull's arrangement of Midnight Fire Alarm contributed to its major success, Lincoln's likely adjustments (based on other Sweeley works) to Repasz Band likely had an impact on it as well. Both men deserve credit in different ways for making the piece popular, so hopefully there is enough to go around. Coming to an absolute conclusion of full authorship is difficult to achieve when all of the known facts are considered.

Just as E.T. Paull's arrangement of Midnight Fire Alarm contributed to its major success, Lincoln's likely adjustments (based on other Sweeley works) to Repasz Band likely had an impact on it as well. Both men deserve credit in different ways for making the piece popular, so hopefully there is enough to go around. Coming to an absolute conclusion of full authorship is difficult to achieve when all of the known facts are considered.

Just as E.T. Paull's arrangement of Midnight Fire Alarm contributed to its major success, Lincoln's likely adjustments (based on other Sweeley works) to Repasz Band likely had an impact on it as well. Both men deserve credit in different ways for making the piece popular, so hopefully there is enough to go around. Coming to an absolute conclusion of full authorship is difficult to achieve when all of the known facts are considered.

Just as E.T. Paull's arrangement of Midnight Fire Alarm contributed to its major success, Lincoln's likely adjustments (based on other Sweeley works) to Repasz Band likely had an impact on it as well. Both men deserve credit in different ways for making the piece popular, so hopefully there is enough to go around. Coming to an absolute conclusion of full authorship is difficult to achieve when all of the known facts are considered.After he was established at Vandersloot, Harry became the primary (at times only) staff arranger and one of two hired composers, the other one being Frank Hoyt Losey who joined in 1909. Vandersloot's brother Carl wrote for the firm from time to time, but not consistently until the mid-1910s. In some or the registered copyrights, Lincoln claims Carl D. Vandersloot as his own pseudonym, so there is a blurry line between what Carl may have contributed and what Harry claimed.

Another such case was that of Carl Loveland. There was an Alabama-born (1891) musician of that name who was living in Chicago, Illinois in 1900, but not located again until the mid-1910s when he was working as a bandleader in Portland, Oregon, later moving to Seattle, Washington, then settling in Monterey, California. Whether Lincoln simply coincidentally used that name or the real Mr. Loveland contributed is uncertain, and evidence either way is difficult to ascertain. Loveland would have been 18 when works with that name started appearing in the Vandersloot catalog. Later copyright renewals show Carl Loveland to be a Lincoln pseudonym, but as with Sweeley there may be some question as to the authenticity of that claim.

In the years preceding 1910, while writing many marches, reveries, waltzes, and a clever "suite" of card-based pieces under his frequent pseudonym Abe Losch (derived from his mother's maiden name), Lincoln had not yet composed any authentic piano rags. He did appear to have a fascination with fire, however, as many of his marches seemed oriented towards fires and firefighting, dating back to Midnight Fire Alarm. With Losey as competition, and with the publication of rags by Charles L. Johnson, Charles Cohen and Harry A. Fischler, Lincoln started contributing a small number of syncopations. Even so, piano ragtime in general from Vandersloot was a rarity, in spite of Lincoln's output, which actually exceeded that of E.T. Paull's own compositions. (It should be noted that for some time Fischler was mistakenly considered as yet another pseudonym for Lincoln, but Fischler's identity was solidly confirmed by the author in 2004.) With the expansion of composers and good distribution, the somewhat isolated Pennsylvania town of Williamsport had surprisingly strong output, although uneven in quality. The Lincolns added a daughter to the family, Margaret M. Lincoln, born around 1904. The family appeared in Williamsport in the 1910 census with Harry listed as a music composer, and Lottie's younger brother, Leroy Bovec, living in the household.

He did appear to have a fascination with fire, however, as many of his marches seemed oriented towards fires and firefighting, dating back to Midnight Fire Alarm. With Losey as competition, and with the publication of rags by Charles L. Johnson, Charles Cohen and Harry A. Fischler, Lincoln started contributing a small number of syncopations. Even so, piano ragtime in general from Vandersloot was a rarity, in spite of Lincoln's output, which actually exceeded that of E.T. Paull's own compositions. (It should be noted that for some time Fischler was mistakenly considered as yet another pseudonym for Lincoln, but Fischler's identity was solidly confirmed by the author in 2004.) With the expansion of composers and good distribution, the somewhat isolated Pennsylvania town of Williamsport had surprisingly strong output, although uneven in quality. The Lincolns added a daughter to the family, Margaret M. Lincoln, born around 1904. The family appeared in Williamsport in the 1910 census with Harry listed as a music composer, and Lottie's younger brother, Leroy Bovec, living in the household.

He did appear to have a fascination with fire, however, as many of his marches seemed oriented towards fires and firefighting, dating back to Midnight Fire Alarm. With Losey as competition, and with the publication of rags by Charles L. Johnson, Charles Cohen and Harry A. Fischler, Lincoln started contributing a small number of syncopations. Even so, piano ragtime in general from Vandersloot was a rarity, in spite of Lincoln's output, which actually exceeded that of E.T. Paull's own compositions. (It should be noted that for some time Fischler was mistakenly considered as yet another pseudonym for Lincoln, but Fischler's identity was solidly confirmed by the author in 2004.) With the expansion of composers and good distribution, the somewhat isolated Pennsylvania town of Williamsport had surprisingly strong output, although uneven in quality. The Lincolns added a daughter to the family, Margaret M. Lincoln, born around 1904. The family appeared in Williamsport in the 1910 census with Harry listed as a music composer, and Lottie's younger brother, Leroy Bovec, living in the household.

He did appear to have a fascination with fire, however, as many of his marches seemed oriented towards fires and firefighting, dating back to Midnight Fire Alarm. With Losey as competition, and with the publication of rags by Charles L. Johnson, Charles Cohen and Harry A. Fischler, Lincoln started contributing a small number of syncopations. Even so, piano ragtime in general from Vandersloot was a rarity, in spite of Lincoln's output, which actually exceeded that of E.T. Paull's own compositions. (It should be noted that for some time Fischler was mistakenly considered as yet another pseudonym for Lincoln, but Fischler's identity was solidly confirmed by the author in 2004.) With the expansion of composers and good distribution, the somewhat isolated Pennsylvania town of Williamsport had surprisingly strong output, although uneven in quality. The Lincolns added a daughter to the family, Margaret M. Lincoln, born around 1904. The family appeared in Williamsport in the 1910 census with Harry listed as a music composer, and Lottie's younger brother, Leroy Bovec, living in the household.Harry's life did have a little drama and controversy now and then, plus a suggestion of marital infidelity. According to an item in the February 17, 1914 edition of the Williamsport Gazette and Bulletin:

Harry J. Lincoln, who resides at 606 West Edwin Street, and Inez Christian, were arrested last night by the police in a room on East Third Street below Market Square. The arrest was made about 12:30 o'clock. Last night about 11 o'clock Mrs. Lincoln went before Alderman Stead and procured a warrant. The police were given the warrant, located the couple, and breaking down the door found them and took them to headquarters. Both were locked up for the night and will be taken before the alderman this morning for a hearing. Mrs. Lincoln and the Christian girl met at Third and Pine streets Saturday and Mrs. Lincoln pummeled her and tore her hair, telling her what would happen if she did not keep away from her husband.

In spite of this incident and possibly a couple more, Harry and Lottie remained married until his death in 1937.

Another interesting note from that time was his leadership of the Lincoln's Ladies' Band, started in 1915. According to the Williamsport newspaper in early June, "Thousands of people filled the street to get a glimpse of the lady musicians as they headed the Memorial Day parade." The core members of the Lincoln's Ladies' Band included five sisters and two nieces of Jeremiah M. Dockey who initially brought the group together before Lincoln debuted them.

According to the Williamsport newspaper in early June, "Thousands of people filled the street to get a glimpse of the lady musicians as they headed the Memorial Day parade." The core members of the Lincoln's Ladies' Band included five sisters and two nieces of Jeremiah M. Dockey who initially brought the group together before Lincoln debuted them.

According to the Williamsport newspaper in early June, "Thousands of people filled the street to get a glimpse of the lady musicians as they headed the Memorial Day parade." The core members of the Lincoln's Ladies' Band included five sisters and two nieces of Jeremiah M. Dockey who initially brought the group together before Lincoln debuted them.

According to the Williamsport newspaper in early June, "Thousands of people filled the street to get a glimpse of the lady musicians as they headed the Memorial Day parade." The core members of the Lincoln's Ladies' Band included five sisters and two nieces of Jeremiah M. Dockey who initially brought the group together before Lincoln debuted them.During his stint with Vandersloot, and dating back perhaps to 1905, Lincoln had also published some pieces by himself and others under his own monikers, including Harry J. Lincoln Publishing Company and U.S. Music Publishing Company, the latter which would be more frequently used in later years. There is some potential evidence that a local printer, George Furman, the younger brother of Ida Furman-Mulliner who Lincoln had published pieces for, may have been a print jobber or a direct connection to one for Harry's independent publications. In 1918 Harry moved to Philadelphia to re-establish U.S. Music there, but still kept a working relationship with Vandersloot. He is shown there on his draft record in September as a Music Publisher, Composer and Printer. In 1920 he also adds publisher to his census listing in addition to composer and arranger.

In a 1920 directory of Where and How to Sell Manuscripts, Lincoln was represented with the following listing which speaks quite a bit to his personal musical tastes:

HARRY J. LINCOLN MUSIC COMPANY (Formerly United States Music Publishing Company) 2209 Fairmont Avenue, Philadelphia, Penn. Editor, Harry J. Lincoln. Always on the lookout for good semi-high-class songs and good ballads. Original novelty songs can be used at all times. Comic songs are considered, but in order to gain acceptance they must be entirely different from other songs. Can also use good ragtime if not too ragged. Specializes on instrumental music for the band, piano, and orchestra. Reports on manuscripts within two weeks. Buys outright; also on a royalty basis. Return postage should be enclosed with all contributions.

As the advertisement suggests, it appears that starting in 1920, Lincoln wrote tunes for hire from lyricists who sent in their poetry as well, or in some cases arranged existing tunes, using the derived alteration of Harry Jay. In a couple of instances, he contributed lyrics under that name as well. While some of these pieces appeared under the Lincoln imprint, others were published by various jobbers around the east, and many or most of the Harry Jay pieces were copyrighted and published by the lyricist. Composing for hire was not an uncommon practice for many prolific composers or publishers. Many of these tunes were issued as vanity presses, printings of one hundred to one thousand copies, with the client paying for Lincoln's services as composer and arranger taking care of their own distribution, or giving Harry a taste of royalties if he also took care of that aspect of things. The attribution for Lincoln as Harry Jay is made evident in several copyright records of the time in which the pseudonym association is clearly mentioned, and with no evidence to dispute the claim. Perhaps the most telling example of Lincoln's willingness to write for profit was his musical contribution as Harry Jay to the lyrics of We Are the Ladies of the Ku Klux Klan, which might further explain his use of an insulating pseudonym.

others were published by various jobbers around the east, and many or most of the Harry Jay pieces were copyrighted and published by the lyricist. Composing for hire was not an uncommon practice for many prolific composers or publishers. Many of these tunes were issued as vanity presses, printings of one hundred to one thousand copies, with the client paying for Lincoln's services as composer and arranger taking care of their own distribution, or giving Harry a taste of royalties if he also took care of that aspect of things. The attribution for Lincoln as Harry Jay is made evident in several copyright records of the time in which the pseudonym association is clearly mentioned, and with no evidence to dispute the claim. Perhaps the most telling example of Lincoln's willingness to write for profit was his musical contribution as Harry Jay to the lyrics of We Are the Ladies of the Ku Klux Klan, which might further explain his use of an insulating pseudonym.

others were published by various jobbers around the east, and many or most of the Harry Jay pieces were copyrighted and published by the lyricist. Composing for hire was not an uncommon practice for many prolific composers or publishers. Many of these tunes were issued as vanity presses, printings of one hundred to one thousand copies, with the client paying for Lincoln's services as composer and arranger taking care of their own distribution, or giving Harry a taste of royalties if he also took care of that aspect of things. The attribution for Lincoln as Harry Jay is made evident in several copyright records of the time in which the pseudonym association is clearly mentioned, and with no evidence to dispute the claim. Perhaps the most telling example of Lincoln's willingness to write for profit was his musical contribution as Harry Jay to the lyrics of We Are the Ladies of the Ku Klux Klan, which might further explain his use of an insulating pseudonym.

others were published by various jobbers around the east, and many or most of the Harry Jay pieces were copyrighted and published by the lyricist. Composing for hire was not an uncommon practice for many prolific composers or publishers. Many of these tunes were issued as vanity presses, printings of one hundred to one thousand copies, with the client paying for Lincoln's services as composer and arranger taking care of their own distribution, or giving Harry a taste of royalties if he also took care of that aspect of things. The attribution for Lincoln as Harry Jay is made evident in several copyright records of the time in which the pseudonym association is clearly mentioned, and with no evidence to dispute the claim. Perhaps the most telling example of Lincoln's willingness to write for profit was his musical contribution as Harry Jay to the lyrics of We Are the Ladies of the Ku Klux Klan, which might further explain his use of an insulating pseudonym.During the next few years Harry contributed a great number of pieces to piano roll manufacturers, Wurlitzer being the primary outlet. Many of them did not appear in print, also a common practice related to both piano rolls and phonograph records. Harry also worked at acquiring a number of other publishing companies to add to the U.S. Music collection, including the Vandersloot catalog in 1929. Frederick Vandersloot died in 1931 and the firm then ceased to exist except under Lincoln's Philadelphia imprint.

The only viable work that Lincoln had from the Vandersloot catalog in the early 1930s was the ubiquitous Repasz Band, as most of the marches and waltzes were now musical dinosaurs in the jazz age. After the copyright renewal in 1929, Harry composed Repasz on Parade, and boldly included the following information in the header:

This march was written as a companion piece to the famous 'Repasz Band March,' which is one of the best known and most popular marches now on the market. The fundamental idea in writing this march came to the composer after thousands of letters had been received from time to time asking that the composer of that great march write a companion piece to it, and as the name Chas. C. Sweeley, which appeared on Repasz Band March as its composer was merely the pen name of Harry J. Lincoln, who wrote hundres of big selling things, it was therefore, up to Mr. Lincoln to write this great companion number. The author has attempted to make Repasz on Parade equally as catchy and pleasing as the Repasz Band March and trusts his efforts in this march may meet with the same general support accorded his other march compositions.

The jury remains out to this day on the legitimacy of this claim.

Lincoln did write a couple of novelty works in the late 1920s, including Hickory Nuts Rag and Kick Off, but could not keep up with the true novelty composers of the era. In 1926 he had released the book How to Write and Publish Music containing a lifetime of his experience in both fields. In 1931 he released an expanded and revised edition largely intended for the self-starter during the uncertain time of the Great Depression. A supplement includes a list of "music publishers and dealers, band and orchestra leaders, music jobbers, phonographic recording companies, 25 cent store headquarters, [and] radio stations." Yet little is contained in the book about Lincoln himself.

In 1931 he released an expanded and revised edition largely intended for the self-starter during the uncertain time of the Great Depression. A supplement includes a list of "music publishers and dealers, band and orchestra leaders, music jobbers, phonographic recording companies, 25 cent store headquarters, [and] radio stations." Yet little is contained in the book about Lincoln himself.

In 1931 he released an expanded and revised edition largely intended for the self-starter during the uncertain time of the Great Depression. A supplement includes a list of "music publishers and dealers, band and orchestra leaders, music jobbers, phonographic recording companies, 25 cent store headquarters, [and] radio stations." Yet little is contained in the book about Lincoln himself.

In 1931 he released an expanded and revised edition largely intended for the self-starter during the uncertain time of the Great Depression. A supplement includes a list of "music publishers and dealers, band and orchestra leaders, music jobbers, phonographic recording companies, 25 cent store headquarters, [and] radio stations." Yet little is contained in the book about Lincoln himself.As of the 1930 census, Harry and Lottie were residing near downtown Philadelphia, and Harry listed himself with no career at that time, unusual considering his continuing musical activity. Their daughter, Margaret, was living with them at that time, and the census also lists an adopted son, Harry J. Lincoln Jr., who had been born in January 1929. One of Lincoln's descendants suggests that it may have been Margaret's child out of wedlock, adopted to save face, but this has not been confirmed. Lincoln evidently had a role as an engraver with the Otto Zimmerman & Son Company in Cincinnati, Ohio, during the 1930s, which was mentioned in an article about a year after his passing. This was also the company that released his how-to book. Harry J. Lincoln died in Philadelphia just after his 59th birthday, having not left behind any concise record of his output and having not formally settled selected disputes over authorship.

As a person, Lincoln was rather unassuming and seemingly businesslike, warranting little attention outside the Repasz Band controversy and the incident with Miss Christian, and only scant mentions in the Williamsport newspaper through the years. The consummate small-town corporate musician, a day at the office for him was just as likely approving plates for printing or negotiating terms with another composer or artist as it was to write another march or tweak an arrangement of a song. Vandersloot's national success publishing from a simple Pennsylvania town can attributed largely to Lincoln's management and output. While he wrote very little ragtime, and only average quality music for the most part, he is still a substantial part of the overall output of instrumentals of the ragtime era. We will likely never know all of the pseudonyms or other composer's names he wrote under or for (or even masqueraded as or borrowed from). But what we do have represents some of the easier to play and interpret pieces of the era, and a representative piece of rural Pennsylvania for certain.

Thanks to some assistance from the Lycoming Historical Society for information on the region. Also to Cheryl Licary for some verification and the addition of a few pieces, in addition to pushing an investigation into the existence of Carl Loveland. Charles Sweeley, son of the composer, contributed valuable information concerning his family's stance on Repasz Band. Chris Buckingham, a descendant of Lincoln, contributed information that led to the discovery of the Harry Jay listings.