Harry Von Tilzer (Aaron Gumbinsky) (July 8, 1872 to January 10, 1946) | |

Compositions Compositions | |

|

1892

I Love You Both1895

My Sweet T'ing1897

De Swellest Ladies' Coon in Dis Yer TownI've Scratched You Off Ma' List [1] The Dear Good Mr. Best: March Song [1] I'se Got Another Nigger on Ma Staff [1] 1898

My Pretty PollyRastus Thompson's Rag-Time Cake Walk When You Do De Rag-Time Dance When You Do De Rag-Time Dance (Song) My Old New Hampshire Home [1] I'll Be a Sister to You [1] Just Come Up and Take Your Presents Back [1] I Wonder If She's Waiting [1] Jack and the Beanstalk or Stories that My Mother Told Me [1] My Home of Long Ago [w/Maurice Shapiro] 1899

I Guess That Will Be About AllThe Rag Time Dance I Wouldn't Leave My Home if I Were You Mammy's Kinky-Headed Coon Where The Sweet Magnolias Bloom The Coldest Coon In Town [1] I've Lost Ma Baby [1] My Black Bess [1] I Wonder If She's Waiting [1] I'd Leave Ma Happy Home for You [2] I've Just Received A Telegram From Baby [2] 1900

I've Got a Gal For Ev'ry Day in the WeekOh! Oh! Miss Phoebe [1] The Sun Will Shine Again [1] 'Rauss Mit Ihm [2] A Bird In A Gilded Cage [3] When Wealth and Poverty Meet [3] The Spider and the Fly [3] I Ain't A-Goin to Weep No More [4] Susie [4] When Harvest Days are Over, Jessie Dear [w/Howard Graham] Marching to the Music of the Band [w/Richard Goodall] Excelsior: A Sublime Sacred Song [w/Leontine Stanfield] My Jersey Lily [w/Arthur Trevelyan] 1901

W'hoa Bill: A Country CharacteristicDown Where The Cotton Blossoms Grow [1] Can You Blame Me For Lovin' That Man? [1] Whoa Bill (Song) [4] My Whip-Poor-Will [4] My Lady Hottentot [5] Are You a Buffalo? [6] 1902

Razzle Dazzle: Characteristic Cake WalkChocolate Drops: A Darktown Improbability Melinda's Ragtime Ball On a Sunday Afternoon [1] Jennie [1] Somebody's Waiting for Me [1] I'll Be There, Mary Dear [1] When Kate and I Were Coming Thro' the Rye [1] My Bamboo Queen [1] The Train Rolled On [1] Oh, the Girls, the Lovely Girls [1] Arabella [1] I Just Can't Help From Lovin' That Man [1,7] Come and Meet Me Sadie [1] Won't You Roll Dem Eyes [1] The Mansion of Aching Hearts [3] The Banquet in Misery Hall [3] Jennie Lee [3] In the Eternal City [3] The Chink of the Miser's Gold [3] Little Maizy Jones [4] My Twilight Queen [4] When the Troupe Comes Back to Town [4] Since Imogene Went to Cooking School [4] Lazy Little Mazie Jones [4] When I Hear the Music in the Park [6] Down Where the Wurzburger Flows [7] In the Sweet Bye and Bye [7] You Couldn't Hardly Notice It at All [7] My Midnight Rose [7] It Must Have Been Svengali in Disguise [7] Watching and Waiting for You, Love [7] Beautiful Fairy Tales [7] My Sunrise Sue [7] I Want to Be a Actor Lady [7] Pardon Me, My Dear Alphonse, After You, My Dear Gaston [7] Meet Me When the Sun Goes Down [7] The Song the Soldiers Sang [7] My Firefly [8] Down on the Farm [8] I'm Getting Awful Lazy [8] My Cocoanut Queen [8] 1903

Keep Off the Grass: Barn DanceWhen My Johnnie Boy Goes Marching By [1] Under the Anheuser Bush [1] My Little Coney Isle [1] Good Bye Eliza Jane [1] My Dixie Lou [1] Whose Little Dear Little Girlie is Oo! [1] Trixie [1] Isn't it Lovely to Be on the Stage [1] The Girl You Left Behind [1] Down Where the Swanee River Flows [1] Oh! Jenny Johnson [1] When the Leaves Begin to Fall [1] What a Beautiful World This Would Be [1,8] Ephasafa Dill [1,9] Down at the Old Bull and Bush [1] [w/Russell Hunting & Percy Krone] Mammy's Little Alabama Love [3] You'll Have to Read the Answer in the Stars [7] I Wouldn't, Would You? [w/Jacob Ralph Abarbanell] Wouldn't it Make You Hungry? [w/Frank Abbott] The Fisher Maiden: Musical [3] Oh Marjory * Laughing Song * I'm In Love with the Beautiful Bugs I'm a Fisher Maiden Let the Band Play a Pleasing Tune * On a Beautiful Distant Island We're Secret Society Members He Dangled Me on His Knee Maydee * Under the Mulberry Tree A Daughter of the Moon Am I The Highly Important Fly * Roses for the Girl I Love Down on the South Sea Isle * A Sail on the Tail of a Whale * When You Go to London Town, Gay Paree or Dixieland Coo-ee Coo-ee Beneath the Palms of Paradise I'll Dream of You if You'll Dream of Me 1904

Cornfield Capers: A Hayseed MarchMy Kickapoo: Indian Characteristic My Pretty Little Kickapoo [1] All Aboard for Dreamland [1] Ebenezer Brown [1] Hannah Won't You Open the Door? [1] The Palace of Silver and Gold [1] You Can't Loose Me Lulu [1] Come On Boys, Let's Follow the Band [1] The Man with the Dough [1] Down Where the Sweet Potatoes Grow [1] Have You Seen Maggie Riley [1] She's a Yankee Doodle Girl [1] Louisa Schmidt [1] Go On and Coax Me [1] When the Frost is On the Pumpkin [1] Abraham [1] Alexander, Don't You Love Your Baby No More? [1] I'll Be Missing All Your Kissing Bye and Bye [10,11] Down at the Baby Store [12] Sweet Dora Dell [12] Underneath a Chestnut Tree [w/Will Gumm] The Jolly Baron (Miller's Daughter): Musical (* from The Fisher Maiden) I'm the Miller's Daughter [10,11] Mum's the Word [10,11] Kalamazoo is No Place for You [10,11] (On A Holiday) In Vacation Time [10,11] The Magic Man [3] 1905

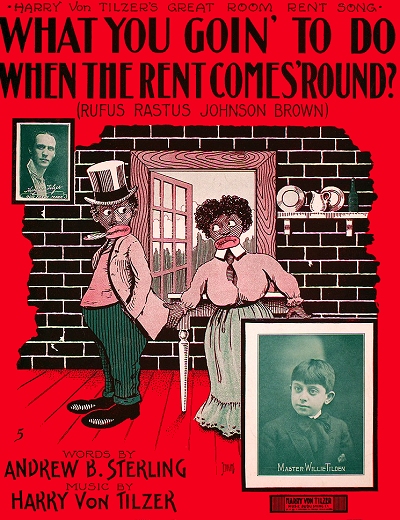

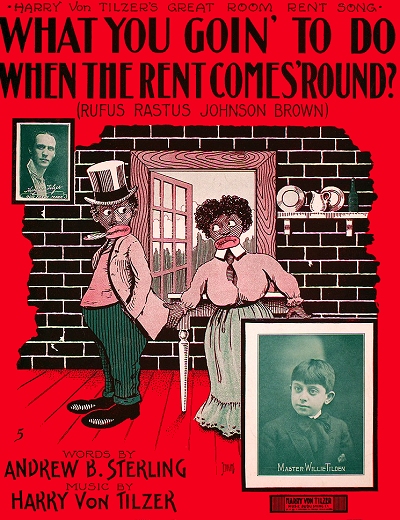

I'm the Only Star That Twinkles onBroadway [1] Wait 'Till the Sun Shines, Nellie [1] What You Goin' to Do When the Rent Comes 'Round? (Rufus Rastus Johnson Brown) [1] On the Banks of the Rhine With a Stein [1] In a Hammock Built for Two [1] On the Strict Q.T. [1] Mamie McIntyre [1] Where the Morning Glories Twine Around the Door [1] Just Across the Bridge of Gold [1] Making Eyes [1] Marching Home with Rosie [1] And the Great Big World Went 'Round and 'Round [1] Riding on Top of the Car [7] [w/Fred W. Leigh] With You in a Bungaloo [w/Fred Wayne] Heigh Ho: Musical [10] 1906

When the Flowers Bloom in Spring-Time,Molly Dear [1] Look Who's Here! Ship Ahoy [1] Home Sweet Home Sounds Good To Me [1] Would You Leave Your Happy Home For Me? [1] I Never Saw Such Jealousy in All My Life [1] Oh! Mister Brown [1] The Good Old Songs of the Blue and Gray [1] Moving Day [1] Are You Coming Out To-Night Mary Ann? [1] In a Chimney Corner (On a Winter's Night) [1] Ida-Ho [1] Abraham Jefferson Washington Lee (You Ain't Goin' To Pick No Fuss Out Of Me) [1] The Songs of the Rag Time Boy [1] The Beautiful Land of Love [3] 1907

Mariutch Down at Coney Isle [1]Darling Sue [1] Top o' the Mornin' [1] Take Me Back to New York Town [1] Take Me Back to Melbourne Town [1] Top O' the Mornin' "Bridget McCue" [1] Bye Bye Dearie [1] Oh, Oh, Miss Lucy Ella [1] I'd Like to Be Your Affinity [1] Sacramento [1] Lu-Lu and Her La-La-La [3] When Miss Patricia Salome Did Her Funny Little Oo-La-Pa-Lome [7] Hello! Mister Stein [7] I Got to See de Minstrel Show [7] When I Was in the Chorus of the Gaiety [32,33] 1908

Just to While the Hours Away [1]Sometime [7] Ain't You Coming Out Tonight? [1] Mary Ann O'Houlihan [7] Pass it Along to Father [7] I Remember You [7] Don't Take Me Home [7] I Want to Go Along with You [7] In a Garden of y'Eden for Two [7] Just One Sweet Girl [13] He Went a-Hunting [13] Schooners That Pass in the Night [13] When Highland Mary Did the Highland Fling [13] Summertime [13] 1909

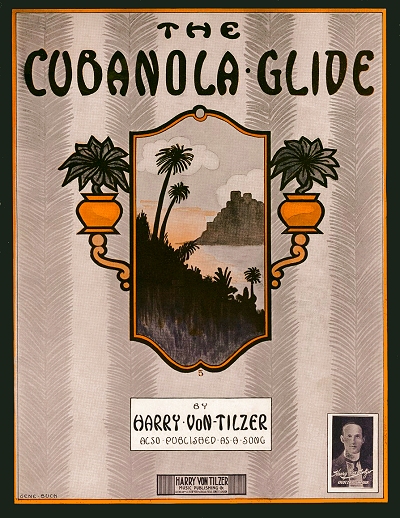

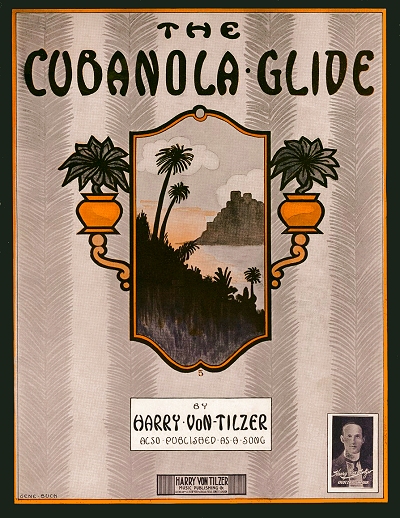

The Cubanola Glide (Instrumental)Harry Von Tilzer's Society Barn Dance My Wife Ain't Coming Back [1] The Cubanola Glide (Song) [7] Waltzing [7] Keep Your Foot on the Soft Pedal [14] I Love I Love I Love My Wife (But Oh! You Kid!) [w/Jimmy Lucas] The Beautiful Sea [32,33] Take Me Up to the Roller Rink [w/George Armstrong] The Kissing Girl: Musical [7] Love is Like a Rose Come, Little Girl and Dance With Me My Sweet One Major General Pumpernickel Good Old German Beer! Soldier Boy When You Kiss the One You Love A Hair Of The Dog That Bit You Swinging on the Old Grape Vine The Little Band of Gold On the B, On the Bou, On the Boulevard The Laughing Song The Things I Am Going to Do Love's Golden Dream 1910

I Love It (Instrumental)All Aboard for Blanket Bay [1] The Good Old Days Gone By [1] I'm an Honorary Member of the Patsy Club [1] Funny Face: A New Pet Name [1] And I Thought He Was a Business Man [1] Gallagher Says You Can't Keep the Irish Down [1] Under the Yum Yum Tree [1] Bright Lights Gay, or, the New Mown Hay [1] Help, Help, Help, I'm Falling in Love [7] Give My Regards to Mabel [7] Ring-a-Ding-Dong [w/Edward Clark] That's Genuine First Class Yiddisha Love [10] He's Awfully Fond of My Husband [10] I Will Be Your Chantecler [10] When Mariola do the Cubanola [14] I Don't Believe You [14] Tell It To Sweeny [14] Hip, Hip, Hypnotize Me [14] Hurrah for the Summertime [15] That Lazy Drag [15] The Mad Madrid [16] That Yodeling Rag [16] The Hindoo [16] I Love It [34] I'll Lend You Everything I've Got Except My Wife [w/Jean C. Havez] Steve [w/William F. Kirk] 1911

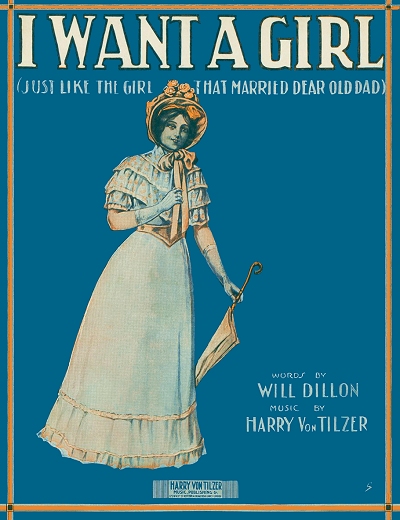

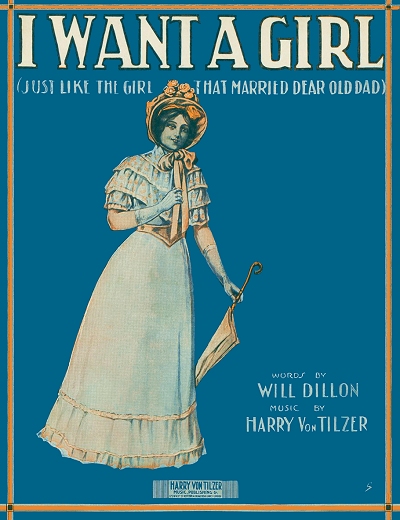

At the Folies Bergere [1]I Don't Want Any Other Sweetheart if I Can't Have You [1] Just a Little Love [1] The Ragtime Goblin Man (Song) [1] Hot Stuff [1] Does Anybody Want to Take Charlie's Place? [1] My Counterfeit Bill [1] Knock Wood [1] Take a Look at Me Now (Remember When I First Came to Town) [1] My Carolina Cutey [1] The Base Ball Glide [1] With His Little Cane and Satchel in His Hand [5] Way Down in Mexico [5] Missouri Joe [7,34] Come Back to Aaron [10] I Love It [14] You Don't Love Me Half as Much as I Love You [14] April Fool [14] Shut Your Eyes and Make Believe [14] Don't Leave Me Now [14] I Want a Girl (Just Like the Girl that Married Dear Old Dad) [14] Shut Your Eyes and Make Believe [14] They Always Pick on Me [17] Knock a Little Louder, Ephraham [17] 1912

The Ragtime Goblin Man (Instrumental)The Ghost of the Goblin Man [1] Just a Little Lovin' for Baby Please [1] Somebody Else is Gettin' It [1] Last Night Was the End of the World [1] Let's See, Um, Um, That's Right [1,15] Snap Your Fingers, and Away You Go [5] Waiting for Me [5] When Dear Old Santa Claus Comes to Town [5] Put On Your Old High Hat [5] The Villain Still Pursued Her (Dance With Me) [5] The Green Grass Grew All Around [5] The Ragtime Wagon of Love [5] Who Puts Me In My Little Bed (My Mamma Dear) [5] The Bunny Hug [5] I'd Do As Much For You (Hmm--We're Having Lovely Weather) [5] Gliding Through the Old Stage Door [5] I Left My Old Kentucky Home for You [5] The Girl I Left Before I Left the Girl I Left Behind [13] It's the Girl Behind the Man [17] 1913

Candy Kisses: Turkey TrotCedro! My Italian Romeo [1] The Gum Shoe Man [1] Don't Stop [1] Where Is She Now? [1] Lucky Boy [1] |

1913 (Cont)

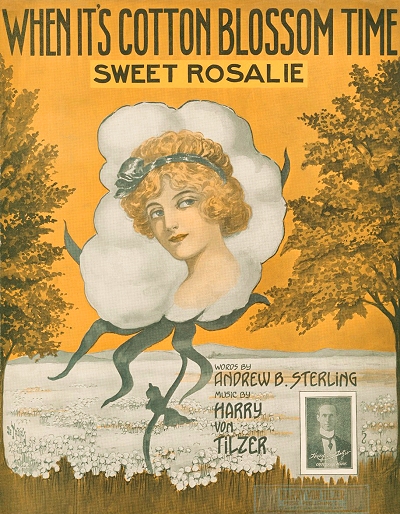

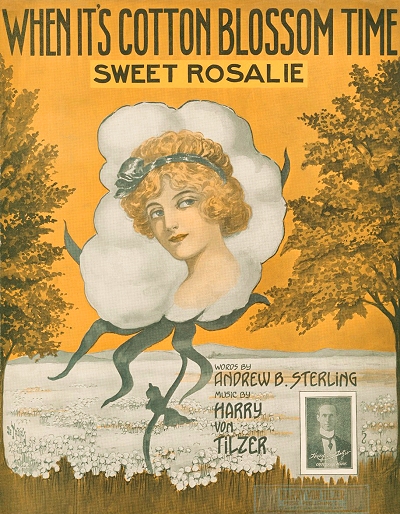

As Long as the World Goes Round (I WillLove You) [1] Won't You Please, Have a Heart? [1] Since Mrs. McNott Learned to Do the Turkey Trot [1] The Song That Stole My Heart [1] Love When You Speak of Love (That's My Name) [1] I Never Heard of Anybody Dying From a Kiss (Did You?) [1] When You Said Good Bye [1] Do You Take This Woman For Your Lawful Wife (I Do, I Do) [1] When It's Cotton Blossom Time (Sweet Rosalie) [1] On the Old Fall River Line [1,5] What a Fool I'd Be [1,5] Good Bye Boys [1,5] A Little Bunch of Shamrocks [1,5] I Had a Devil of a Time [5] Gee, I Wish I Was Big [15] Love Me While the Loving is Good [17] What's the Good of Being Good When No One's Good to Me [17] Oh, Play That Umpah, Umpah, Umpah, on Our Umpah Honeymoon [18] On My Chicken Farm [18] Swing, Swing, Swing (He'd Roll His Hammock Up and Say "Good-Night") [18] When Michael Dooley Heard the Booley Booley [18] Come and Kiss Your Little Baby [19] 1914

Love's Memories: WaltzesPoppy: Tango San Francisco Tingle Tangle: Fox Trot We'll Paddle Our Own Canoe [1] A Real Moving Picture From Life [1] I Wonder Who Wished Her on Me [1] Hands Off [1] You Can Tango, You Can Trot, Dear, But Be Sure and Hesitate [1] In Our Own Little Heaven Down Below [1] Honey You Certainly Know How to Love [1] Twenty Five Minutes Away [7] They All Had a Finger in the Pie [7] Johnny on the Spot [7] The Dove of Peace [7] I Knew Him When He Was All Right [7] Why Do Your Kisses Taste So Sweet? [15] If It Wasn't for You [15,20] Baby Love [15,20] Leave Me Alone [15,20] 1915

Somebody KnowsUnder the American Flag [1] Those Musical Eyes [1] Tell Me Some More (I Just Came Home Myself) [1] You'll Always Be The Same Sweet Girl [1] I'm Homesick [1] I'm Proud to Be the Mother of a Boy Like You [1] Love Me Nice [1] You Can't Get Arrested for Thinking [1] Alagazam, to the Music of the Band [1] Out Side of That Why, He's All Right [1] Close to My Heart [1] After Tonight, Good-Bye (Just for Tonight) [1] Springtime Wagon of Love [5] Hello, Boys, I'm Back Again [7] Cows May Come and Cows May Go, But the Bull Will Go On Forever [7] When Sunday Comes to Town [7] Roaming Around [7] When My Ship Comes In [7] Dear Old-Fashioned Irish Songs My Mother Sang to Me [7] Go and Get the Habit [7] Abie and Me and the Baby [19] Cheer Up, The Worst is Yet to Come [21] Sleepy Moon [22] General Hooligan [w/Ray Sherwood] 1916

Since Mary Ann McCue Came Back fromHonolu On the South Sea Isle Sometimes You Get a Good One and Sometimes You Don't [1] In the Evening By the Moonlight, Dear Louise [1] (Sweet Babette) She Always Did The Minuet [1] I Sent My Wife To The Thousand Isles [1,6] Honest Injun [1,6] This Great Big World Owes Me a Loving [1,6] Pretty Please [13] Brutus, Caesar, Anthony Lee [13] The Ghost of the Terrible Blues [13] That's the Meaning of Ireland [13] I Might Be Coaxed Dear, But Not By You [13] Through These Wonderful Glasses of Mine [13] When Priscilla Tries to Reach High C [13] You Were Just Made to Order for Me [13] When Uncle Sammy Leads the Band [21] On the Hoko Moko Isle [21] It's a Hundred to One You're in Love [21] There's Someone More Lonesome Than You [21] Tho' I Had a Bit O' the Divil in Me She Had the Ways of an Angel, Had She [22] There's a Little Bit of Scotch in Mary [23] Marry a Girl from the Ten Cent Store [23] [w/Eddie Doerr] With His Hands in His Pockets and His Pockets in His Pants [w/Jeff Morgan] Don't Slam the Door [w/Billy Lynott] 1917

The Man Behind the Hammer and the PlowAt the Old Town Pump Stolen Sweets: Waltzes There's A Million Reasons Why I Shouldn't Kiss You (But I Can't Think Of One) [1] Just Help Yourself [1] Just As Your Mother Was [1,23] Says I to Myself, Says I [6] Some Little Squirrel is Going to Get Some Little Nut [6] Buy a Liberty Bond for the Baby [6] If Sammy Simpson Shot the Chutes Why Shouldn't He Shoot the Shots [6] In the Days of Auld Lang Syne [6] Bring Back, Bring Back, Bring Back the Kaiser to Me [6] [w/Adele Rowland] And Then She'd Knit, Knit, Knit (Another Row, Row, Row) [6] Down Where the Sweet Potatoes Grow [6] I'll Be the Words And You'll Be the Music [13] I'm a 12 O'clock Feller in a 9 O'Clock Town [15] [w/Bert Kalmar] Just the Kind of a Girl You'd Love to Make Your Wife [21] Love Will Find the Way [22] Yukaloo (Pretty South Sea Island Lady) [22] Isn't She the Busy Little Bee [23] Somewhere in Dixie [23] When You Waltz With the Girl You Love [23] Help! Help! Help! I'm Sinking in a Beautiful Ocean of Love [23] Wonderful Girl (Good Night!) [23] Listen to the Knocking at the Knitting Club [24] Constantinople (Con-stan-ti-no-ple) [24] He's Doing His Bit for the Girls [24] Cross My Heart and Hope to Die [24] Every Day is Sunday for Billy [24] It's a Long Long Way to the U.S.A. (And The Girl I Left Behind) [w/Val Trainor] 1918

Can You Tame Wild Wimmen? [1]You'll Have to Put Him to Sleep With the Marseillaise (And Wake Him Up with a Oo-La-La) [1] Keep the Trench Fires Going (For the Boys Out There) [6] Waiting For the Tide to Turn [6] Mama's Captain Curly Head [6] In the Good Old Irish Way [6] I Want a Doll [6,7] Bye and Bye You'll See The Sun a-Shining [6,7] I'm Just an Old Jay From the U.S.A. [6,7] Taffy [7] The Makin's of the U.S.A. [7] You Don't Know What You're Missing if You Never Had a Kiss [7] Pa, Ma, and a Pretty Little Miss [7] The Little Good For Nothings (Good For Something After All) [21] I Couldn't Go to Ireland so Ireland Came to Me [21] He's Well Worth Waiting For [23] On the Sandwich Isles [23] It Gets A Little Shorter Every Day [23,26] Jim, Jim, Don't Come Back 'till You Win [24,25] Jim, Jim, I Always Knew You'd Win [24,25] Batter Up (Uncle Sam is At the Plate) [w/Harry Tighe] 1919

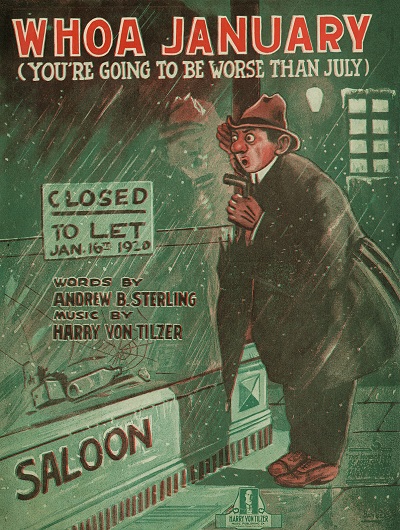

Why Do They Play Here Comes the BrideWhen They Ought to Play There Goes The Groom? [1] They're All Sweeties [1] Whoa January (You're Going to be Worse Than July) [1] It's a Small World After All [1] When Mariutch Shake a da Shimmie Sha Wob [1] Just Another Poor Man Gone Wrong [1] Dreams [1] He Used to be a Farmer But He's a Big Town Slicker Now [1] Somebody's Waiting for Someone [1] I Ain't'en Got'en No Time to Have The Blues [1] He Went In Like a Lion and Came Out Like a Lamb [1] What Could be Sweeter? [1,27] Sure, an' it's Me that Knows a [7] Does Anybody Want My Fido? [23] Steven Got Even [24,25] Mad Love: Musical [35] Alone in the Dark 1920

Just As We Used to BeWhen The Harvest Moon Is Shining [1] Why Did You Do It to Me, Babe? [1] Tra La La La La [1] Clysmic Water: Daughter of White Rock [5] That Old Irish Mother of Mine [5] If I Meet the Guy Who Made This Country Dry [5] Weegee Weegee (Ouija Ouija) Tell Me Do [5] Mammy's Good Night Lullaby [5] My Lady Hottentot [5] You May Be the World to Your Mother (But You're Only An Oil Can To Me) [5] Oh Dear, Oh Dear [6] I Want to Go to The Land Where the Sweet Daddies Grow [6] If I Wait 'till the End of the World [26] I've Got the A B C D Blues [26] Silver Water [26] 1921

Jack, How I Envy YouSomebody's Mother [1] She Walks in Her Husband's Sleep [1] You're a Good Old Car (But You Can't Climb Hills) [1,6] I Love That [1,6] Down in Midnight Town [1,6] Humpty Dumpty [1,6] In That Little Irish Home Sweet Home [5] If They Ever Take the Sun Out of Sunday [5] Save the Daylight for Somebody Else But Save the Moonlight for Me [13] The Scandal of Little Lizzie Ford [27] On King Solomon's Farm [27] 1922

A Picture Without a Frame [1]You'll Get All That's Coming to You [1] Behind the Clouds There's Always Sunshine [1] It's Raining [1] Meet the Wife [1] On the Umpah Isle [1] The Rosary You Gave to Me [1,6] Those Days are Over [1,6] Ain't You Coming Out Malinda? [1,6] Mammy Lou [1,6] Harry Von Tilzer's Old-Time Favorite Hits 1923

Old King Tut (In Old King Tutenkhamen'sDay) [5] In the Land Where the Green Shamrock Grows [5] Spoony Bill [13] Dear Old Lady [26] Chief Hokum [26] When Your Bluebird Flies Away [26] I'll Be With You When the Roses Bloom in the Spring [26] My Boy Friend [26] The Little Wooden Whistle Wouldn't Whistle [27] School Time [27] Chase Me Charlie [w/Gordon McConnell & Eddie Gorman] 1924

Little Moth, Keep Away from the Flame [9]She Fell Down on Her Cadenza [27] I'll Make the Pies Like Mother (if You'll Make the Dough Like Dad) [27] I Just Can't Make My Heart Behave [28,29] Oh You Can't Fool an Old Hoss Fly [28,29] Sister Hasn't Got a Chance Since Mother Bobbed Her Hair [28,29] Wandering One [w/Harry Mayo] 1925

When the Golden Rod is Waving, Annie DearJust Around the Corner (May be Sunshine for You) [30] I Want My Rib [30] Gee! But It's Sweet to Cheat Just a Little [30] What Does Little Sweetie Want? [w/Joe Manuel] 1926

All the Boys Keep Looking DownUnder a Wurzburger Tree Sweet Stuff [30] What's Good Enough for Washington is Good Enough for Me [30] That's Where I Meet My Girl [30,31] Keep a Little Sunshine in Your Heart [w/Ted Lewis] 1927

All I Want is Just Your Love [26]You Can't Eat Peas With a Knife [27] Whether It Rains, Whether It Shines [30] When It's Necking Time in Great Neck [30] 1928

Out of a Clear Blue Sky [30]If Mother Could Only See Me Now [30] I'm Happy, Now That You're Gone [w/Vic Meyers] 1929

Heigh Ho: Musical Revival [30]Breathin' Heavy You're My Little Theme Song In You All My Dreams Come True The Nonchalant: Dance Lookin' Hot and Keepin' Cool 1934

Just Across the River on the Hill1935

I Ain't Gonna Love No More [6]Why did Bluebeard's Beard Turn Blue? [6] What's Gonna Be the Outcome if the Income Don't Come In? [6] Down at the Old Minstrel Show [6] [w/Nick Kenny] 1936

In Our Cocktail of Love [31]1941

The Swing-Time Boogie-Boo Man [1]1943

Sierra Moonlight [w/Albert Von Tilzer]

1. w/Andrew B. Sterling

2. w/Will Heelan 3. w/Arthur J. Lamb 4. w/George Totten Smith 5. w/William Jerome 6. w/Edward (Eddie) P. Moran 7. w/Vincent P. Bryan 8. w/Raymond A. Browne 9. w/Bartley Costello 10. w/Addison Burkhardt 11. w/Aaron S. Hoffman 12. w/Alfred Bryan 13. w/Jack Mahoney 14. w/Will Dillon 15. w/George Whiting 16. w/Edward Madden 17. w/Stanley Murphy 18. w/Everett J. Evans 19. w/Lew Brown 20. w/Paul Cunningham 21. w/Lou Klein 22. w/Walter Van Brunt 23. w/Garfield Kilgour 24. w/Bert Hanlon 25. w/Ben Ryan 26. w/George A Kershaw 27. w/Billy Curtis 28. w/Blanche Franklyn 29. w/Nat Vincent 30. w/Dolph Singer 31. w/J. Vincent Healey 32. w/Arthur Wimperis 33. w/Walter Davidson 34. w/E. Ray Goetz 35. w/Frances Nordstrom |

Famous as both a publisher and a songwriter, Harry Von Tilzer and his brothers Albert Von Tilzer and Will Von Tilzer represent another great success story of the ragtime era, even though they more or less wrote about and promoted ragtime, never writing any actual rags. They also prove to be a bit frustrating in terms of research, since much of the information on their early lives was relayed by the brothers themselves, and matching facts before 1900 are hard to corroborate. But a find has been made here that adds some interest to the Von Tilzer story.

Early Years

Given their birth dates and locations, and matching the demographics of their parents, it appears that the brothers were born to Jacob Gumbinsky (or Gummbinsky) and Sarah Tilzer, Polish immigrants who may have actually lived in Germany before coming to the United States. In later years, Albert often put Indiana as their place of birth, and Harry and Jacob switched between Germany and Poland, which was a little more helpful. Older brother Jules lists Russia, which is even more consistent with Poland. Given that all other factors match, it is likely that Harry was born as Aaron Gumbinsky in Detroit, Michigan, as were his older brothers Louis (9/22/1870 - later Jacob or Jack) and Julius (11/1868 - later Jules). There were also two other siblings, one boy and one girl, but they died in infancy in 1873 and 1874.

Between 1874 and 1877 the family moved from Detroit to Indianapolis, Indiana, where Albert was born as Elias Gumbinsky (3/29/1878), Albert possibly being a middle name. In the 1880 census, their father Jacob is listed as a hair dresser, but later owned a shoe store, then expanded that into a general store. Sarah worked as a milliner in the store as well. He is listed in the Indianapolis directories of the 1880s as selling "furniture, stoves and tinware" at 434 S. Illinois Street. Harry's memories recall a shoe store, and this would be somewhat consistent, as shoes might be found in such a location. Younger brother Harris Harold, the eventual lawyer for the Von Tilzer brothers, was born in September 1880, followed by Wilbur (Will) in November 1882. This find means that there was a big change in their names (except H. Harold who retained Gumm) and lives following Harry's lead. It has also been said that the family changed their name to Gumm at some point, although this is more likely Harry and Albert since their father was still using Gumbinsky in the 1890s.

He is listed in the Indianapolis directories of the 1880s as selling "furniture, stoves and tinware" at 434 S. Illinois Street. Harry's memories recall a shoe store, and this would be somewhat consistent, as shoes might be found in such a location. Younger brother Harris Harold, the eventual lawyer for the Von Tilzer brothers, was born in September 1880, followed by Wilbur (Will) in November 1882. This find means that there was a big change in their names (except H. Harold who retained Gumm) and lives following Harry's lead. It has also been said that the family changed their name to Gumm at some point, although this is more likely Harry and Albert since their father was still using Gumbinsky in the 1890s.

He is listed in the Indianapolis directories of the 1880s as selling "furniture, stoves and tinware" at 434 S. Illinois Street. Harry's memories recall a shoe store, and this would be somewhat consistent, as shoes might be found in such a location. Younger brother Harris Harold, the eventual lawyer for the Von Tilzer brothers, was born in September 1880, followed by Wilbur (Will) in November 1882. This find means that there was a big change in their names (except H. Harold who retained Gumm) and lives following Harry's lead. It has also been said that the family changed their name to Gumm at some point, although this is more likely Harry and Albert since their father was still using Gumbinsky in the 1890s.

He is listed in the Indianapolis directories of the 1880s as selling "furniture, stoves and tinware" at 434 S. Illinois Street. Harry's memories recall a shoe store, and this would be somewhat consistent, as shoes might be found in such a location. Younger brother Harris Harold, the eventual lawyer for the Von Tilzer brothers, was born in September 1880, followed by Wilbur (Will) in November 1882. This find means that there was a big change in their names (except H. Harold who retained Gumm) and lives following Harry's lead. It has also been said that the family changed their name to Gumm at some point, although this is more likely Harry and Albert since their father was still using Gumbinsky in the 1890s.While living in Indianapolis, Harry, Julius and Albert were exposed to the joys of stage entertainment as a local theatrical company gave performances in the loft above their father's store. Harry had also been playing piano at an early age, largely, as he recalled, with encouragement from his mother. Albert also followed in Harry's footsteps with similar musical talent. Harry was so enraptured with the lure of performance that he lived out the fantasy of many young boys and left home to join the Cole Brothers Circus in 1886 at age 14. With them he worked as a tumbler and singer, playing the calliope and piano as well.

He left the circus before he was 16 to perform with traveling Burlesque and Vaudeville shows playing piano and writing tunes and incidental music for them. Some of the tunes were evidently sold outright to the entertainers, and he received no credit for them. Harry also acted on stage from time to time, an experience that would be useful to him when plugging his songs in later years. Even though he had shortened the family name to Gumm it did not suit him, and at some point in his teens he changed it to a derivative of his mother's maiden name, adding "Von" to Tilzer to make it fancier. His brother Albert followed that example some point in the 1890s, and once the pair became famous, brothers Jules, Jacob (Jack) and Will also changed their names to Von Tilzer, although Will was published as Gumm through around 1912.

After a few years on the road, and with many songs under his belt, Harry finally had one published. Titled I Love You Both it did not fare too well, and he earned practically nothing from it. Still, popular vaudevillian performer Lottie Gilson encouraged him and let him know that his talents were viable. At her prompting Harry moved permanently to New York City at age 20, with just $1.65 in his pocket, and started playing in a local saloons for an average of $15.00 per week. He hit the road again for a short time with a traveling medicine show, but again landed in New York, working in saloons and as a Vaudeville accompanist and singer. He kept writing songs, but they were again sold outright to entertainers, usually for $2.00 each. Some were reportedly even bought by famous theater owner Tony Pastor for his shows, but no credit was given to Harry, a common practice of that time. He worked for a time with entertainer George Sidney doing what is described as "Dutch" comedy act.

The Big Breaks

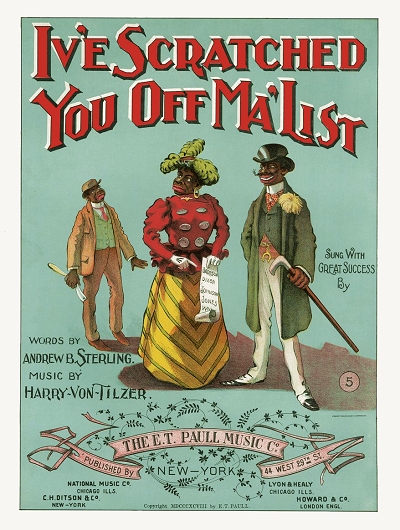

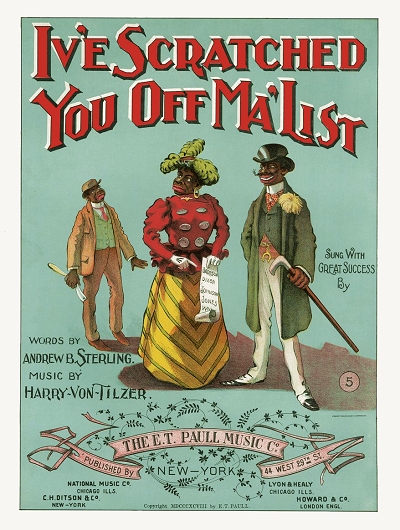

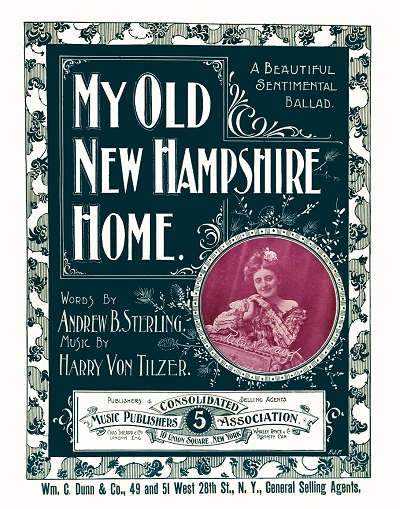

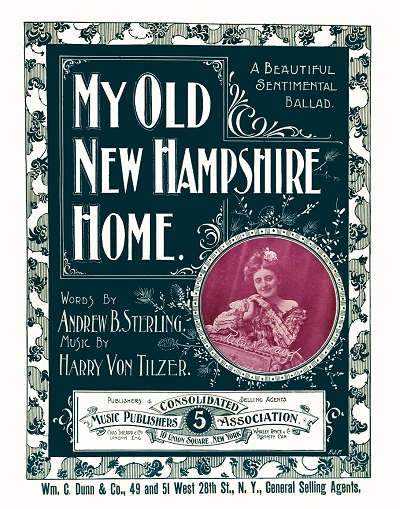

In 1896 Harry met another songwriter, Andrew B. Sterling. They ended up rooming together in the shadow of the Brooklyn Bridge, and started collaborating on songs. They were able to sell a couple of their early ethnic efforts to publishers, including I've Scratched You Off Ma' List to E.T. Paull in 1897, shortly after he set up business there. I'll Be a Sister to You and My Pretty Polly were also published by Paull in 1898. But no hits were forthcoming. It was the threat of eviction in 1898 that pushed the pair to quickly compose My Old New Hampshire Home and take it around to publishers. After more rejections, it was finally purchased by William Dunn of the Orphean Music Company for $5.00 in advance, and a final sale of an additional $10.00. The song ended up selling over two million copies in the next decade, which would have made the publisher wealthy, but not the writers, another common story of that time. A recording of the piece that same year also became quickly popular. Still, the brisk sales of the piece encouraged Harry and Andrew to keep plugging away. Another fortuitous circumstance also gave him a break, and shifted the income from this song back in his direction.

They were able to sell a couple of their early ethnic efforts to publishers, including I've Scratched You Off Ma' List to E.T. Paull in 1897, shortly after he set up business there. I'll Be a Sister to You and My Pretty Polly were also published by Paull in 1898. But no hits were forthcoming. It was the threat of eviction in 1898 that pushed the pair to quickly compose My Old New Hampshire Home and take it around to publishers. After more rejections, it was finally purchased by William Dunn of the Orphean Music Company for $5.00 in advance, and a final sale of an additional $10.00. The song ended up selling over two million copies in the next decade, which would have made the publisher wealthy, but not the writers, another common story of that time. A recording of the piece that same year also became quickly popular. Still, the brisk sales of the piece encouraged Harry and Andrew to keep plugging away. Another fortuitous circumstance also gave him a break, and shifted the income from this song back in his direction.

They were able to sell a couple of their early ethnic efforts to publishers, including I've Scratched You Off Ma' List to E.T. Paull in 1897, shortly after he set up business there. I'll Be a Sister to You and My Pretty Polly were also published by Paull in 1898. But no hits were forthcoming. It was the threat of eviction in 1898 that pushed the pair to quickly compose My Old New Hampshire Home and take it around to publishers. After more rejections, it was finally purchased by William Dunn of the Orphean Music Company for $5.00 in advance, and a final sale of an additional $10.00. The song ended up selling over two million copies in the next decade, which would have made the publisher wealthy, but not the writers, another common story of that time. A recording of the piece that same year also became quickly popular. Still, the brisk sales of the piece encouraged Harry and Andrew to keep plugging away. Another fortuitous circumstance also gave him a break, and shifted the income from this song back in his direction.

They were able to sell a couple of their early ethnic efforts to publishers, including I've Scratched You Off Ma' List to E.T. Paull in 1897, shortly after he set up business there. I'll Be a Sister to You and My Pretty Polly were also published by Paull in 1898. But no hits were forthcoming. It was the threat of eviction in 1898 that pushed the pair to quickly compose My Old New Hampshire Home and take it around to publishers. After more rejections, it was finally purchased by William Dunn of the Orphean Music Company for $5.00 in advance, and a final sale of an additional $10.00. The song ended up selling over two million copies in the next decade, which would have made the publisher wealthy, but not the writers, another common story of that time. A recording of the piece that same year also became quickly popular. Still, the brisk sales of the piece encouraged Harry and Andrew to keep plugging away. Another fortuitous circumstance also gave him a break, and shifted the income from this song back in his direction.A few months after the sale of My Old New Hampshire Home and a few other pieces to other New York publishers, the Orphean catalog was purchased by Maurice Shapiro and Louis Bernstein, incorporated into their firm of Shapiro and Bernstein, Co., which exists still into the 21st century in spite of a number of changes in its lifetime. One of those changes involved seeing the potential of Von Tilzer as both a composer and recognizable name. His Vaudeville reputation also preceded him, giving Harry more salability. So after convincing him to quit the stage and hiring him as a staff composer they offered Von Tilzer and Sterling a considerable royalty of $4,000 on the piece they had sold for $15. In order to keep Von Tilzer around writing more hits, and they saw that more were coming, they also put him on the banner as a partner in the firm. Harry and Andrew did not disappoint, and soon came up with I'd Leave Ma Happy Home For You in 1899, a Vaudeville sensation. Other songs with their names also sold well.

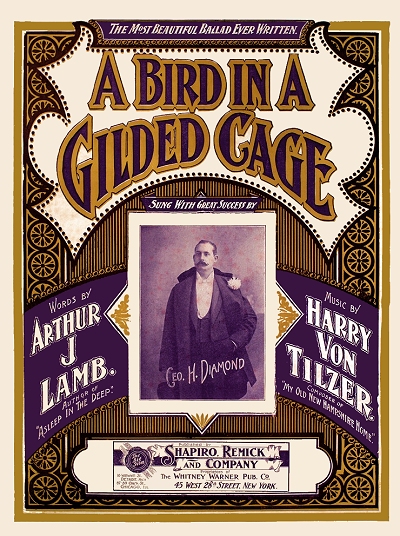

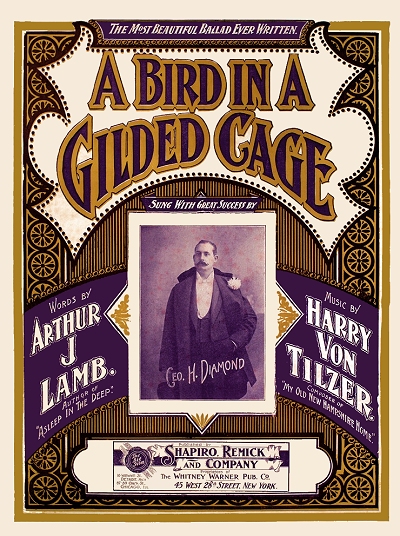

However, Harry branched out and tried out some lyrics given to him by another rising star, Arthur J. Lamb, who was more of sentimental ballad writer than a comic one. In 1900, it was clear that A Bird in a Gilded Cage would be a lasting maudlin tear jerker. The ballad of a woman held prisoner by her choice to marry for money, it was Harry that insisted on the girl actually being married to the old man instead of just a kept woman living in sin, a wise decision given the moral climate of the time. When working out the melody at a party, some of the girls within earshot heard the revised lyrics and were driven to tears, giving Harry a clue that Lamb had workable talent. They would write many other "tear jerkers" together over the next several years.

a wise decision given the moral climate of the time. When working out the melody at a party, some of the girls within earshot heard the revised lyrics and were driven to tears, giving Harry a clue that Lamb had workable talent. They would write many other "tear jerkers" together over the next several years.

a wise decision given the moral climate of the time. When working out the melody at a party, some of the girls within earshot heard the revised lyrics and were driven to tears, giving Harry a clue that Lamb had workable talent. They would write many other "tear jerkers" together over the next several years.

a wise decision given the moral climate of the time. When working out the melody at a party, some of the girls within earshot heard the revised lyrics and were driven to tears, giving Harry a clue that Lamb had workable talent. They would write many other "tear jerkers" together over the next several years.Another bonus for the family, Harry's brother Albert was hired as a manager in the Chicago branch of Shapiro, Bernstein and Von Tilzer. As of the 1900 census Harry was listed as a musician and composer, and Albert was in Chicago similarly listed as a music composer. Soon after that, Albert left the Chicago position for New York where he went back to selling shoes for a short time. Harry gave his brother a boost by publishing Albert's Absent-Minded Beggar Waltzes, which while not a great hit did give Albert some circulation in Manhattan and a moral boost. With his new found spending money, Harry started to take up hobbies, among them being harness racing. As noted in The Music Trade Review of June 1, 1901: "Harry Von Tilzer has had several smart brushes on the Speedway with his 2.10 trotter, and generally holds his own. He is an expert driver and it is to be expected that he will become quite a light in the trotting world."

In league with Lamb and Sterling, Harry managed to turn out a number of successful tearjerkers and popular tunes over the next two years. He also was one of the first to produce a dance folio, a book that consisted of instrumental arrangements of popular songs. These were a blessing to pianists everywhere who did not need the words as much as they did the music, and the cost of a folio was considerably less than that of the 40 or so individual tunes contained within. What soon became clear, if not to Harry but to others, is that he was great at creating memorable melodies for lyrics of all varieties, but not so much at plain old instrumentals like marches, and certainly not rags. A handful of his songs were packaged as instrumentals as well, but the songs generally sold better in spite of their being more simply scored. In any case, he was grateful to his partners for the opportunity they had provided, but frustrated as well since he wanted more control over the end product, and more profit as well. To that end, he took his wealth of short term experience as a partner in a publishing firm, and at the beginning of 1902 created his own company under his own name, the Harry Von Tilzer Music Company. The parting of ways was reportedly amicable as Von Tilzer was glad for the start they had given him.

Moving Forward - And Backwards

The evidence that having his own company to put out his product was a beneficial move is in the number of tunes that suddenly sprang forth from Harry and his lyricists in 1902, nearly five times that in 1901. Some of his other new tunes may have been holdovers from the previous year as well. To boost his new catalog he also purchased the catalog of Mullen & Cain of Worcester, Massachusetts, who were leaving the business. One of Harry's new partners was Vincent Bryan who proved himself quite capable with many composers over the next 20 years. Bryan and Von Tilzer came up with Down Where the Wurzberger Flows, a love song to beer in some respects, which saw popularity through singer Nora Bayes. He would follow this up with the clever Under the Anheuser Bush with Sterling.

Some of his other new tunes may have been holdovers from the previous year as well. To boost his new catalog he also purchased the catalog of Mullen & Cain of Worcester, Massachusetts, who were leaving the business. One of Harry's new partners was Vincent Bryan who proved himself quite capable with many composers over the next 20 years. Bryan and Von Tilzer came up with Down Where the Wurzberger Flows, a love song to beer in some respects, which saw popularity through singer Nora Bayes. He would follow this up with the clever Under the Anheuser Bush with Sterling.

Some of his other new tunes may have been holdovers from the previous year as well. To boost his new catalog he also purchased the catalog of Mullen & Cain of Worcester, Massachusetts, who were leaving the business. One of Harry's new partners was Vincent Bryan who proved himself quite capable with many composers over the next 20 years. Bryan and Von Tilzer came up with Down Where the Wurzberger Flows, a love song to beer in some respects, which saw popularity through singer Nora Bayes. He would follow this up with the clever Under the Anheuser Bush with Sterling.

Some of his other new tunes may have been holdovers from the previous year as well. To boost his new catalog he also purchased the catalog of Mullen & Cain of Worcester, Massachusetts, who were leaving the business. One of Harry's new partners was Vincent Bryan who proved himself quite capable with many composers over the next 20 years. Bryan and Von Tilzer came up with Down Where the Wurzberger Flows, a love song to beer in some respects, which saw popularity through singer Nora Bayes. He would follow this up with the clever Under the Anheuser Bush with Sterling.Other partners included George Totten Smith and Eddie Moran who would write for many years with Harry. Lamb continued to provide him with the sad and maudlin ballads, and Harry complied with more stirring melodies such as The Banquet in Misery Hall and The Mansion of Aching Hearts, one of the songs Irving Berlin was hired to promote while still a few years off from being a composer in his own right. So he had a variety of lyric types to choose from. The firm expanded quickly, and two months after forming he moved to a large headquarters at 42 West 28th Street, two doors down from one of the publishers that helped him get his footing, E.T. Paull. Hoping to help with the delegation of authority within his new company, Harry sent for his brother Albert in Chicago, who became a manager for a couple of years before moving off into his own firm.

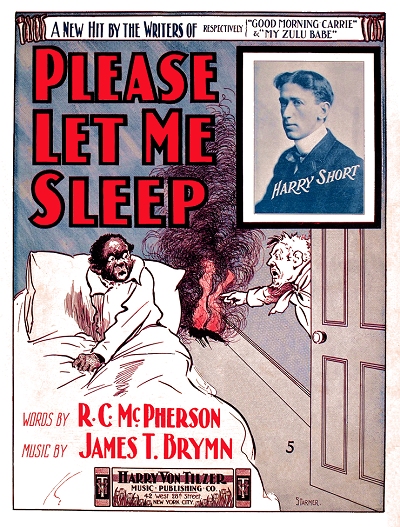

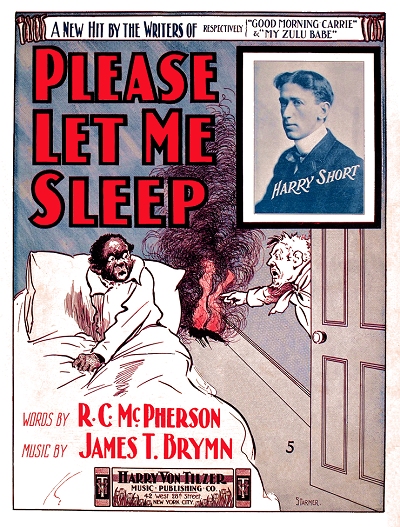

In order to get his firm known, just as much as his compositions, Harry was active in pursuing new writers, new sellers, and the public. One of his most famous promotional stunts underscores his technique, as noted in an unsigned but obvious article that he placed in a newspaper. He was trying to sell what he was sure would be a hit, even though it was not his own composition. In full cooperation of the management, who likely got a cut of lobby sales, Von Tilzer himself posed as an audience member at a rooftop garden theater. He kept "falling asleep" and snoring loudly, creating disruption. His wife, who was not in on the gag, was quite embarrassed, and kept kicking him "awake" under the table. After a little time passed and many complaints were forwarded to the management, a waiter came to the table to remove the disruptive faker. As he was literally dragged to the elevator Von Tilzer, who had started his career as a singer, lit into the chorus: "Please go 'way and let me sleep, don't disturb my slumber deep." On cue, the female singer on the stage continued the song with the orchestra, and the audience erupted into favorable laughter having been taken for a ride by the former stage actor and singer. But more importantly, that evening and the next day, copies of the piece all but disappeared in exchange for their mad money. It also became a Vaudeville standard, used for comic effect for sleeping actors or audience plants. Black composers James Tim Brymn and Richard C. McPherson certainly gained notoriety from their generous benefactor. His success in plugging such songs was enough that Harry was able to buy his own building at 27 West 28th Street in early 1903.

Harry soon found another area that in spite of his considerable talent was not a good fit. That was Broadway. Having evolved from Vaudeville and more legitimate theater, Broadway shows usually consisted of a hybrid of some semblance of a play mixed with some semblance of popular songs - often in no way related to the plot, but thrown in just the same to create a musical experience. This was different from the trend of operettas, or light popular opera, such as those of Victor Herbert. George M. Cohan was gaining much success in 1903-1904 with his musical plays, and others were trying to find their way. Von Tilzer tried, but ultimately lost his way. Some of his pieces had already been interpolated into shows, so it seemed easy. Plot was not so easy, however, and may have been the downfall of his early attempts.

such as those of Victor Herbert. George M. Cohan was gaining much success in 1903-1904 with his musical plays, and others were trying to find their way. Von Tilzer tried, but ultimately lost his way. Some of his pieces had already been interpolated into shows, so it seemed easy. Plot was not so easy, however, and may have been the downfall of his early attempts.

such as those of Victor Herbert. George M. Cohan was gaining much success in 1903-1904 with his musical plays, and others were trying to find their way. Von Tilzer tried, but ultimately lost his way. Some of his pieces had already been interpolated into shows, so it seemed easy. Plot was not so easy, however, and may have been the downfall of his early attempts.

such as those of Victor Herbert. George M. Cohan was gaining much success in 1903-1904 with his musical plays, and others were trying to find their way. Von Tilzer tried, but ultimately lost his way. Some of his pieces had already been interpolated into shows, so it seemed easy. Plot was not so easy, however, and may have been the downfall of his early attempts.One early effort composed with Sterling was titled Tiddle-De-Winks which did not even make it out of Boston after its premiere in late 1902. The next was The Fisher Maiden, composed with Lamb, which debuted and died in just one month in 1903, lasting only 34 performances, and losing around $40,000. As had been hinted at when the show closed, late in 1904 a retooled version of the same play variously titled The Miller's Daughter or The Jolly Baron, with additional songs composed with Addison Burkhardt and Aaron Hoffman tried to revive the story. It was only half as successful, going for a mere 16 performances before shutting down forever. Another short lived effort that didn't even make it to Broadway was Heigh Ho in 1905. It would be several years before Von Tilzer would attempt to stage something again. With his health failing from the stress, Harry retreated to Bermuda for several weeks to recover in early 1905.

Going back to song writing and publishing, Harry managed to turn out hits both by himself and other composers, and was soon one of the top firms in Tin Pan Alley and Manhattan, eventually rivaled by Jerome H. Remick, Ted Snyder and Irving Berlin in the popular music field. His own hits included the comic Alexander, Don't You Love Your Baby No More?, Hannah Won't You Open the Door, Wait Till the Sun Shines, Nellie, and the catchy and soon ubiquitous Rufus Rastus Johnson Brown, What You Goin' To Do When The Rent Comes 'Round?. Alexander eventually served as a bit of a prototype for Berlin's Alexander's Ragtime Band several years later.

As with some of his earliest pieces, many of these were "coon" songs, but refined to be less offensive than the previous offerings, allowing a more genteel sector of public to perform them with fewer reservations about the content. He also continued to plant himself or some of his hired promoters in public venues to promote the latest wannabe hits with help from the management (likely including a cut for them). Von Tilzer soon had hired promoter Ben Bornstein who became the firm's professional manager for nearly two decades. Harry has also been regarded as one of the originators of the system of song plugging, placing pieces in shows and making sure of surprise public performances.

There is a legend, one that has been hard to substantiate as absolute fact, that Harry was in part responsible for the very name "Tin Pan Alley." According to writer Monroe Rosenfeld, he had visited Von Tilzer's office and heard his piano, which allegedly had sheets of paper or the like in the strings, giving it a tinny sound. Harry's pianos, combined collectively with those of the other publishing firms lining 28th Street between Broadway and Fifth Avenue, combined to make a clattering like the cacophony of tin pans being beat on. Thus Rosenfeld coined the phrase and it quickly became popular, but its true origin is lost to legend.

By this time, Albert had left the firm to manage the York Music Company. The cause of the break between the brothers is uncertain. However, it was made rather public in mid-1905 when Albert printed advertisements in the New York Clipper and other papers including the announcement, "Having severed my connections with the HARRY VON TILZER MUSIC PUB.CO., I beg to announce to all my friends that I shall be pleased to hear from them, either personally or by mail, at my new place of business." Just the same they would remain on sometimes tenuous but otherwise friendly terms, and even share lyricists and writers for nearly the next two decades. Jack had also parted ways with his brother in late 1904, working as a business manager around Tin Pan Alley for a while, but ultimately hooking up with Albert. In 1906, Harry married his New York born wife Ida Rosenberg, also of German/Polish parents. She had been previously married and subsequently widowed, left with a substantial fortune. Ida brought her daughter along with her into Harry's home.

However, it was made rather public in mid-1905 when Albert printed advertisements in the New York Clipper and other papers including the announcement, "Having severed my connections with the HARRY VON TILZER MUSIC PUB.CO., I beg to announce to all my friends that I shall be pleased to hear from them, either personally or by mail, at my new place of business." Just the same they would remain on sometimes tenuous but otherwise friendly terms, and even share lyricists and writers for nearly the next two decades. Jack had also parted ways with his brother in late 1904, working as a business manager around Tin Pan Alley for a while, but ultimately hooking up with Albert. In 1906, Harry married his New York born wife Ida Rosenberg, also of German/Polish parents. She had been previously married and subsequently widowed, left with a substantial fortune. Ida brought her daughter along with her into Harry's home.

However, it was made rather public in mid-1905 when Albert printed advertisements in the New York Clipper and other papers including the announcement, "Having severed my connections with the HARRY VON TILZER MUSIC PUB.CO., I beg to announce to all my friends that I shall be pleased to hear from them, either personally or by mail, at my new place of business." Just the same they would remain on sometimes tenuous but otherwise friendly terms, and even share lyricists and writers for nearly the next two decades. Jack had also parted ways with his brother in late 1904, working as a business manager around Tin Pan Alley for a while, but ultimately hooking up with Albert. In 1906, Harry married his New York born wife Ida Rosenberg, also of German/Polish parents. She had been previously married and subsequently widowed, left with a substantial fortune. Ida brought her daughter along with her into Harry's home.

However, it was made rather public in mid-1905 when Albert printed advertisements in the New York Clipper and other papers including the announcement, "Having severed my connections with the HARRY VON TILZER MUSIC PUB.CO., I beg to announce to all my friends that I shall be pleased to hear from them, either personally or by mail, at my new place of business." Just the same they would remain on sometimes tenuous but otherwise friendly terms, and even share lyricists and writers for nearly the next two decades. Jack had also parted ways with his brother in late 1904, working as a business manager around Tin Pan Alley for a while, but ultimately hooking up with Albert. In 1906, Harry married his New York born wife Ida Rosenberg, also of German/Polish parents. She had been previously married and subsequently widowed, left with a substantial fortune. Ida brought her daughter along with her into Harry's home.Harry's songs started to make the rounds internationally, and one of them was even readily adaptable for other continents. Take Me Back to New York Town was also heard as Take Me Back to London Town in England and Take Me Back to Melbourne Town in Australia. In March 1905 Harry ventured to Europe and England for several months to secure arrangements for overseas distributions through his former partner Maurice Shapiro. Most of his writing with Lamb had ceased by this time, as the lyricist started working more with Albert Von Tilzer. His primary partner from 1906 to 1909 was Vincent Bryan, although he was doing some work also with Will Dillon and Jack Mahoney, also writing partners with Albert. As a publisher, he had the ignominious distinction of having rebuffed the pleas of Max Brooks, who had come to Harry on behalf of his young singing waiter friend Irving Berlin, to give the immigrant composer a chance at a position writing or at least promoting songs. How different his firm might have been with Berlin on board.

One of Harry's enduring hits of 1909 with Bryan was The Cubanola Glide, an easy dance tune that succeeded in both song and instrumental form. His single tune with Jimmy Lucas, I Love I Love I Love My Wife (But Oh! You Kid!), once again proved his capabilities as both writer and promoter. Now having followed the general migration of publishers from 28th Street to the Broadway district, moving to 125 West 43rd Street near the heart of the Broadway district, Harry made one more attempt at staging a Broadway show in 1909 with The Kissing Girl. As with the other four, the curtain fell on it with a thud in short order, and he backed down from further attempts. The publisher is shown in the 1910 census as residing at the Hotel Carlton with Ida, listed first and foremost as a music composer rather than as a boss.

Boom Time and Down Time

As the 1910s started, 28th Street had been all but abandoned by the bulk of publishers that had populated that storied street for over a decade. Von Tilzer now occupied a four story building that nearly backed up to that of fellow publisher E.T. Paull on 42nd Street. He had it remodeled to handle a growing staff, including a grand store at street level. The professional department, charged with promoting songs to the industry, also expanded to nearly an entire floor. His brother, Will, was still working for him during the move. He would leave the firm in early 1913 to form the Broadway Music Company. However, before that time Will proved some of his business acumen that such an asset to Harry in an article in the Music Trade Review on November 4, 1911, concerning the spending of money on songs:

More money is squandered in the popular music publishing field than in any other well established line in existence. It is a well-known fact to people at all familiar with the music publishing business, that there are great money making possibilities in the possession of what is called a "hit," but how many publishers really make money when they get a hit? Not many. The majority turn right around and sink the profits from a successful number into a hoped-for hit.

It is a well-known fact to people at all familiar with the music publishing business, that there are great money making possibilities in the possession of what is called a "hit," but how many publishers really make money when they get a hit? Not many. The majority turn right around and sink the profits from a successful number into a hoped-for hit.

It is a well-known fact to people at all familiar with the music publishing business, that there are great money making possibilities in the possession of what is called a "hit," but how many publishers really make money when they get a hit? Not many. The majority turn right around and sink the profits from a successful number into a hoped-for hit.

It is a well-known fact to people at all familiar with the music publishing business, that there are great money making possibilities in the possession of what is called a "hit," but how many publishers really make money when they get a hit? Not many. The majority turn right around and sink the profits from a successful number into a hoped-for hit.The great mistake made almost invariably, is to invest money as well as energy in a bad number, thinking it to be the combination that turns out a so-called hit. If you have watched the business closely, you will have observed (if you are honest with yourself) that successful numbers during the past number of years, were hits before they were published. In other words, they possessed unusual merit in themselves and would have been just as successful if plenty of energy had been used and if the money had not been so much in evidence.

To verify the above, the writer wishes to quote as examples the following songs published within the past two or three years : "The Cubanola Glide," "Don't Take Me Home," "I Remember You," "I Love My Wife, but Oh You Kid," "Under the Yum Yum Tree," "I Love It," "Lovie Joe," "All Alone," and many other numbers of lesser size. "All Aboard for Blanket Bay," our present big ballad hit is taking twice as long to make as it would if we squandered money on it. But how do we benefit by exercising judgment and patience? The answer is that it will live twice as long and when we balance our books in the end, we will find that we have made money, not lost it! "Blanket Bay" has been out since the first of January, 1911. To-day it is bigger with both the profession and the trade than ever before, and it is going along at a rate that is astonishing.

"I Want a Girl Just Like the Girl that Married Dear Old Dad," a song we published hardly three months ago, is already acknowledged by everyone, including competitors, to be the most promising song of the year. "They Always Pick on Me," and "Knock Wood" will also be called hits before the season is many months older.

We have had more real hits in the past three years than ever before. What is more important, we have made more money. The last statement takes on extra weight when you consider the small margin of profit to-day. Merit always wins out.

The hits came out of the house of Von Tilzer in increasing quantities during the 1910s, including many from Harry himself. After some time apart, Sterling came back into the fold and contributed once again to some memorable tunes. Their first was the lovely sleepy little child tune All Aboard For Blanket Bay. It was with Dillon that he came up with another unforgettable hit that has lasted a century to date, I Want a Girl (Just Like the Girl that Married Dear Old Dad), and another that still exists in thousands of copies that live in piano benches around the country, All Alone. The former was one of the firm's best sellers of 1912, contributing to record sales on January 2 of that year. The latter was a great boon for the telephone, suggesting phone romances and perhaps hinting at more in a not-too-subtle suggestive manner.

Even good publishers and good managers can sometimes make poor decisions of the moment. Such had already been done with Irving Berlin. But Harry also nearly nixed one of the most enduring songs of the century, which was fortunately saved by alcohol. Joseph McCarthy and James V. Monaco had written some tunes together, and brought a ragtime one step to Von Tilzer which he subsequently rejected. One of the firm's song pluggers, Nemo Roth, was a friend of the composers. While it was his job to promote Von Tilzer tunes at events like dance contests, he sometimes knew enough to take a chance. Roth was at a Brooklyn dance event one evening prepared to sing Am I In Love, but Monaco and McCarthy asked if he would try their tune instead. The singer had been downing large quantities of beer that evening, and by the time he got up to perform his pace had slowed considerably. As a result, he had to sing the piece You Made Me Love You at a much slower pace, instantly (if accidentally) transforming a ragtime song into a tear-jerker of a ballad. Even though Harry, who was present, was clearly irritated by the substitution, by the end of the performance he acknowledged that was a tune with great possibilities. The following week he presented it to his friend Al Jolson at the Winter Garden Theater, and after its performance the singer was called back to stage over a dozen times. Ironically, it was Will who ended up publishing the piece under his Broadway Music imprint.

The following week he presented it to his friend Al Jolson at the Winter Garden Theater, and after its performance the singer was called back to stage over a dozen times. Ironically, it was Will who ended up publishing the piece under his Broadway Music imprint.

The following week he presented it to his friend Al Jolson at the Winter Garden Theater, and after its performance the singer was called back to stage over a dozen times. Ironically, it was Will who ended up publishing the piece under his Broadway Music imprint.

The following week he presented it to his friend Al Jolson at the Winter Garden Theater, and after its performance the singer was called back to stage over a dozen times. Ironically, it was Will who ended up publishing the piece under his Broadway Music imprint.With Sterling he created a musical monster with The Ragtime Goblin Man in 1912. Lots of ballads flowed from the team of Von Tilzer and Sterling in 1913, with the biggest being When It's Cotton Blossom Time (Sweet Rosalie). In 1914 Harry and his firm capitalized on the Tango craze, hitting it from several angles. They also covered all of the dances being made popular by the team of Vernon and Irene Castle with their fast-selling You Can Tango You Can Trot Dear But Be Sure And Hesitate, the last part referring to a popular waltz form of the time. This same year, Harry and his brother Albert became charters member of the newly formed American Society of Composers, Authors and Publishers (ASCAP), an important organization that continues to protect the rights of the music business into the 21st century.

Having been published for some 20 years by the mid-1910s, and having been in business for well over a decade, Harry began to slow, but certainly not halt his writing activities, concentrating more on the business end for a while as the sheet music market became more competitive. He still performed his songs on a semi-regular basis in vaudeville houses around the East, mostly in New York City, and sometimes as a headliner on the Keith circuit. These even included performances at the famed Palace Theater, the top vaudeville house in the country.

Van Tilzer's ego and instinct both seemed to be intact, as noted in his own words published in January, 1915:

The public wants pictures and problems of everyday life. It wants simplicity. The old-style melodrama was loaded with ideas. It was a kaleidoscope of scenes and situations. A play should contain but one or two good ideas worked out with truth and logic. The time has passed when the public wants a sop thrown to it. It does not demand a happy ending so that it may go home and sleep in peace. The public is willing to think nowadays. The ethics of the drama are undergoing change, as is everything else. If I haven't learned the public taste in twenty-five years of song writing, music publishing, story building, acting, journalism, traveling, studying human nature , all the things I've done and all the things I've seen, then nobody'll ever learn it. I believe I can pick winners. I've certainly picked one, and I've got another up my sleeve. A million's waiting for the man who picks the winning play.

In 1916 the firm picked up and moved north to an even larger building at 222 West 46th Street, where many other publishers had relocated as well. Harry picked up a couple of new prolific partners, who with Sterling would help him through World War One and into the twenties. They were Garfield Kilgour and the clever Lou Klein. While the war was actually easy to conquer musically, as patriotic songs about "our boys over there" sold no matter what, he had another obstacle faced by many older ragtime-era musicians and composers, the onslaught of jazz in 1917.

Even though Von Tilzer was a charter member of ASCAP, he became frustrated with that organization within three years, and made news when he resigned from in in October, 1917. According to the New York Clipper of October 31, he said:

I do not feel that the society will ever do me any good. It may be a wonderful thing for some publishers, but as far as I am concerned, I believe that by the time the various officials and staff of the organization are paid there will be nothing left for me. I am essentially a publisher of popular music, and I feel that it is absolutely necessary that my compositions be featured in every place where music is performed, and I believe that if the director of an orchestra pays the price of the published orchestration, that is all I can really expect... So you see that while I am receiving nothing from the society, I am losing business by remaining in it, which is the reason I have decided to resign.

In later years Harry was readmitted once he found that the system was working much better. Just prior to this Von Tilzer publicly celebrated the 25th anniversary of his sole 1892 composition, expanding the theme by claiming to have been fully engaged in the business for a quarter century, in spite of his earlier thin output.

In later years Harry was readmitted once he found that the system was working much better. Just prior to this Von Tilzer publicly celebrated the 25th anniversary of his sole 1892 composition, expanding the theme by claiming to have been fully engaged in the business for a quarter century, in spite of his earlier thin output.As the war business wound down in 1919 the output from the Von Tilzer company started to look depleted as well. They moved once again, this time to 1658 Broadway, not far from the 46th Street address. Sterling still made some bold contributions to the team and to the company, but by this time they were just writing new songs that sounded old in many cases. However, he did manage one more substantial hit for Sophie Tucker, Old King Tut, playing upon the popularity of the recently discovered boy king's tomb. Harry also tried for Broadway again, this time composing the musical Mad Love with Frances Nordstrom. It never made it far beyond the manuscript stage, and was never produced, even though there were plans for it around the Christmas holidays in 1919. Several contracts remain between Nordstrom and Von Tilzer with producer Lew Fields through 1920, but no production is known to have taken place.

A judgment was levied against Harry in 1920 in favor of actress Jean Newcomb, possibly for non-payment of salary. During his appeal with the New York Supreme Court, Harry revealed that his salary was only $25 per week from his company, and that it was his only source of income, so he was unable to pay the $3,173 judgment. He made it clear that his wife, Ida, owned the stock that had formerly belonged to him. When questioned about a statement he had made that he "had been very fortunate financially," Von Tilzer clarified that it was his firm that had been fortunate, but that he was still relatively financially bereft. This was a questionable convenience, but one that held up just the same, resulting in a reduced judgment.

Jules Von Tilzer also made it into the news around that same time. He was allegedly stabbed by his wife, Estelle, as he lay sleeping one night in late February 1920. Estelle's story was a bit different. She had reacted to a telephone call from a mysterious woman who alerted her that Jules had been fooling around with another woman for some three years. When confronted with that news, the 225 pound Jules denied the allegation and reportedly jumped out of bed. The 90 pound Estelle grabbed a knife in self-defense. Neither of them seemed to be able to recall how the knife entered his body. It was not favorable publicity for Harry, who was also mentioned in the articles on the incident as being the brother of Jules. To compound things, his longtime professional manager, Ben Bornstein, left the firm in 1922. However, he did add composer Ted Barron to the staff that same month.

Late in 1922 Von Tilzer was offered another stint in vaudeville as a feature performer. He went back on the road only briefly, but by 1923, Harry was all but retired. His company went into receivership and was downsized, moving this time to 719 Seventh Avenue. The bankruptcy notices cited liabilities of $35,863, with unbalanced assets of only $3,902. Among the creditors were the print jobber Robert Teller & Son & Dorner for a whopping $12,113, former manager Ben Bornstein for $3,000, and his brother Will for $1,000. However, amends were made and Von Tilzer had reorganized by the end of the year, moving again to moderately larger quarters at 1587 Broadway.

After partially disappearing from view for a while, the old performer in Harry decided to try and make a mark again. In the summer of 1929 he dusted off an old plot, Heigh Ho, and fit new songs into it. The revived musical opened in Asbury Park, New Jersey on August 19, with a promise of opening at the Royale in Manhattan three weeks later. Sadly, in spite enthusiastic reports from the trade, it died in New Jersey, and Harry was done with Broadway for good.

Harry appeared with Ida in both the 1920 and 1930 census records, living in Manhattan, both times listed as a composer and music publisher. The couple also had a home in Freeport on Long Island where they were spending more time. Ida Von Tilzer died in Freeport, Long Island on September 25, 1930 after a five month illness. He became a little crustier in his attitude after this, and in the early 1930s commented on contemporary composers and the consumers, saying that "all people like today are mush love songs that don't have much story to them." He then referred back to such songs as Wait Till the Sun Shines Nellie and When the Harvest Days are Over, Jessie Dear, which had a story line to them. A later article in the Christian Science Monitor in 1946 had a markedly different take on trends, with the author claiming that "Tin Pan Alley... never turned out very good music, and its lyrics were usually over-sentimental. But the product of such song writers as Gus Edwards, Charles K. Harris and Harry Von Tilzer was usually wholesome and singable stuff."

Ida Von Tilzer died in Freeport, Long Island on September 25, 1930 after a five month illness. He became a little crustier in his attitude after this, and in the early 1930s commented on contemporary composers and the consumers, saying that "all people like today are mush love songs that don't have much story to them." He then referred back to such songs as Wait Till the Sun Shines Nellie and When the Harvest Days are Over, Jessie Dear, which had a story line to them. A later article in the Christian Science Monitor in 1946 had a markedly different take on trends, with the author claiming that "Tin Pan Alley... never turned out very good music, and its lyrics were usually over-sentimental. But the product of such song writers as Gus Edwards, Charles K. Harris and Harry Von Tilzer was usually wholesome and singable stuff."

Ida Von Tilzer died in Freeport, Long Island on September 25, 1930 after a five month illness. He became a little crustier in his attitude after this, and in the early 1930s commented on contemporary composers and the consumers, saying that "all people like today are mush love songs that don't have much story to them." He then referred back to such songs as Wait Till the Sun Shines Nellie and When the Harvest Days are Over, Jessie Dear, which had a story line to them. A later article in the Christian Science Monitor in 1946 had a markedly different take on trends, with the author claiming that "Tin Pan Alley... never turned out very good music, and its lyrics were usually over-sentimental. But the product of such song writers as Gus Edwards, Charles K. Harris and Harry Von Tilzer was usually wholesome and singable stuff."

Ida Von Tilzer died in Freeport, Long Island on September 25, 1930 after a five month illness. He became a little crustier in his attitude after this, and in the early 1930s commented on contemporary composers and the consumers, saying that "all people like today are mush love songs that don't have much story to them." He then referred back to such songs as Wait Till the Sun Shines Nellie and When the Harvest Days are Over, Jessie Dear, which had a story line to them. A later article in the Christian Science Monitor in 1946 had a markedly different take on trends, with the author claiming that "Tin Pan Alley... never turned out very good music, and its lyrics were usually over-sentimental. But the product of such song writers as Gus Edwards, Charles K. Harris and Harry Von Tilzer was usually wholesome and singable stuff."The Von Tilzer firm continued on into the 1930s, and publishing was still somewhat of a family business. Albert, still actively composing, had long since run through the life of his York Music Company with Jack. Broadway Music Publishing Company run by Will was still going strong, and brother H. Harold Gumm was acting as an attorney for all of the brothers as the need arose. There was a spurt of songs composed in 1935 with Moran, potentially intended for use in motion pictures, but nothing definitive has surfaced on this.

In June 1937 Harry was involved in an automobile crash, hitting another car and then a tree. He received severe head injuries that kept him from his duties for a few weeks as he recovered. Once he returned to work it was clear that his pace had slowed down a bit. The Ragtime Goblin Man came back in 1941 with Von Tilzer and Sterling's unsuccessful The Swing-Time Boogie-Boo Man. Harry wrote one last piece, this time with his brother Albert, in 1943, Sierra Moonlight, and then faded away into the woodwork as his firm was sold off.

Von Tilzer spent the last years of his life at the Hotel Woodward in Manhattan, finally passing on in early 1946. But he will not and cannot be forgotten as his work remains a part of the fabric of popular song in the United States, and even the world. The catalog floundered for a while, but was purchased from the heirs by bandleader Lawrence Welk in 1958. He saw to it that many of the great Von Tilzer tunes were not only featured on his weekly television show and concert tours, that that they were once again available in print.

Harry Von Tilzer didn't have the biggest hits or the most quantity, but he helped originate some of the paradigms of the business, and certainly made it competitive in a healthy sense for many decades. In 1970 Harry Von Tilzer and his brother Albert were both inducted into the Songwriter's Hall of Fame, but both had already won fame with fans of old-time songs around the world.