One of the lesser-regarded composers of the ragtime era by some historians, Joe Jordan may not have had the later prominence of Scott Joplin or Eubie Blake, but he still had the influence of them, and during his lifetime was certainly more successful in many regards than Joplin. In fact, some have equated Jordan's musical life as the one that Joplin should have had but was not able to achieve. While some of his efforts were actually made famous by other performers, he still needs to be regarded as both musician and entrepreneur, having lived a long and adventurous life full of notable milestones.

Becoming a Musician of Note - Saint Louis

Born in the musically rich environment of Cincinnati, Ohio in 1882 to Zachariah Taylor Jordan and Josephine Ross, Joseph was somewhat of a musical prodigy. He had one older sister, Clementine (6/1875). Zachariah (listed as Taylor in the 1880 census) had been working as a cook for some time when his son was born. Joseph was surrounded by music at an early age as Cincinnati was full of bands, orchestras and choirs sponsored by all manners of organizations, as well as a noted music conservatory. His original instrument, perhaps picked by his mother, was the violin. In spite of considerable efforts by an early German music teacher, Joe seemed unable to pick up the ability to read music, learning primarily by rote but doing so with great facility. As Clementine did continue with lessons on the piano, Joe was able to pick up some of his skills by listening to and copying her. He also was able to take in some of Cincinnati's music scene, including some pre-ragtime musings of syncopated piano pieces played by local and itinerant musicians.

As Clementine did continue with lessons on the piano, Joe was able to pick up some of his skills by listening to and copying her. He also was able to take in some of Cincinnati's music scene, including some pre-ragtime musings of syncopated piano pieces played by local and itinerant musicians.

As Clementine did continue with lessons on the piano, Joe was able to pick up some of his skills by listening to and copying her. He also was able to take in some of Cincinnati's music scene, including some pre-ragtime musings of syncopated piano pieces played by local and itinerant musicians.

As Clementine did continue with lessons on the piano, Joe was able to pick up some of his skills by listening to and copying her. He also was able to take in some of Cincinnati's music scene, including some pre-ragtime musings of syncopated piano pieces played by local and itinerant musicians.Around the mid-1890s the family moved to Saint Louis, Missouri, where Zachariah managed a billiards parlor. Over the next several years, given that his father's establishment was near the tenderloin district of Saint Louis, Joseph wandered around the town, probably listening to the earliest performances of ragtime performed by Tom Turpin or his contemporary Louis Chauvin in the brothels and the saloons. He picked up some of his early ragtime skills from Turpin, and more importantly, the desire to learn to read music as Tom had. With Turpin's guidance, he learned to read and write music notation sufficiently in order to become not just a player, but a versatile performer and composer.

Encouraged by his progress by 1896, now in his teens, Joe found his way to Jefferson City, the capitol of Missouri, to study music at the Lincoln Institute (current day Lincoln University). The school had been founded specifically for educating former slaves after the Civil War, and remained a black run institution expressly to educate people of color. Joe's additional training at the very least included some theory, harmony, composition, and notation; but shining most in performance on both piano and violin. He also took up percussion, trombone, cornet and upright bass to his repertoire of instruments. It appears that Joe took some time in 1899 to travel with a small band, initially the Georgia Up-to-Date Minstrels, followed by a stint with the A.G. Allen minstrel troupe. It is more than likely the same Joe Jordan that is mentioned in a September 30, 1899 article in The Freeman:

Notes from A.G. Allen's New Orleans Minstrels: "We are still en route South and gathering in all the money. The Palmers, Ruby and Dan, have added new songs to their already hot act, the 'Black Eighth Regiment,' written by Mr. Palmer for his act is a hit nightly. Joe Jordan, leader of our orchestra is recovering from an attack of malaria fever. Moses Terry, our chef, sends regards to James Crosby. Grane, Hopkins, Isler, sends regards to all Cyclones and friends. The ghost still walks every Monday after dinner.

After he had completed his education and travels, Joe returned to Saint Louis. The 1900 census taken on June 5 shows him with his family in that city. Zachariah was running his own restaurant at that time, possibly an extension of the billiard parlor. Joe was listed as a musician with a birth year of 1880. That he does not show up in the 1880 census with the family negates that year as a potential possibility. Interestingly enough they were living next door to Sylvester and Abraham Chauvin, also musicians, and either older brothers or cousins to Louis Chauvin. Surprisingly, Joe was found in the same enumeration taken three days later in Chicago on June 8th where he also listed himself as a musician, this time questionably claiming to be 19. He was either there to perform or for a visit, as his home base was still Saint Louis. His first known published piece, The Century March, was copyrighted from Saint Louis on June 30, 1902, further reinforcing that contention.

He was either there to perform or for a visit, as his home base was still Saint Louis. His first known published piece, The Century March, was copyrighted from Saint Louis on June 30, 1902, further reinforcing that contention.

He was either there to perform or for a visit, as his home base was still Saint Louis. His first known published piece, The Century March, was copyrighted from Saint Louis on June 30, 1902, further reinforcing that contention.

He was either there to perform or for a visit, as his home base was still Saint Louis. His first known published piece, The Century March, was copyrighted from Saint Louis on June 30, 1902, further reinforcing that contention.From 1900 to 1904, Joe spent a lot of time in the Saint Louis area playing the piano and singing. He learned even more about the craft from Turpin, a considerable force of nature, and performed regularly with Turpin, Chauvin and Sam Patterson, and possibly even with Charles Thompson at times. Jordan, Chauvin, Patterson and Turpin formed a piano quartet that played everything from the Saint Louis clubs to church socials, and almost anywhere that two to four pianos could be found in the same space. He also played violin and sometimes percussion with the ten-piece Taborin Band. Jordan was tall at nearly 6' and handsome, so he certainly had little trouble finding places to perform, from the brothels to the popular black entertainment venues. In one of Turpin's Rosebud Café widely attended piano competitions, Jordan, by acclamation, came in second to Chauvin, a daunting achievement given the descriptions of the playing of Louis and his peers.

His skills directly out of his college experience were enough that Joe was able to contribute one or more compositions to the vaudeville sketch show Sons of Ham, which was compiled by Will Marion Cook, Alex C. Roberts, Bert Williams, and other black New York composer/performers. This implies to some degree that he had gone to New York City in 1900, but confirmation was hard to find. Even though the show met with some success in New York, then on a wide tour around the United States, it appears that none of Joe's pieces were published. Still, it helped cement a relationship with the classically trained and somewhat prickly Cook that would manifest itself into much more within a few years. This experience also no doubt whet his appetite to do more writing for the stage.

Once back in Saint Louis, Joe had two of his works, The Century March and Double Fudge, the latter a rag two-step, issued by Joseph F. Hunleth, a largely unknown local publisher. He also did another short tour with the A.G. Allen Minstrel Company. Then with Patterson and Chauvin he wrote an ambitious musical titled Dandy Coon in 1903. With Joe as the music and stage director, they endeavored to open it in Saint Louis, then take it on the road. Featuring a cast of thirty and a "beautiful octoroon chorus," the show folded on the road in Des Moines, Iowa after just a few performances. Only scant remnants of the production remain. While in town, he sold his next rag, Nappy lee, named for a wild-haired musician friend, to publisher J.E. Agnew, who later sold it to the Arnett-Delonais firm in Chicago. The latter distributed the most common edition of the piece. At this point, looking for a better use of his skills, Jordan departed for Chicago, Illinois, in late 1903 or early 1904 to seek out work.

The Rise to the Top - Chicago

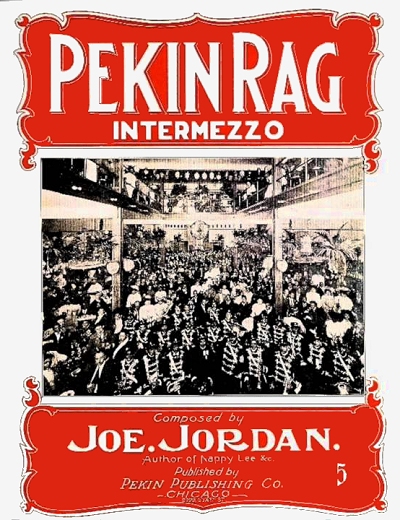

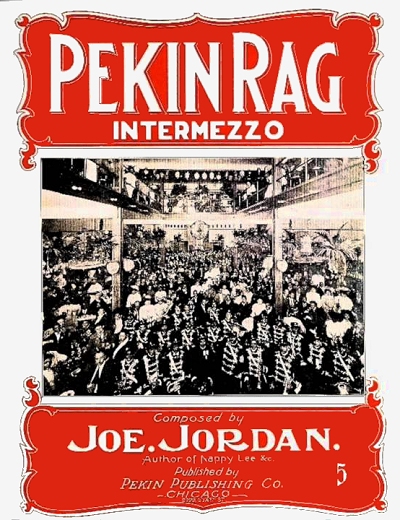

Joe's efforts were validated when he got a job at the Pekin Beer Garden in Chicago at the corner of 27th and State Street. It was owned at that time by gambler and kingpin Robert T. Motts, who had visions of the first successful black-run theater enterprise in the Windy City. Joe played in some capacity at the Pekin as well as other venues around town. In mid-1904 Jordan briefly left that post to return to Saint Louis where he reportedly played at the Louis and Clark Exposition on the pike at the Faust Restaurant. By late in the year Jordan was back in Chicago, where he would be theoretically based for at least the next three decades, and many of his colleagues had migrated there from Saint Louis as well as some of the opportunities for black players had dried up after the fair closed. Joes prowess at orchestral arrangements and music direction quickly found him indispensable to Mott who soon morphed his beer garden into the influential and highly regarded Pekin Theater, one of the earliest African-American owned enterprises of its type in the United States. The Pekin Rag was written for and published by the venue even before its transformation. Joe was soon leading the orchestra at the Pekin and arranging for them as well.

By late in the year Jordan was back in Chicago, where he would be theoretically based for at least the next three decades, and many of his colleagues had migrated there from Saint Louis as well as some of the opportunities for black players had dried up after the fair closed. Joes prowess at orchestral arrangements and music direction quickly found him indispensable to Mott who soon morphed his beer garden into the influential and highly regarded Pekin Theater, one of the earliest African-American owned enterprises of its type in the United States. The Pekin Rag was written for and published by the venue even before its transformation. Joe was soon leading the orchestra at the Pekin and arranging for them as well.

By late in the year Jordan was back in Chicago, where he would be theoretically based for at least the next three decades, and many of his colleagues had migrated there from Saint Louis as well as some of the opportunities for black players had dried up after the fair closed. Joes prowess at orchestral arrangements and music direction quickly found him indispensable to Mott who soon morphed his beer garden into the influential and highly regarded Pekin Theater, one of the earliest African-American owned enterprises of its type in the United States. The Pekin Rag was written for and published by the venue even before its transformation. Joe was soon leading the orchestra at the Pekin and arranging for them as well.

By late in the year Jordan was back in Chicago, where he would be theoretically based for at least the next three decades, and many of his colleagues had migrated there from Saint Louis as well as some of the opportunities for black players had dried up after the fair closed. Joes prowess at orchestral arrangements and music direction quickly found him indispensable to Mott who soon morphed his beer garden into the influential and highly regarded Pekin Theater, one of the earliest African-American owned enterprises of its type in the United States. The Pekin Rag was written for and published by the venue even before its transformation. Joe was soon leading the orchestra at the Pekin and arranging for them as well.While still primarily based in Chicago, Joe appears to have made a couple of trips to New York and collaborated with many of the notable writers there, including Cook who had followed his Clorindy with the first truly successful black musical on early Broadway, In Dahomey. By some accounts, the story is that in mid-1905 Joe was either asked to come to New York by, or happened to be there when he first met "coon song" composer Ernest Hogan, who sometimes billed himself as the "unbleached American." He allegedly contributed to the score of Hogan's newest stage play, Rufus Rastus. It was Hogan's attempt to boost his name further following his success in Will Marion Cook's Clorindy a few years earlier. It is possible that Jordan did some of the transcriptions of the tunes for Hogan, who was not as musically literate. They included Oh Say, Wouldn't It Be A Dream composed to lyrics by Earle C. Jones, and Take Your Time (copyrighted 1907) with Harrison Stewart, interpolated at the very least into the traveling version of the production during rehearsals in late 1905. Rufus Rastus lasted only eight performances on Broadway, yet it remained a success in many other venues for some time, particularly Joe's songs. He also played drums in the pit orchestra for the initial run with Hogan.

Hogan also created a bold collaboration with Will Marion Cook and rising star James Reese Europe, resulting in The Memphis Students, a group comprised of seventeen singers, dancers and musicians, although not actually students and most not from Tennessee. This troupe was successful in both the United States, then on a subsequent European tour in which Jordan did not participate. However, Joe did become involved with them in 1908 when the group was brought back together for a run that lasted several weeks on Broadway, part of it as a tribute to Hogan who was ill, and died the following year. Composer Ford Dabney also was involved with the group, and their renewed success eventually led to great opportunity for black musicians in New York City, encouraging many of them to form the famous Clef Club in 1910.

Back in Chicago, in 1905 Mott decided to create a full-fledged professional theater complete with a resident company to perform original shows, and the addition was completed in 1906 when Jordan had returned from his travels.

Among those engaged for the premier season of the Pekin were Cook, lyricists James Tim Brymn and Will H. Vodery, and Jordan as the resident music director and composer. During his tenure there, Jordan performed and wrote a substantial number of largely unpublished works for the productions staged by the Pekin Theater Stock Company, and gained the attention of black performers and writers around the country. For his initial weekly salary of $25, Joe not only led the pit orchestra, but had an ensemble that played in the adjoining restaurant as well. Some of his pieces did make it into print, including a couple written with Cook and prior works with Hogan. But he was becoming more known for his instrumentals as well, including his Bouclaire Waltzes and the innovative and self-titled J.J.J. Rag.

|

Joe's first big production in 1906 was The Man from 'Bam, which was a full-fledged three act musical comedy written with Vodery. The initial run went over 100 performances, and attracted a great deal of attention both in Chicago and around the Midwest and East as high quality production all around. Adjustments to his shows could be made quickly, and Joe, now fully musically literate, could bang out an orchestration within an hour, usually without the need to have it re-copied. This ability was reflected in his sheet music and compositions, as they acquired a well-rounded sound that could be considered a condensed orchestration. He next collaborated on his next major work with Brymn and lyricists Aubrey Lyles and Flournoy Miller. Their production of The Husband which opened in April of 1906 in Chicago eventually made it to New York City in August of 1907, but in spite of its Midwest success, it ran for only 8 performances on Broadway. A similar fate met Captain Rufus. However, it was perhaps only intended for a short run. Jordan was most likely in New York in 1907 for both of these productions. This led to a multi-month gig for Joe as the musical director for Bob Cole and James Rosamond Johnson's The Shoo-Fly Regiment, which traveled through much of the East and Midwest as well as Canada, according to notices in The Billboard of late 1907. While also trying to contribute to Pekin shows from afar, he was asked by Cook to see what he could come up with for his newest show, Bandana Land starring Bert Williams and George Walker. Joe responded with Somewhere, and it was included in the show when it opened in early 1908, closing more than a year later.

A similar fate met Captain Rufus. However, it was perhaps only intended for a short run. Jordan was most likely in New York in 1907 for both of these productions. This led to a multi-month gig for Joe as the musical director for Bob Cole and James Rosamond Johnson's The Shoo-Fly Regiment, which traveled through much of the East and Midwest as well as Canada, according to notices in The Billboard of late 1907. While also trying to contribute to Pekin shows from afar, he was asked by Cook to see what he could come up with for his newest show, Bandana Land starring Bert Williams and George Walker. Joe responded with Somewhere, and it was included in the show when it opened in early 1908, closing more than a year later.

A similar fate met Captain Rufus. However, it was perhaps only intended for a short run. Jordan was most likely in New York in 1907 for both of these productions. This led to a multi-month gig for Joe as the musical director for Bob Cole and James Rosamond Johnson's The Shoo-Fly Regiment, which traveled through much of the East and Midwest as well as Canada, according to notices in The Billboard of late 1907. While also trying to contribute to Pekin shows from afar, he was asked by Cook to see what he could come up with for his newest show, Bandana Land starring Bert Williams and George Walker. Joe responded with Somewhere, and it was included in the show when it opened in early 1908, closing more than a year later.

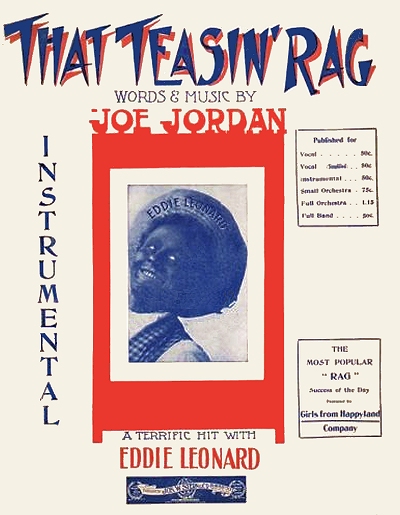

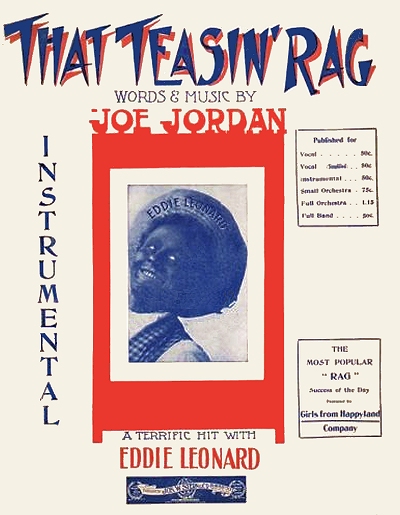

A similar fate met Captain Rufus. However, it was perhaps only intended for a short run. Jordan was most likely in New York in 1907 for both of these productions. This led to a multi-month gig for Joe as the musical director for Bob Cole and James Rosamond Johnson's The Shoo-Fly Regiment, which traveled through much of the East and Midwest as well as Canada, according to notices in The Billboard of late 1907. While also trying to contribute to Pekin shows from afar, he was asked by Cook to see what he could come up with for his newest show, Bandana Land starring Bert Williams and George Walker. Joe responded with Somewhere, and it was included in the show when it opened in early 1908, closing more than a year later.Overall, while pretty much tethered to the Pekin when not on the road, Joe co-wrote no less than fifteen musical comedies between 1906 and 1909, some with Cook and Brymn, and others with Cole, Johnson, and Will H. Dixon. Some of them opened only two to three weeks apart when he was in town, which meant that he spent much of his day writing the next show while keeping the current one in his head and under his fingers to be performed each night, twice on Sunday. This was in part due to the demographic of Chicago being different than New York, where a good show could readily be sustained for months at a time, but with a smaller audience base that was able to afford the Pekin's sometimes lavish admissions, the audiences would be depleted within a month or less, requiring new material to bring them back in. He continued to write instrumentals as well, including his famous That Teasin' Rag which would also be made into a song, featured for some time by George Walker's wife, Aida Overton Walker. Teasin' Rag soon became a hit on the stage, on discs, and even piano rolls, and is still frequently played more than a century later. It was also purloined as part of another piece, as will be discussed. Jordan was truly busy and in demand by this time. However, the strain of trying to work on the road, and the Pekin, and associate with his colleagues in New York became too much, and he resigned from the Pekin in the summer of 1909. This gave him the time he needed to flex his musical muscles and write even more songs. One of them would forever secure his fame as well as its initial performer's launch into a long career.

Taking on Broadway and the World - Domestic and Global Travels

Traveling in a revue for the Pekin in 1910, Joe was on the road and not readily found in the census for that year. However, around that time he left the tour and ended up again in New York City in May, 1910. While there he assisted James Reese Europe with rehearsals for the Clef Club which Europe, Dabney, Vodery, Will Tyers, Jordan and many others had helped to found. Among the pieces featured in the May 27 premiere performance Harlem's Manhattan Casino was Jordan's own That Teasin' Rag, conducted by Jordan and played by 100 newly minted Clef Club members. The show was well-reviewed, and That Teasin' Rag was considered one of the evening's highlights. According to a paper with a largely white readership, the New York Age of June 2, 1910:

It is sometimes said of colored musicians that the only musical sign observed bv them is forte, but to have heard the Clef Club Orchestra Friday evening would have disproved such an assertion. Pianissimo, moderato, crescendo, diminuendo and many other signs were given marked attention by these musicians, who clearly demonstrated that they are capable of playing music as it is written.

Good judgment was shown in the selection of the musical program. The large audience was not inflicted with any of the heavy operas on a warm summers evening, neither were all the numbers ragtime. Evidently it was the intention of the Clef Club to show that it was unnecessary to present heavy numbers to prove that the members know something about music, and that a fitting test of one's musical ability can often be made by properly playing popular pieces. It is to be hoped that they impressed [upon] some singers and musicians present that it is not always what you play, but how you play it. … The colored musicians showed their versatility by also playing ragtime; Joe Jordan's composition, "That Teasing Rag," which was played under the direction of the composer, came in for generous applause.

While Joe was not yet fully established as a New Yorker, his final instrumental rag, the clever and fascinating The Darkey Todalo, was issued there by publisher Harry Von Tilzer. Joe was moving away from the piano rag and toward ragtime songs with a bigger audience, and now was the time for that to happen.

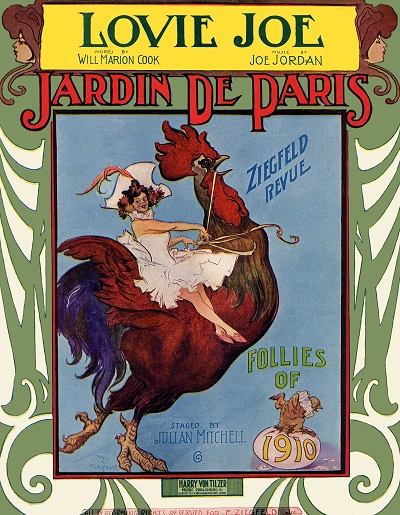

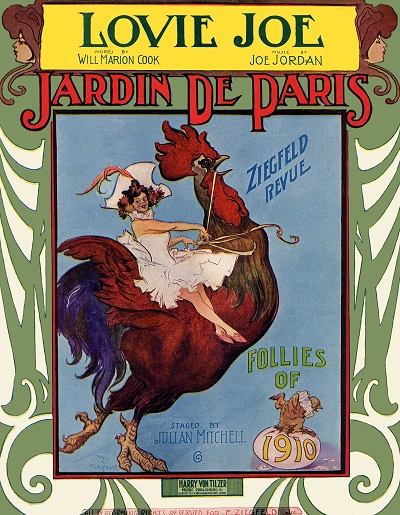

Disregarding the myth perpetuated in the stage play/movie Funny Girl, comedienne Fanny Brice did not audition for the Ziegfeld Follies with Second Hand Rose (some eleven years before it was composed!) and did not debut as a pregnant chorus girl. Accounts of the genesis of her introduction into the 1910 edition of the Follies vary, so there is no accurate version. It is said that when Fanny, 19 at the time, was brought on for the show, she was concerned that she would just be a chorus girl. Taking it up with the boss, Ziegfeld, according to biographer Norman Katkov in The Fabulous Fanny, pointed somewhere in the theater at Jordan and Cook, who evidently just happened to be at the Jardin de Paris that day (a possible coincidence if they were trying to sell a song), and told her she could get a song from them. She reportedly offered the pair a meal at her mother's home if they would come with her to create a piece for her. However they got together, they told her they had no particular piece that would work at that time, even though they would have offered if they had. Then Joe started playing a tune on her upright and she asked if it was available and what it was. Joe said "They call me Lovey Joe where I live, and I call this little old thing Lovey Joe." (Jelly Roll Morton later claimed that the title referred to a great lover. perhaps even implicating himself. Other sources claim he was a real person who owned a New York saloon in the years before the song debuted.) Brice insisted on hearing it, but Joe insisted that it wasn't much and it didn't even have lyrics. With a little persuasion, she worked with Jordan and Cook until Lovie Joe became a song with proper words.

She reportedly offered the pair a meal at her mother's home if they would come with her to create a piece for her. However they got together, they told her they had no particular piece that would work at that time, even though they would have offered if they had. Then Joe started playing a tune on her upright and she asked if it was available and what it was. Joe said "They call me Lovey Joe where I live, and I call this little old thing Lovey Joe." (Jelly Roll Morton later claimed that the title referred to a great lover. perhaps even implicating himself. Other sources claim he was a real person who owned a New York saloon in the years before the song debuted.) Brice insisted on hearing it, but Joe insisted that it wasn't much and it didn't even have lyrics. With a little persuasion, she worked with Jordan and Cook until Lovie Joe became a song with proper words.

She reportedly offered the pair a meal at her mother's home if they would come with her to create a piece for her. However they got together, they told her they had no particular piece that would work at that time, even though they would have offered if they had. Then Joe started playing a tune on her upright and she asked if it was available and what it was. Joe said "They call me Lovey Joe where I live, and I call this little old thing Lovey Joe." (Jelly Roll Morton later claimed that the title referred to a great lover. perhaps even implicating himself. Other sources claim he was a real person who owned a New York saloon in the years before the song debuted.) Brice insisted on hearing it, but Joe insisted that it wasn't much and it didn't even have lyrics. With a little persuasion, she worked with Jordan and Cook until Lovie Joe became a song with proper words.

She reportedly offered the pair a meal at her mother's home if they would come with her to create a piece for her. However they got together, they told her they had no particular piece that would work at that time, even though they would have offered if they had. Then Joe started playing a tune on her upright and she asked if it was available and what it was. Joe said "They call me Lovey Joe where I live, and I call this little old thing Lovey Joe." (Jelly Roll Morton later claimed that the title referred to a great lover. perhaps even implicating himself. Other sources claim he was a real person who owned a New York saloon in the years before the song debuted.) Brice insisted on hearing it, but Joe insisted that it wasn't much and it didn't even have lyrics. With a little persuasion, she worked with Jordan and Cook until Lovie Joe became a song with proper words.Katkov's account continues, perhaps a bit dramatically for effect, the very next morning when Fanny took her song to the stage with Joe at the piano, and the cast erupted into applause at the end of the audition, assuring acceptance of her solo piece into the show. Brice evidently worked very hard on rehearsals of the piece, but at a dress rehearsal a couple of days before opening, Florenz Ziegfeld's producer, Abe Erlanger (who had a stormy history with many performers), thought it to be a trifle, and Brice's blackface interpretation and overall performance as even worse. He took umbrage at the line "I jes' holler, mo'," and came to the stage to tell the former burlesque performer that she would not be using that type of dialect in front of customers who paid good money to see a classy show. She angrily retorted that she knew much more about negro dialects than he did as she lived on 128th Street which bordered Harlem. Both she and the song were quickly dropped from the Follies, but after the rehearsal Ziegfeld insisted they both return over Erlanger's objections. It was launched on the road in Atlantic City on June 6, 1910, with Brice in blackface, but wearing a very tight dress over her large figure instead of the one Ziegfeld had consigned for her. After a performance comprised of uncomfortable wiggling but stupendous singing, she pulled up the skirt, knocked her knees together, then ran off stage with a look of horror. The result was tumultuous applause and eight curtain calls. Once backstage, Erlanger conceded the moment by showing her his straw hat with a hole in it that he had broken while applauding her. Brice kept that hat as a poignant souvenir for the rest of her life. A couple of weeks later on June 20th, Lovie Joe debuted for a New York audience at Jardin de Paris. Jordan was standing outside the theater on the sidewalk as blacks were not allowed in at that time. Just the same, even though he could not share the experience with the audience in spite of the number being from his hand, he could hear to some extent what was going on inside, and was so moved by the audience response he heard that he reportedly wept at the piece's reception. There are reports that Brice had between ten and twenty-seven curtain calls at her Broadway debut. The New York Dramatic Mirror of July 2, two weeks later, noted that it was still getting attention, calling it "…one of the biggest hits of the performance." In spite of its immediate success, there is some possibility that some of this experience prompted Jordan's next major move.

Once backstage, Erlanger conceded the moment by showing her his straw hat with a hole in it that he had broken while applauding her. Brice kept that hat as a poignant souvenir for the rest of her life. A couple of weeks later on June 20th, Lovie Joe debuted for a New York audience at Jardin de Paris. Jordan was standing outside the theater on the sidewalk as blacks were not allowed in at that time. Just the same, even though he could not share the experience with the audience in spite of the number being from his hand, he could hear to some extent what was going on inside, and was so moved by the audience response he heard that he reportedly wept at the piece's reception. There are reports that Brice had between ten and twenty-seven curtain calls at her Broadway debut. The New York Dramatic Mirror of July 2, two weeks later, noted that it was still getting attention, calling it "…one of the biggest hits of the performance." In spite of its immediate success, there is some possibility that some of this experience prompted Jordan's next major move.

Once backstage, Erlanger conceded the moment by showing her his straw hat with a hole in it that he had broken while applauding her. Brice kept that hat as a poignant souvenir for the rest of her life. A couple of weeks later on June 20th, Lovie Joe debuted for a New York audience at Jardin de Paris. Jordan was standing outside the theater on the sidewalk as blacks were not allowed in at that time. Just the same, even though he could not share the experience with the audience in spite of the number being from his hand, he could hear to some extent what was going on inside, and was so moved by the audience response he heard that he reportedly wept at the piece's reception. There are reports that Brice had between ten and twenty-seven curtain calls at her Broadway debut. The New York Dramatic Mirror of July 2, two weeks later, noted that it was still getting attention, calling it "…one of the biggest hits of the performance." In spite of its immediate success, there is some possibility that some of this experience prompted Jordan's next major move.

Once backstage, Erlanger conceded the moment by showing her his straw hat with a hole in it that he had broken while applauding her. Brice kept that hat as a poignant souvenir for the rest of her life. A couple of weeks later on June 20th, Lovie Joe debuted for a New York audience at Jardin de Paris. Jordan was standing outside the theater on the sidewalk as blacks were not allowed in at that time. Just the same, even though he could not share the experience with the audience in spite of the number being from his hand, he could hear to some extent what was going on inside, and was so moved by the audience response he heard that he reportedly wept at the piece's reception. There are reports that Brice had between ten and twenty-seven curtain calls at her Broadway debut. The New York Dramatic Mirror of July 2, two weeks later, noted that it was still getting attention, calling it "…one of the biggest hits of the performance." In spite of its immediate success, there is some possibility that some of this experience prompted Jordan's next major move.In what he later called a way to insulate himself from the sometimes overt and sometimes subtle racism found throughout the United States and often in "show business," Jordan followed the lead of some of his colleagues and decided to take his talents elsewhere for a while where he could live as a part of a better society, accepted for his talent and not judged by his complexion. He teamed with pianist George W. Baker and they set off on a vaudeville tour of the United Kingdom and Europe, billed as "The Emperors of Ragtime." Joe obtained a passport in Hamburg in October 1910, having left on the tour in mid-September. He was listed as a music composer and still a Chicago resident. Curiously the notation "Traveling in Russia" was also on the passport, but if he actually went there on this particular trip is hard to confirm. Jordan and Baker spent many months abroad in Germany, and when they split up he started performing with King and Bailey's musical Chocolate Drops across the continent. After his stint with them, by this time the fall of 1911, Joe toured many of the music halls around the United Kingdom with black singer Maude Turner. They were in Germany by December, when an article appeared in the December 23, 1911, Sunday edition of the Indianapolis Freeman by William Foster using the pseudonym Juli Jones, in an article titled Great Colored Song Writers and Their Songs. Foster singled out and waxed eloquently about Joe and two of his esteemed colleagues, amidst a field of talented black composers:

… The above writers [several were named including Gussie Davis, James Bland and Ernest Hogan] have achieved the distinction of writing songs that have been sung the world over. There are no two writers that have the same method of writing. Only three of the lot could be class as musicians. They are Rosamond Johnson, Will Marion Cook and Joe Jordan. …

Will Marion Cook, whom every one considers erratic, eccentric and very high-tempered, wears the medal as the first educated writer the race can boast of. He can write a whole show that will stand the inspection of the critical musical world. Mr. Book was the master of all the music that Williams and Walker made their great hits with.

Joe Jordon [sic] takes a very peculiar spot as one of America's great colored writers, but stands out when it comes to gems of music. He is contrary to the rule of musical scholars. it is a rule at Leipsic, Germany, that all students must have at least a high school education to take a course in harmony, must be examined for the same or they can't learn harmony. In Jordon's [sic] case he would have had the door shut in his face in disgrace, as he only had a grammar school education. Not knowing or caring for such high education in music or even dreaming that he would ever reach the high perch in the musical world, he started where he could, with a cheap violin. After getting along fairly well with it, he took up piano, cornet, trombone, drums, etc., and stands out to-day as the best all-around player of different instruments of the race, and is considered a master in harmony. …

The critics who have been so harsh on the Negro about his lack of helping supply the world with something besides trouble would do well to look up the music end of literature. They will find that the Negro has cultivated the only thing that the American can boast of being better than the old world has ever been able to produce. There have been thousands of songs written by Negro writers that rightly belong in this article that will never hear of because they have no way of producing their music. The colored song writers of this country have been robbed out of enough melody inside the last 25 years that, if one should put a commercial value on it, would amount to millions of dollars. None of the great colored writers have been able to live off the royalty of their music. [This was a harsh and somewhat inaccurate observation by 1911.]

… The colored song writers of America have proven that when given a chance, they are by far better song writers than their white brothers.

Jordan continued in Germany through late January of 1912 when Joe returned to the United States after nearly eighteen months abroad to see his mother who by that time she had become very ill. Josephine Jordan passed on in mid-February. Zachariah would remarry within a few years.

Finding things changed in Chicago, Joe spent some time in New York during the spring. However, he soon returned, and in June of 1912, with business associate Tom Clark, Jordan opened The Mecca Buffet, a cabaret at 3334 State Street in Chicago. They evidently were looking for high class entertainment as the printed notice of the opening also included an advertisement searching for a "lady violinist and lady celloist" to perform there. By November there were reports of great success for the enterprise in the local newspapers. During the summer the Republican National Convention was held in Chicago, which included the drama of former president Theodore Roosevelt's comeback as a candidate, a man who was very popular with the black population due to his progressive policies and interactions with them. [Composer Scott Joplin composed at least two works involving Roosevelt's character or words.] Joe wrote an inspiring piece specifically for the event title He's Coming Back! Even though Roosevelt lost the nomination, he nonetheless forged forward with a different party, only to lose to Woodrow Wilson in November, quickly negating the market for Jordan's piece.

They evidently were looking for high class entertainment as the printed notice of the opening also included an advertisement searching for a "lady violinist and lady celloist" to perform there. By November there were reports of great success for the enterprise in the local newspapers. During the summer the Republican National Convention was held in Chicago, which included the drama of former president Theodore Roosevelt's comeback as a candidate, a man who was very popular with the black population due to his progressive policies and interactions with them. [Composer Scott Joplin composed at least two works involving Roosevelt's character or words.] Joe wrote an inspiring piece specifically for the event title He's Coming Back! Even though Roosevelt lost the nomination, he nonetheless forged forward with a different party, only to lose to Woodrow Wilson in November, quickly negating the market for Jordan's piece.

They evidently were looking for high class entertainment as the printed notice of the opening also included an advertisement searching for a "lady violinist and lady celloist" to perform there. By November there were reports of great success for the enterprise in the local newspapers. During the summer the Republican National Convention was held in Chicago, which included the drama of former president Theodore Roosevelt's comeback as a candidate, a man who was very popular with the black population due to his progressive policies and interactions with them. [Composer Scott Joplin composed at least two works involving Roosevelt's character or words.] Joe wrote an inspiring piece specifically for the event title He's Coming Back! Even though Roosevelt lost the nomination, he nonetheless forged forward with a different party, only to lose to Woodrow Wilson in November, quickly negating the market for Jordan's piece.

They evidently were looking for high class entertainment as the printed notice of the opening also included an advertisement searching for a "lady violinist and lady celloist" to perform there. By November there were reports of great success for the enterprise in the local newspapers. During the summer the Republican National Convention was held in Chicago, which included the drama of former president Theodore Roosevelt's comeback as a candidate, a man who was very popular with the black population due to his progressive policies and interactions with them. [Composer Scott Joplin composed at least two works involving Roosevelt's character or words.] Joe wrote an inspiring piece specifically for the event title He's Coming Back! Even though Roosevelt lost the nomination, he nonetheless forged forward with a different party, only to lose to Woodrow Wilson in November, quickly negating the market for Jordan's piece.It was reported that at some point in 1913 during a New York visit that Jordan played with both Charley Thompson and Eubie Blake for the first time, but not for the last. After a lull of known activity (although perhaps busy either writing or performing somewhere, in the Spring of 1913 Joe went back to writing for the stage, writing the comic sketch The Composer and the Moving Van with Alvin Joyner. It opened with the pair at the Grand Theater in Chicago in May, and went on the road soon after. Later in the year he brought it to the Pekin Theater, which had been in some decline since the death of owner Motts back in 1911. After a disagreement with the new owner, George Holt, Jordan and Joyner migrated to the States Theater in Chicago, which was a multi-purpose cinema and vaudeville house. He took the Pekin orchestra with him, and they spent some time playing for the films that came through as well as for vaudeville sketches. Business was good throughout the fall. However, in December 1913 Joe announced his retirement from the States Theater. As he was preparing to do more composing for the stage this was likely a choice to realign his personal capacity. In January the Pekin, which had recently converted to a movie house, lured Joe and his ensemble back to play for them for a considerable sum. However, by February the venue had fallen out of favor with the citizens of South Chicago, and it shut down as well, putting Joe and his orchestra temporarily out on the street. Through other incarnations over the next several years, the once grand Pekin Theater died an agonizing death through mismanagement and deterioration.

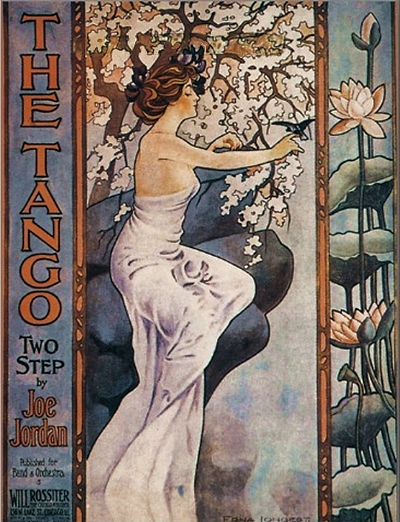

Possibly frustrated with Chicago once again, Joe went back to New York and renewed his involvement with James Reese Europe and Will Tyers, playing with their newly formed Tempo Club, a high-brow subset of the Clef Club. With that organization he helped conduct some of the music on April 8, 1914, at the National Negro Orchestra's concert of African American Music, which was held at the Manhattan Casino once again, hosting a large audience. Among the pieces debuted there was his dance two-step The Tango, capitalizing on the latest of many dance crazes that had swept the country after the emergence of Vernon and Irene Castle, with whom Europe and Dabney had been involved with for some time as musical contributors. The Castles were also a featured part of the evening. According to the New York Age review published April 16, 1914:

|

The debut of the National Negro Orchestra was most successful. Particular attention was paid to the instrumentation introduced by James Reese Europe, The large number of banjos and guitars being as conspicuous by their absence as were the violins and brass instruments by their presence.

The audience at the Tempo Club entertainment was large and brilliant. The boxes were occupied by representative members of both races, and Easter costumes were much in evidence. James Reese Europe and his associates … are to be congratulated upon furnishing amusement lovers with such a unique program.

Joe spent much of the remainder of the year on the road, emerging now and then in the New York show business trade papers. He staged one act in early 1915 known as The Seven Tangaroons, doing a brief vaudeville tour. In the spring of 1915 Jordan was engaged for what was initially a two month stint at the London Hippodrome for the revue Push and Go.

He apparently had his own plans that extended beyond that, since his passport application, approved on April 1, 1915, states that he would be going to England and France, and perhaps even Russia. Newspaper accounts indicate that his stint with the Hippodrome lasted only a few weeks, as the show was poorly reviewed, perhaps just misunderstood. It was also a difficult period with war clouds over neighboring Europe, a conflict that would soon encompass the UK. The ensemble Joe had brought along toured England during May into June, when most of them left to return home. Jordan stayed behind with a small core group, and played around London through the summer. The June 12, 1915, New York Clipper noted that Joe's syncopated band, "including Black Lightning, the champion trap drummer," embarked upon a tour of the Empire vaudeville circuit in England. It is unclear where Joe went from there after the tour was complete, but newspaper accounts and various ship records indicate that his time in England lasted into May of 1916, when it became necessary to return due to increasingly treacherous wartime conditions. However, he did not do so without first having acquired something extra from the UK, a new automobile and a wife.

|

She was Miss Nellie Massey, reportedly a white British citizen. When Joe and Nellie were married is unclear, but different reports claim anything from the fall of 1915 into the early spring of 1916. The media, including the New York Age and the Indianapolis Freeman in early June, 1916, editions, claimed he was married in Scotland, and that her father was a well off merchant. He was most likely from England, even though some sources have claimed that she was French and at least one Illinois government source claims she was born in Chicago, probably in error. She was also referred to as an "East Indian maiden" in the Chicago Daily News of December 14, 1916, and one extant photograph of her suggests this as a mild possibility. A description of her in the Freeman as "fair to look upon" does not go that direction, but evidently her father was of East Indian descent. Joe supposedly, according to some later articles, received a dowry himself, a rather amazing occurrence for that period given the miscegenation aspect of the union, but also a show of respect for his talent and stature as a composer and performer. As for the fancy automobile they brought back (the make was difficult to pin down), they drove it on less than reliable roads from New York to Chicago where Joe established a new residence. While he had been showing 3800 Wabash Avenue as his Chicago addresses, this was actually a rooming house where his father, now managing a billiards parlor and saloon, had been staying. Joe and Nellie settled at 3406 South Park Avenue.

Down to Business, then Back to Pleasure - Chicago

Once he was back from Europe and settled in Chicago with his new wife, Joe parlayed his financial gain - some reports claim that he may have been approaching millionaire status but it was likely less than half of that - into an interesting new enterprise - Real Estate. This was not an uncommon pursuit for some of the more prolific songwriters in the business, as many of them owned rental properties or routinely traded up properties they had improved. However, Joe had much more revolutionary plans in mind. He bought a lot at State and 36th Street outside the loop and south of downtown Chicago (near present day Stateway Park). In the fall of 1916 Joe set about erecting the three-story J. Jordan Building, an office building constructed with an investment of $220,000. It was in a predominantly black area of the city, but one that had some level of affluence just the same, and in which most of the structures were white-owned and built. The main entrance was topped by a name plaque with an elaborate lyre as an homage to the music which allowed him this indulgence. Black citizens were inspired by the effort, and many started in on enterprises of their own boosted by Jordan's success. Primarily an office building with retail space on the ground floor, Jordan never lived or worked there, and he didn't even own it for very long. The investment was sound, as the building was quickly occupied upon its opening in 1917.

Once he was back from Europe and settled in Chicago with his new wife, Joe parlayed his financial gain - some reports claim that he may have been approaching millionaire status but it was likely less than half of that - into an interesting new enterprise - Real Estate. This was not an uncommon pursuit for some of the more prolific songwriters in the business, as many of them owned rental properties or routinely traded up properties they had improved. However, Joe had much more revolutionary plans in mind. He bought a lot at State and 36th Street outside the loop and south of downtown Chicago (near present day Stateway Park). In the fall of 1916 Joe set about erecting the three-story J. Jordan Building, an office building constructed with an investment of $220,000. It was in a predominantly black area of the city, but one that had some level of affluence just the same, and in which most of the structures were white-owned and built. The main entrance was topped by a name plaque with an elaborate lyre as an homage to the music which allowed him this indulgence. Black citizens were inspired by the effort, and many started in on enterprises of their own boosted by Jordan's success. Primarily an office building with retail space on the ground floor, Jordan never lived or worked there, and he didn't even own it for very long. The investment was sound, as the building was quickly occupied upon its opening in 1917.Having not done any composing in 1916, or at least nothing that was published or copyrighted, Jordan's extremely light musical output of 1917, pretty much only one patriotic wartime tune, reinforces that his focus had been turned away from his musical pursuits to some degree. Unfortunately, around the same time, it seems that Nellie somehow got Joe involved in an alleged international smuggling scandal. An article in the Chicago Tribune of March 31, 1917, sheds some additional light on the nature his first marriage and his business dealings at that time:

Federal Agents Seize Jewels of Song Writer

Diamonds, valued at $20,000 and brought to the United States a year ago by the white wife of "Joe" Jordan, Negro song writer, were taken from a safety deposit vault in the Lincoln State Bank last Wednesday by federal agents. The government is investigating on the theory that the jewels were smuggled. Jordan lives at 3406 South Park Avenue.

Jordan, whom "black belt" authorities say is worth $250,000, said last night that the jewels were declared to customs inspectors in New York and that his wife was allowed to bring them in without duty as a British subject.

"I married Mrs. Jordan, whom I met in London in theatrical work, eighteen months ago [October 1915]," said Jordan. "We came to New York and the jewels were declared. Recently I had a chance to make a good real estate deal, and my wife consented to allow me to sell a $10,000 necklace. I took it to a loop jewelry firm and they notified the customs agents. They thought they had discovered an international smuggling plot and hurried to my safety vault. The cashier of the bank, John Hardle, called me up, and I came over and unlocked the vault. They took me to the federal building, questioned me, and let me go."

Mrs. Jordan's father, an East Indian merchant, now in New York, is a millionaire, according to those well acquainted with the Jordans. It is also said that Joe Jordan, the merchant's son-in-law, received $50,000 when he married the merchant's daughter. Jordan is now building a three story office building at Thirty-fifth [sic] and State streets.

...His father is the proprietor of a poolroom at 3232 South State street.

Note that in a follow-up article in late May that it was reported that all of the jewels were returned to Nellie without any apologies for the action. A couple of months after the initial incident, Nellie gave Joe a child, Joseph George, born on May 24, 1917. In spite of a different middle name, he was referred to as Joe, Jr.

Jordan's 1918 draft card shows him not as a musician, but in the business of Real Estate and Safe Deposit. In an August 1, 1954, article in the Chicago Daily Tribune concerning the demolition of many south side buildings in the area of State and 35th, Abram Wilson who was known as Red Dick recalled the area at its peak, and Jordan's business in particular:

Not one place ever was closed. "Nobody had a key in those days," says Red Dick. But Negroes did discover that locks had to be placed on their valuables. And Joe Jordan, a well-known band leader married to a Parisian [sic] woman, erected an office building and made a tidy profit renting safe deposit boxes.

It was hard to keep Joe grounded in the business world for very long. In May of 1918 he suddenly sold his building to Louis B. Schmidt. It is unclear if he was having financial issues or just wanted to relieve the burden of being a landlord.

(The J. Jordan building would finally be torn down in 1986 in spite of valiant efforts to preserve it.) The sale may also have been a desire to return to the music world. Jordan was lured back to New York by Cook to be not only the director of the New York Syncopated Orchestra but its financial manager as well. Spending time in both Chicago and New York for the next few years (1919 and 1920 passport records show him still as a Chicago resident using his father's address), he was allowed more opportunities not just for stage performance, but to work on records as well. It also put him near center stage at the beginning of the jazz era. In fact, he was actually heard ON the stage, just not as he had planned.

|

In 1917 the Original Dixieland Jass Band (later Jazz Band) fronted by trumpeter Nick LaRocca, clarinetist Larry Shields and pianist Henry Ragas started recording in New York. One of their first big hits was the Original Dixieland Jazz Band One Step which went by variously modified titles. "Original" was not entirely true, as the trio of the piece was also the verbatim trio of Jordan's That Teasin' Rag. Jordan heard this in 1918 and brought suit against LaRocca and the band, quickly winning a judgment that resulted in the records being recalled and subsequently labeled The Original Dixieland One Step: Introducing "That Teasin' Rag". The introducing part is obviously far from true, but "introducing" became a popular term for pseudo-medleys, particularly with the various orchestras of saxophonist Paul Biese, and it was used as somewhat of gag in 1937 when Benny Goodman recorded Louis Prima's Sing, Sing, Sing (With a Swing): Introducing "Christopher Columbus". In any case, Jordan also received some financial compensation as well as composer credit, a deal which benefited him for many years.

Now in charge of Cook's orchestra, which was formed mostly to play Cook's music, the writing muse hit once again, and Jordan offered up the ballad Happiness. But that was evidently not in the cards for his personal life. Jordan had been managing and conducting shows throughout 1919 and 1920 after the was had ended, and went on the road with them as well. It was understandably difficult to take his wife and toddler along with him in most cases, which may have caused some marital stress. In April of 1919 he renewed his passport to work in Britain, and it is unclear if they went along with him for his few months over there. The passport was renewed once again in January of 1920, noting he was now going to France for employment as a musician. It is possible he was out of the country for the 1920 enumeration, or at least in transit. Perhaps in an attempt to mend things, the passport renewed again in mid-June, adding on Nellie and Joe, Jr. It also clarified his purpose, as Joe wrote this note for the amended document:

I am [a] musician and have authority to work in Paris, and as my line of work is very dull here at present and I have a job existing for me with Lee A. Mitchell and can desert to go to Paris.

It is unclear who Lee Mitchell was. However, there is a probability that Joe ended up not going abroad that June, or that the trip was truncated. Joe and Nellie's son, Joe Jr., took ill, and died in Chicago on July 31, 1920. This evidently put additional strain on the marriage, and at some point prior to 1921 the couple was divorced, but the terms of any settlement were kept out of the press. This was the last that was heard from Nellie, who was difficult to trace beyond that time. It was in this same period, and perhaps even before, that Joe met his future and final wife, Illinois native Irene Berenice Hudlin. Joe and Irene were married in Manhattan on June 4, 1921, just a month after his father Zachariah had died in Chicago at age 73. The Jordan's son Lowell Henry was born the following year in Chicago on May 25th, and their daughter Marie would follow on July 25, 1923, both born in Chicago.

Staying Relevant in the Jazz Era - New York

From 1921 to 1922 Joe was engaged to direct some shows, and perhaps just pull them together with his musical expertise, an effort which did not always yield the best of results. One of them, Ebony Nights, by Henry Creamer and J. Turner Layton, had not done well on the road, closing before it got to Broadway. Their next show in 1922, Strut Miss Lizzie, fared much better in terms of reviews with Joe at the helm, also having contributed a couple of tunes, but it still failed to draw audiences and the requisite necessary revenue. Given the success of Eubie Blake and Noble Sissle's Shuffle Along in 1921, there was clearly a market for a black written and produced musical, so Joe kept trying to find the right property.

Late in 1922 he succeeded with Streets of Cairo which opened in Chicago on November 11. It was followed by the revue Ginger and Spice in late December, also in Chicago. Somewhere along the way he also copyrighted the song Brother in Law Dan, which was a late sequel to Lovie Joe. However, it was not picked up by Brice like its predecessor had been, although it enjoyed some success on record. His experience with orchestrating the shows he had worked on got him a position with Melrose Music in Chicago to create some stock orchestrations for their stage catalog, intended for bands and orchestras.

|

Jordan went on tour from 1923 into perhaps 1925, going to various motion picture theaters in the Loews chain, often performing with violinist Willie Tyler for special shows. When he eventually decided to stay in New York City the company gave him a steady position in their prestigious theater there. An article in the Music Trade Review of June 23, 1923, highlights Joe's role that year as the musical director of the enormous (3,300 seats) Loew's State Theater located in Manhattan at 1540 Broadway in Times Square:

Joe Jordan… has been featuring several numbers from the Bee Tee Publishing Co.'s catalog the past week, including the "Grand-daddy" number, which is incorporated in an overture composed of all the old "Daddy" songs. "Grand-daddy" comes in for special featuring, inasmuch as it is also sung by Lillian Leonard, with a special setting quite unique for a vaudeville house.

Still oscillating between his two adopted cities, Joe had a cadre of players in each location who he used as his stock band for special events, private parties, and some stage work. Among the most notable of them was Joe Jordan's Sharps and Flats, made up mostly of his Chicago colleagues. By the summer of 1925 Joe was engaged by the Columbia Theatrical Circuit. His latest show, Rarin' to Go, toured from August of 1925 well into late 1926, keeping Joe and his gang well occupied during that period, in spite of neutral reviews. Of some interest is that there were both white and black casts with this revue, but they usually performed the show segregated, with the white cast taking on the first half, and the black cast the second. While his band was in New York, Jordan finally got into a recording studio, as he cut four sides with his group in May and July 1926 as The Ten Sharps and Flats. Two were on the prestigious Columbia Records label, among the earliest electronic recordings by a black group, and two others were released under the lesser known Banner Records imprint. Joe is supposed to have released additional sides under other names as well. Black composer and publisher Clarence Williams was involved with these sessions in some way, and he ended up hiring Joe as a staff composer for a couple of years. Williams added lyrics to Joe's eclectic piece Tampico, which was recast as Morocco Blues, one of the pieces the ensemble recorded at both of the 1926 sessions. With Williams he wrote the revue Bottomland which opened in New York in June of 1927.

Joe is supposed to have released additional sides under other names as well. Black composer and publisher Clarence Williams was involved with these sessions in some way, and he ended up hiring Joe as a staff composer for a couple of years. Williams added lyrics to Joe's eclectic piece Tampico, which was recast as Morocco Blues, one of the pieces the ensemble recorded at both of the 1926 sessions. With Williams he wrote the revue Bottomland which opened in New York in June of 1927.

Joe is supposed to have released additional sides under other names as well. Black composer and publisher Clarence Williams was involved with these sessions in some way, and he ended up hiring Joe as a staff composer for a couple of years. Williams added lyrics to Joe's eclectic piece Tampico, which was recast as Morocco Blues, one of the pieces the ensemble recorded at both of the 1926 sessions. With Williams he wrote the revue Bottomland which opened in New York in June of 1927.

Joe is supposed to have released additional sides under other names as well. Black composer and publisher Clarence Williams was involved with these sessions in some way, and he ended up hiring Joe as a staff composer for a couple of years. Williams added lyrics to Joe's eclectic piece Tampico, which was recast as Morocco Blues, one of the pieces the ensemble recorded at both of the 1926 sessions. With Williams he wrote the revue Bottomland which opened in New York in June of 1927.In early 1928 pioneering stride pianist and composer James P. Johnson composed his answer to Sissle and Blake's show Shuffle Along, calling it Keep Shufflin'. It was produced by the famous white Jewish gangster Arnold Rothstein. Johnson hired Jordan as conductor and perhaps arranger, leading a group that included Johnson, his protégé and co-composer Fats Waller, Jabbo Smith and other prominent jazz musicians. After a successful season in New York, the show toured major cities through most of the year. It might have gone longer if not for the murder of Rothstein over gambling debts on November 4, 1928. After his successful run with the show, Jordan took some of the band on tour as a new formation of the Sharps and Flats.

Back in New York just ahead of the start of the Great Depression, steady stage work was getting harder to find. However, Joe still had kept some of his investments outside the stock market so he would not lose it all when the financial structure finally collapsed. Some of that capital was invested into a new show called Deep Harlem which opened on the road in October, 1928, at the Lafayette Theatre off Broadway. With a book by Salem Whitney and J. Homer Tutt, and lyrics by Tutt and veteran Henry Creamer, there was a lot of hope for this all black production, with a libretto that chronicled the history of blacks from Africa to modern day New York. It was described in an early review in the October 6, 1928 edition of the New York Age:

By far the most impressive and imposing scenes which have ever been staged in a local theatre are part of "Deep Harlem." Among these scenes are the ancient forest home of the Kushite tribe and arid desert encampment to which this tribe is driven by heartless slave drivers, a convict ship, a southern plantation, a convict farm, a popular Harlem gin mill—and the Lafayette Theatre. An unusually large cast is presenting "Deep Harlem. There are seventy-five entertainers in all…

The elaborate production finally opened on Broadway on January 7, 1929, at the Biltmore Theater. However. it received poor reviews in the mainstream press and was pulled after only eight performances.

During the rest of the year and into the early 1930s Jordan and his band were heard over the airwaves in New York from time to time, plus many appearances with him as an accompanist to an instrumentalist or singer.

|

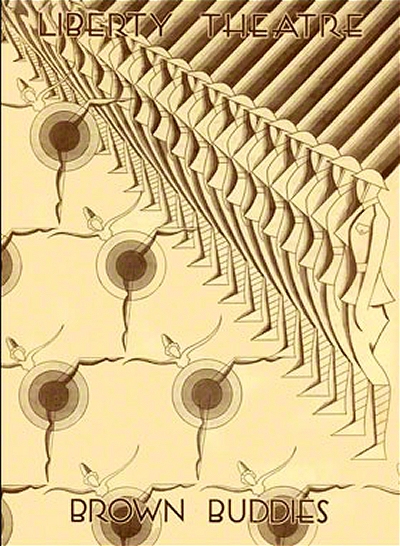

In the 1930 census the Jordan family was found living in Manhattan on West 112th Street, with Joe listed as a band musician. They also had one boarder living with them, a Manhattan elevator operator. Evidently eager to still have a go at Broadway he engaged in a new show, Brown Buddies, a "Musical Comedy in Sepia." The core of the music was composed with Millard Thomas, but it also featured tunes by his colleagues Shelton Brooks, Ned Reed, Porter Grainger, J.C. Johnson, J. Rosamund Johnson, George A. Little, Arthur Sizemore and Edward G. Nelson. The story followed a group of black soldiers from East Saint Louis, Illinois, during World War I. Opening at the Liberty Theatre in October it ran a fairly solid 111 performances into January 1931. The show didn't hurt for star power either, with dancer Bill "Bojangles" Robinson and singers Ada Brown and Adelaide Hall commanding the stage.

In the summer of 1931 Joe was asked to help orchestrate some of the numbers for the somewhat depleted Ziegfeld Follies of that year. Things were tough for musicians and the American people in general over the next couple of years, but with the election of Franklin Delano Roosevelt in late 1932, opportunities for enterprising Americans were clearly around the corner, and Joe was most certainly one of them. Interested in the welfare of his fellow musicians, and hoping to advocate for them as well, he was elected to the leadership of the American Federation of Musicians Local 802, of which he had been a member for some time as soon as the organization allowed black musicians into its membership. From his position on the Trial Board of that body, and during a difficult time for everybody in the United States, not just blacks, he was able to provide a voice that helped them achieve some level of equity, even though racial discrimination was still widely practiced throughout the country.

Starting in 1933 Jordan led the WPA-sponsored Federal Theater Project's Negro Unit Orchestra throughout the 1930s. He composed music for the annual Lew Leslie's Blackbirds revues for 1933 and 1934,

both of which starred Bill Robinson. Joe was also engaged by the Shubert brothers to help fix or update scores for revivals in their theater chain. In 1935 he assisted with orchestrations for the Broadway revue Smile at Me which lasted nearly a month at the Fulton Theatre. For one production in 1936 which included James P. Johnson, Asadata Dafora and Porter Grainger, the 110-piece Negro Unit Orchestra, funded by the WPA and led by Jordan, provided underscore music for a production of William Shakespeare's Macbeth as staged by a young Orson Welles. It had been reconceived as a 19th century story set in Haiti, causing some to call it the "Voodoo Macbeth," and opened at Harlem's Lafayette Theatre in April 1936 for a short by successful run. The following year Joe was again engaged on Broadway, this time as the sole arranger for the musical comedy Sea Legs, which died after a mere two weeks at the Mansfield Theater. When he wasn't in the pit or working on a new score, Jordan held forth at the piano of the Poosepahtuck Club in central Harlem. There were some later suggestions that his piano bar playing was the inspiration or prototype for the character of the pianist Sam played by Dooley Wilson in the 1942 film Casablanca, but it is difficult to pin that down as fact.

|

A great triumph came in 1939 when Jordan at last performed in Carnegie Hall, leading a 75-piece symphony orchestra and 350 voice choir for the ASCAP Silver Jubilee Festival. He had finally joined ASCAP just in advance of the event. The group opened the week of celebration with Lift Every Voice and Sing by Rosamond Johnson and H. Weldon Johnson. The event was successful enough that the entire program was taken out to the San Francisco Golden Gate Exposition, then to the opening of the famous 1939 edition of the New York World's Fair. In November 1939 it was announced that Joe had been hired by the Handy Brothers' Music Company to work in the arranging department, and as a liaison with broadcasting and recording concerns. In the 1940 census, taken in Manhattan, Joe, Irene, Lowell, Marie and Irene's mother were all living together, Joe listed simply as "musician."

and as a liaison with broadcasting and recording concerns. In the 1940 census, taken in Manhattan, Joe, Irene, Lowell, Marie and Irene's mother were all living together, Joe listed simply as "musician."

and as a liaison with broadcasting and recording concerns. In the 1940 census, taken in Manhattan, Joe, Irene, Lowell, Marie and Irene's mother were all living together, Joe listed simply as "musician."

and as a liaison with broadcasting and recording concerns. In the 1940 census, taken in Manhattan, Joe, Irene, Lowell, Marie and Irene's mother were all living together, Joe listed simply as "musician."Joe started out the 1940s writing the score to De Gospel Train to libretto and lyrics by J. Homer Tutt and Henry Creamer. The story, which was a satire farce about a group of Negros riding in a segregated railroad coach, did not resonate with its producers, so it never saw the light of day. Still working with Handy, Jordan helped him compile a folio of tributes to famous African-Americans throughout history, contributing some choral works to the project. (It was issued by Handy as Unsung Americans Sung in 1944.) Also in 1941, Joe reformed his band and led them in a traveling revue called Here 'Tis, which was written by Jesse James, Eddie Hunter and James C. Johnson.

Jordan once again found relevance and fulfilling work with many black Army bands and USO groups during World War II. He also did some benefits for the Red Cross. His 1942 draft record shows him living at 188 W. 135th Street in Harlem, and employed by the Rubsam and Horrmann Brewery Company in Stapleton, Staten Island. Whether this was just a stop-gap job or if he was working as an investor or in a similar capacity is not clear. After he went through officer training, part of the war was spent by Captain Joe Jordan posted at Fort Huachuca in Arizona to oversee the morale boosting needs of the Army's black soldiers. While there he organized bands and orchestra, wrote and arranged shows, staged dances, and formed a vocal group called the Deep River Boys. At one point racial tensions were running high on the base, and Jordan diffused them by distraction, starting a new show that involved everybody and kept them quite busy. He was forced to retire from his post in 1944 due to a proclamation from President Franklin Delano Roosevelt requiring personnel to step down at age 60, and he was 62 at the time. Still, he stayed on for a bit longer in Arizona as a civilian advisor and U.S.O. performer, and some copyrights and copyright renewals appear from that location from 1944 in the Library of Congress records, including one written for Fort Huachuca.

A Change of Pace and Rediscovery - Tacoma

After the war was over Joe was still musically viable, but in the changing musical world of New York City, less relevant in many respects. In the waning months of the war he had been transferred from Arizona to to Fort Lewis in Tacoma, Washington, conducting groups there in his new role as a civilian,

and was instantly attracted to the area which was very much different than the urban existence he had been a part of for decades in Chicago and New York. The views of Mount Rainier were evidently much more inspiring that the Manhattan skyscrapers or Harlem nightclubs. So it was that after the armistice, Jordan moved his family and his life from New York to Tacoma where he would spend the rest of his life. Over the next several years he gave piano lessons and eased his way into local politics as a member of the Republican party. He also served for a time in the local sheriff's department. The 1950 census taken in Tacoma showed him as a real estate sales manager, and Irene as a social worker for the Pierce County Welfare Office. There was no official indication of his musical activity. In the mid-1950s Joe surfaced as a lounge attendant for the state senate in the capital city of nearby Olympia. A picture of him playing during a break was accompanied by a statement that, "Once bitter about the 'color barrier,' Joe now feels prejudice is waning because of 'something changing in people's hearts.'" This was right on the cusp of the Civil Rights movement in the Southeast United States, so he was definitely in touch with the pending change.

|

Joe had became involved with real estate once again in the late 1940s, and with great success, but he also continued to compose and publish songs. Among his final compositions was one crafted, perhaps commissioned, for the 100th anniversary of the founding of Tacoma. He also wrote a state song, one for a local minor league baseball team, and some songs for various schools in the Tacoma public school system. One of those was for Lincoln High School, and the proceeds from the sales of that song went not to Joe, but instead toward the purchase of a new Steinway piano for the school. Historian and ragtime pianist Johnny Maddox also befriended Jordan during this period, and eventually came into a large number of his musical scores and private acetate recordings. The number of pieces he wrote varies, depending on source, from over 600 to perhaps 2000, most of them unpublished yet many of them still copyrighted with the Library of Congress. On a sad note, Joe's wife Irene passed on in the March of 1961 at age 62 and just short of 40 years of marriage.

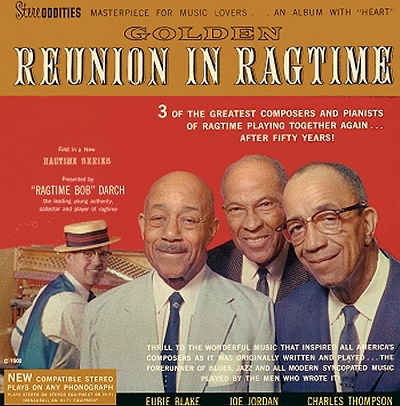

Another emerging ragtime figure to seek out Jordan was Robert Darch, who after working diligently to mine Jordan for information on his life story made a bold effort to secure his place in ragtime history via a recording. In 1962, Darch arranged a Fort Lauderdale, Florida, recording session for Joe along with his two long-ago friends from New York and Saint Louis, Charley Thompson and Eubie Blake. The resulting session, one of the first of its kind in glorious stereo, was issued as a special broadcast set and edited down to the Golden Reunion in Ragtime record on the Stereoddities label. It was reportedly one of the most joyous occasions of his later life, as well as Thompson's, and some of his great history is revealed through anecdotes along with both solo and group performances. Among the standout pieces from the session was the trio's rendition of his piece Old Black Crow, and Until, a beautiful sung tribute to his late wife Irene. But some of that racial injustice that Joe had long been fighting emerged once again when it was found that hotels in Fort Lauderdale would not host the three black performers, forcing them to be driven up to the studio from Miami by Darch.

In 1962, Darch arranged a Fort Lauderdale, Florida, recording session for Joe along with his two long-ago friends from New York and Saint Louis, Charley Thompson and Eubie Blake. The resulting session, one of the first of its kind in glorious stereo, was issued as a special broadcast set and edited down to the Golden Reunion in Ragtime record on the Stereoddities label. It was reportedly one of the most joyous occasions of his later life, as well as Thompson's, and some of his great history is revealed through anecdotes along with both solo and group performances. Among the standout pieces from the session was the trio's rendition of his piece Old Black Crow, and Until, a beautiful sung tribute to his late wife Irene. But some of that racial injustice that Joe had long been fighting emerged once again when it was found that hotels in Fort Lauderdale would not host the three black performers, forcing them to be driven up to the studio from Miami by Darch.

In 1962, Darch arranged a Fort Lauderdale, Florida, recording session for Joe along with his two long-ago friends from New York and Saint Louis, Charley Thompson and Eubie Blake. The resulting session, one of the first of its kind in glorious stereo, was issued as a special broadcast set and edited down to the Golden Reunion in Ragtime record on the Stereoddities label. It was reportedly one of the most joyous occasions of his later life, as well as Thompson's, and some of his great history is revealed through anecdotes along with both solo and group performances. Among the standout pieces from the session was the trio's rendition of his piece Old Black Crow, and Until, a beautiful sung tribute to his late wife Irene. But some of that racial injustice that Joe had long been fighting emerged once again when it was found that hotels in Fort Lauderdale would not host the three black performers, forcing them to be driven up to the studio from Miami by Darch.