Joseph Francis Lamb (December 6, 1887 to September 3, 1960) | |

Ragtime Compositions Ragtime Compositions | |

|

1903

Walper House Rag1905

Ragged Rapids Ragc.1907

Hyacinth - A RagGreased Lightning (c.1907/1959) Rapid Transit (c.1907/1959) 1908

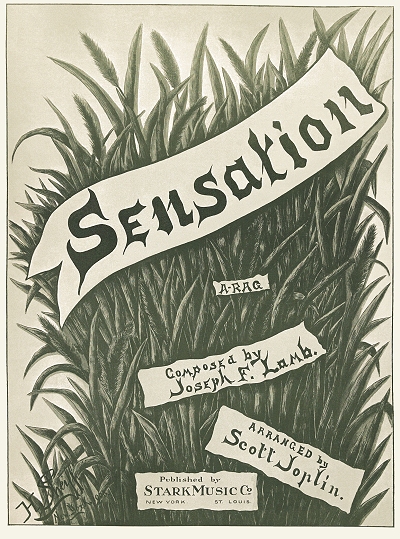

Rag-Time Special (c.1908/1959)Joe Lamb's Old Rag (c.1908/1959) Sensation Rag Dynamite Rag 1909

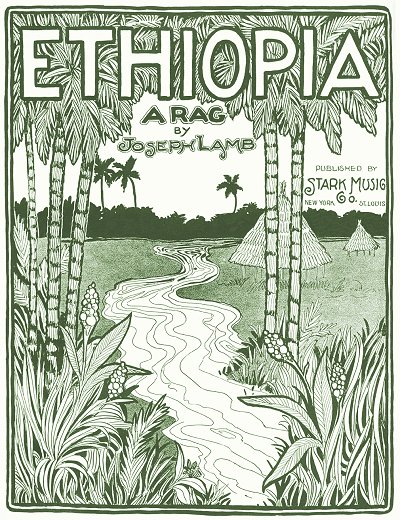

Ethiopia RagExcelsior Rag 1910

Champagne Rag1912

Spanish Fly1913

American Beauty Rag1914

Chasin' The Chippies1915

Contentment RagRagtime Nightingale Cleopatra Rag Reindeer 1916

Top Liner RagPatricia Rag 1919

Bohemia Rag |

c.1959

Brown Derby #2The Alaskan Rag The Beehive Rag The Jersey Rag Ragtime Reverie (19??) Chime In (192?) Crimson Rambler From Ragtime Treasures (©1964): Alabama Rag Arctic Sunset Bird Brain Rag Blue Grass Rag Chimes of Dixie Cottontail Rag Firefly Rag Good and Plenty Rag Hot Cinders The Old Home Rag Ragtime Bobolink Thoroughbred Rag Toad Stool Rag Lost or Mentioned in Text

All WetApple Sauce Banana Oil The Berries Brown Derby (#1?) Knick Knacks Ripples Shooting the Works Soup and Fish Sweet Pickles Waffle |

Songs, Marches and Waltzes Songs, Marches and Waltzes | |

|

1900

Idle Dreams †Meet Me at the Chutes † 1901

Mignonne-Valse LenteLenonah † 1902

Muskoka Falls-Indian Idyl[w/Bill Edwards - 2006] Dora Dean's Sister † 1903

Golden Leaves - Canadian Concert Waltzes †La Premier - French Canadian March † Midst the Valleys of the Far Off Golden West † When the Winter is Over † 1904

Lorne Scots on ParadeMy Queen of Zanzibar The Ivy Covered Homestead on the Hill † Tell Me Tha You Will Love Me as I Love You † 1905

Celestine WaltzesFlorida The Lilliputians' Bazaar The Eskimo Glide † Florida † A Rose and You † My Little Glow Worm † 1906

Red Feather - MarchFlorentine: Valse Sourdough March † 1907

Symphonic Syncopations (c.1907)The Lost Letter Sweet Nora Doone [1] 1908

Sunset-A Ragtime SerenadeThe Engineer's Last Good-Bye [1] I'm Jealous of You [1] She Doesn't Flirt [1] Somewhere a Broken Heart [2,3] In the Shade of the Maple by the Gate [2,4] Dear Blue Eyes: True Eyes [5] If Love is a Dream Let Me Never Awake [5] Love's Ebb Tide [5] Three Leaves of Shamrock on the Watermelon Vine [6] 1909

Gee, Kid! But I Like YouThe Homestead Where the Suwanee River Flows Love in Absence Dear Old Rose † 1910

I Love You Just the Same [8]My Fairy Iceberg Queen [8] Playmates [w/Will Wilander] |

1912

Let's Do It Again †1913

The Ladies' Aid Song [1]I Want to Be a Bird-Man [9] I'll Follow the Crowd to Coney [9] A Little Girl Like You † Romance Land † 1914

That Wonderful Melody †Wal-Yo [10] † 1915

I'd Give the World to Have You Back Again†Just for You † 1916

For the Cause of Liberty †Oh! You with Hair Like Mine † 1926

Love Me Like I Like You †1930

Purple Moon [11]So Here We Are [11] 1959

It Breaks My Heart ot Leave You,Melie Dear † 1960

Since You Took Your Heart AwayUnknown or Uncertain

Wanda †Only You † The 22nd Regiment March † Ilo Ilo † The Dying Hero † She's My Girl † I'd Like You to Love Me † I Should Have Known † Since You Took Your Heart Away † I'm Going to Go Somewhere † Don't You Be Lonely † Our Emperor/Our Empire † Menesis † Jennie: Song †† Farewell My Love †† Cheese It †† Down in Dear Old Florida †† In Gay Old Golden Gate ††

1. as Harry Moore

2. as Earl West 3. w/Samuel A. White 4. w/Ruth Dingman 5. w/Lynn Wood 6. as J. Lamb and H. Moore 7. w/Mary A. O'Reilly 8. w/Murray Wood 9. w/Mrs. G. Satterlee 10. w/Henrietta (Mrs. Joseph F.) Lamb 11. w/Gus Collins † Unpublished but Registered †† Listed by Ragtime Bob Darch |

Joe Lamb was born of Irish emigrant Catholic parents in Montclair, New Jersey, one of four children of James and Julia Lamb, including older siblings James Jr. (2/1872), Katharine (7/1878) and Annastesia (8/1884). He was schooled early on by his father in the carpentry trade along with his brothers. At age eight, Joseph received some informal piano and music lessons, the only real training he ever got from his older sisters who were both promising keyboard instrument players. Katharine was his most influential piano coach. Joseph also engaged in learning from the Etude magazine, a popular source for music at that time, which featured many classical works and some light popular pieces.

When Joe was just twelve, his father James died, and the teenager was subsequently sent to St. Jerome's College in Ontario for some engineering training. Throughout much of his time there Lamb was often homesick to the point where he threatened to walk home to New Jersey if his mother did not send him travel fare to get there. Enduring his time at the college, Joe could not keep the music bug out of his system, and even took lessons from a priest at the school.  However, these only lasted a few weeks as Joe had ascertained from his previous self-training and the assistance from his sister that the father had little to offer him. He also started composing while in Ontario, having been exposed to some of the German songs frequently performed in Berlin, not far from the school.

However, these only lasted a few weeks as Joe had ascertained from his previous self-training and the assistance from his sister that the father had little to offer him. He also started composing while in Ontario, having been exposed to some of the German songs frequently performed in Berlin, not far from the school.

However, these only lasted a few weeks as Joe had ascertained from his previous self-training and the assistance from his sister that the father had little to offer him. He also started composing while in Ontario, having been exposed to some of the German songs frequently performed in Berlin, not far from the school.

However, these only lasted a few weeks as Joe had ascertained from his previous self-training and the assistance from his sister that the father had little to offer him. He also started composing while in Ontario, having been exposed to some of the German songs frequently performed in Berlin, not far from the school.Lamb started composing almost as soon as he got to the school in 1900. His first entries were in popular genres, including an intermezzo, a song, and a waltz. One potential popular work, Muskoka Falls, was started when he was fourteen (and finished by the author in 2006).It was an obvious response to Charles Daniels' enormously popular Hiawatha of 1902. The name referred to a recreational resort area for the rich a bit north of Toronto. At one point the dormitory at the school was unavailable for a time, so he boarded at the Walper House in Kitchener, 50 or so miles west of Toronto, about which he also wrote one of his earliest rags. Most of his early pieces were non-ragtime, but some were published in Toronto as early as 1905, when he was but 17 years old, but likely submitted even earlier.

His time at the school was often quite frustrating, particularly given the separation from his family. He also got somewhat tired of the Germanic food that was frequently served there, the sauerkraut in particular. In an interview with Amelia Lamb by writer Eugene McCarthy in 1974, she recounts one rather jarring incident that occurred at the school. "Apparently in those days, the boys used to have to go without butter once a week but it was the custom that everyone took turns buying some on those days. One day, Joe was running back to school with the butter when he ran right into a brick wall and broke his nose."

Given that Joe's exposure to real ragtime was somewhat limited during his time in Canada, it underscores his musical sensibilities that he was able to turn out a piece of the quality of Walper House Rag in 1903, and a 1905 follow-up, Ragged Rapids Rag. Other unusual works included Celestine Waltzes and Lilliputian's Bazaar. Perhaps his most interesting early song was Three Leaves of a Shamrock, which discussed the difficult topic of miscegenation, in this case the marriage of a Irish man to a black woman. Most of these pieces were sold outright at low prices ($5 to $50) to publisher Harry H. Sparks in Toronto, simply because he wanted to see them in print. Most of these submissions were not published until well after Lamb had left Canada. Some were issued using the name of more classical and Germanic sounding Josef F. Lamb. As was a common practice of the time in an effort to boost the composers listed in a catalog, Lamb was also published under at least two other pseudonyms, Harry Moore and Earl West. He considered his relationship with Sparks more of a friendship than a business partnership, and made at least one visit to the publisher and his family sometime after he had left college.

Some were issued using the name of more classical and Germanic sounding Josef F. Lamb. As was a common practice of the time in an effort to boost the composers listed in a catalog, Lamb was also published under at least two other pseudonyms, Harry Moore and Earl West. He considered his relationship with Sparks more of a friendship than a business partnership, and made at least one visit to the publisher and his family sometime after he had left college.

Some were issued using the name of more classical and Germanic sounding Josef F. Lamb. As was a common practice of the time in an effort to boost the composers listed in a catalog, Lamb was also published under at least two other pseudonyms, Harry Moore and Earl West. He considered his relationship with Sparks more of a friendship than a business partnership, and made at least one visit to the publisher and his family sometime after he had left college.

Some were issued using the name of more classical and Germanic sounding Josef F. Lamb. As was a common practice of the time in an effort to boost the composers listed in a catalog, Lamb was also published under at least two other pseudonyms, Harry Moore and Earl West. He considered his relationship with Sparks more of a friendship than a business partnership, and made at least one visit to the publisher and his family sometime after he had left college.After Joe got a job working for a dry goods company in New York City at age 16, he never returned to school. At least some of his pay went towards weekly purchased of sheet music from local department stores, like Macy's and Gimbel's, and from publisher's outlets. He eventually ended up working for a publishing house in Manhattan, still composing on the side and getting small publication runs. In 1906 Joe started his own ragtime ensemble, the Clover Imperial Orchestra, which was kept mildly busy over the next five or so years playing for small gatherings such as church socials or lodge gatherings. Once publisher John Stark opened his own small store in Manhattan, Joe became a regular customer to the point that he was offered a discount for his frequency. It was there in 1907 that Joe had his fateful meeting with his idol, Scott Joplin.

Lamb had only recently been exposed to the classic rags of the "King of Ragtime," but quickly took to not only learning them, but emulating them in his own work as well. According to an interview with Joe recorded in 1958, he was in the publishing office of John Stark purchasing some of Joplin's more recent works in late 1907. Before leaving, he vocalized his wish to meet the master at some point, and the clerk pointed to a man with one leg wrapped up sitting across the room. "There he is." Lamb was enthralled, and after the accolades of admiration told Joplin that he had been writing ragtime too. So Joplin arranged for Lamb to play some of Joe's rags for him that evening (or soon after) at a gathering. Among the first pieces he played was his rag Sensation. By the time Lamb finished his performance the room full of Joplin's friends had gone quiet. Then, according to Joe, Joplin said, "That sounded like a good colored rag," which is exactly what Lamb had hoped to hear. Joplin arranged to have Sensation published by Stark, who paid the composer $25 with the promise of another $25 after the first thousand copies were sold. A second payment was indeed made a few weeks later, but nothing further for his first true sensation. Just the same, John Stark published pretty much anything Lamb sent him from that point on, even after the publisher retreated back to St Louis a couple of years later.

While Joe had written several pieces in 1908, including four rags, only Sensation was published at that time. It is unclear as to if he did not submit some of his pieces, like Dynamite Rag, or if Stark simply chose to not purchase them. Stark ended up publishing twelve of Joe's rags between 1908 and 1919, arguably his finest dozen to that point, but there would be more to come. His 1909 pieces were both standouts. Ethiopia was markedly different from Sensation, and perhaps created a new musical definition for the term Classic Ragtime that Stark had allegedly instantiated. But Excelsior not only offered proof of Joe's inherent musicality, but his persuasive personality as well. The Trio and D section of Excelsior was submitted in the key of Gb, complimentary to the opening key of Db. Given the difficulties of reading, and for some, playing in this key, Stark wanted to demur from printing those sections in that key, opting for Ab instead. However, Joe was adamant about the need to keep the original key because of the tonality it created. After he played the sections in both keys, Stark agreed, and it is one of the few rare pieces from the ragtime era that had a key signature of six flats within.

or if Stark simply chose to not purchase them. Stark ended up publishing twelve of Joe's rags between 1908 and 1919, arguably his finest dozen to that point, but there would be more to come. His 1909 pieces were both standouts. Ethiopia was markedly different from Sensation, and perhaps created a new musical definition for the term Classic Ragtime that Stark had allegedly instantiated. But Excelsior not only offered proof of Joe's inherent musicality, but his persuasive personality as well. The Trio and D section of Excelsior was submitted in the key of Gb, complimentary to the opening key of Db. Given the difficulties of reading, and for some, playing in this key, Stark wanted to demur from printing those sections in that key, opting for Ab instead. However, Joe was adamant about the need to keep the original key because of the tonality it created. After he played the sections in both keys, Stark agreed, and it is one of the few rare pieces from the ragtime era that had a key signature of six flats within.

or if Stark simply chose to not purchase them. Stark ended up publishing twelve of Joe's rags between 1908 and 1919, arguably his finest dozen to that point, but there would be more to come. His 1909 pieces were both standouts. Ethiopia was markedly different from Sensation, and perhaps created a new musical definition for the term Classic Ragtime that Stark had allegedly instantiated. But Excelsior not only offered proof of Joe's inherent musicality, but his persuasive personality as well. The Trio and D section of Excelsior was submitted in the key of Gb, complimentary to the opening key of Db. Given the difficulties of reading, and for some, playing in this key, Stark wanted to demur from printing those sections in that key, opting for Ab instead. However, Joe was adamant about the need to keep the original key because of the tonality it created. After he played the sections in both keys, Stark agreed, and it is one of the few rare pieces from the ragtime era that had a key signature of six flats within.

or if Stark simply chose to not purchase them. Stark ended up publishing twelve of Joe's rags between 1908 and 1919, arguably his finest dozen to that point, but there would be more to come. His 1909 pieces were both standouts. Ethiopia was markedly different from Sensation, and perhaps created a new musical definition for the term Classic Ragtime that Stark had allegedly instantiated. But Excelsior not only offered proof of Joe's inherent musicality, but his persuasive personality as well. The Trio and D section of Excelsior was submitted in the key of Gb, complimentary to the opening key of Db. Given the difficulties of reading, and for some, playing in this key, Stark wanted to demur from printing those sections in that key, opting for Ab instead. However, Joe was adamant about the need to keep the original key because of the tonality it created. After he played the sections in both keys, Stark agreed, and it is one of the few rare pieces from the ragtime era that had a key signature of six flats within.Joe Lamb is listed in 1910 as living with Catherine and his mother Julia, but his profession is that of a clerk for a dry goods company, although he is also known to have worked for music publisher J. Fred Helf around the same time as a song plugger. Researcher Joseph R. Scotti has speculated that this may have been a move of desperation or panic as Stark had vacated New York in 1910, returning to Missouri to care for his ailing wife. Joe later recalled with sadness a story concerning one of his submissions to Stark just before he left. It was Contentment Rag, and he had written to honor the publisher's marriage to his wife Sarah. However, Sarah died soon after this and the rag was subsequently not published until 1915 with a more generic cover than had originally been intended.

It was Contentment Rag, and he had written to honor the publisher's marriage to his wife Sarah. However, Sarah died soon after this and the rag was subsequently not published until 1915 with a more generic cover than had originally been intended.

It was Contentment Rag, and he had written to honor the publisher's marriage to his wife Sarah. However, Sarah died soon after this and the rag was subsequently not published until 1915 with a more generic cover than had originally been intended.

It was Contentment Rag, and he had written to honor the publisher's marriage to his wife Sarah. However, Sarah died soon after this and the rag was subsequently not published until 1915 with a more generic cover than had originally been intended.The composer was married in 1911 to his first wife, Henrietta Schulz. This is also when he moved away from Montclair and shortened his commute considerably. The newlyweds settled in at 615 Avenue C. in West Brooklyn, New York. Joe continued working in the dry goods, and also did some arranging for Helf as well, but in addition certainly turned in some of the best ragtime pieces ever written during the 1910's. Fortunately Stark continued to accept and publish these works. In 1913 Lamb raised the bar again with American Beauty, a rag full of lovely eight measure phrases and wide scoping melodies.

In 1914 Lamb got a steady job with the financing branch of an import business, L.F. Dommerich & Company, and from that point on music was relegated to the status of a serious hobby or avocation. Joseph F. Lamb Junior was born to the couple on July 23, 1915, around the time of the publication of the ambitious Ragtime Nightingale. This piece also had a personal history for the composer. Joe had been a fan of Ragtime Oriole by Missouri composer James Scott, who was also published regularly by Stark. Wanting to create his own bird call rag, Joe successfully attempted to fuse two classical pieces into a popular ragtime piece. Having kept some of his Etude magazines from earlier years, Joe took the bass line of the beginning of the Revolutionary Etude by Frederic Chopin and wrote his own lingering minor melody over a modified version of it. Henrietta After a lovely trio that emulated bird calls, he included a phrase from The Nightingale's Song by Ethelbert Nevin as a bridge back to the closing B section. The end result was what some have called the "lullaby of ragtime," and indeed Ragtime Nightingale (sometimes referred to as Nightingale Rag) still closes out many ragtime performances in the 21st century.

Henrietta After a lovely trio that emulated bird calls, he included a phrase from The Nightingale's Song by Ethelbert Nevin as a bridge back to the closing B section. The end result was what some have called the "lullaby of ragtime," and indeed Ragtime Nightingale (sometimes referred to as Nightingale Rag) still closes out many ragtime performances in the 21st century.

Henrietta After a lovely trio that emulated bird calls, he included a phrase from The Nightingale's Song by Ethelbert Nevin as a bridge back to the closing B section. The end result was what some have called the "lullaby of ragtime," and indeed Ragtime Nightingale (sometimes referred to as Nightingale Rag) still closes out many ragtime performances in the 21st century.

Henrietta After a lovely trio that emulated bird calls, he included a phrase from The Nightingale's Song by Ethelbert Nevin as a bridge back to the closing B section. The end result was what some have called the "lullaby of ragtime," and indeed Ragtime Nightingale (sometimes referred to as Nightingale Rag) still closes out many ragtime performances in the 21st century.The following year saw publication of one his best overall rags. Originally titled Cotton Tail, it was released by Stark as Top Liner Rag to accommodate cover art stock on hand. Lamb would later retool the piece as the richer and more refined Cottontail Rag, released in the mid-1960s after his death. Collectively they have been referred to as potentially the most perfect classic ragtime pieces ever composed. Top Liner was accompanied by the jaunty Patricia Rag. It should be noted that Joe simply liked the name, and that there was no direct relationship between the name of this rag and his daughter Patricia, who would be born in 1924.

Lamb's 1917 draft record shows him living in West Brooklyn and employed by Dommerich as a Custom House Clerk, with no mention of him as a composer or musician. In 1919 Stark published the last of the Lamb works that would appear in his catalog, the eclectic Bohemia Rag. Lamb died near the end of the great WWI flu pandemic on February 6, 1920, leaving him widowed with Joe Junior. For the 1920 census he was again listed not as a musician, but as a Bank Office Manager for Dommerich. Just the same, Joe was still composing, even if only to follow his own passions.

Joe married his second wife, Amelia Collins, on November 12, 1922. They remained in Brooklyn at 2229 East 21st Street, where Joe would live for the rest of his life. No longer submitting rags to Stark, he still wrote some rags and songs, but mostly kept them in a folder or trunk at home. Since he would take them out from time to time and retool them, it is hard to set a definitive origin or completion date on many of these works since they went uncopyrighted for so many years. Around 1923 or 1924 he was contacted to write some novelty piano pieces for Mills Music, one of the top publishers of that genre. One submission, titled Hot Cinders, was ultimately not published until after Lamb's death, but it stands up well to other novelties of the day. Among some other pieces mentioned, but lost at some point in the 1930s, were Ripples, All Wet, Chime In, and Soup and Fish.

Joe and Amelia had three children, including Patricia (2/6/1924), Robert (11/20/27), and Donald (7/18/1930). From around 1928 to 1935, Lamb was regularly involved with minstrel shows presented at St. Edmonds Catholic Church in Brooklyn. While he provided much of the material and participate in rehearsals, he evidently did not perform in these shows. The Lambs are shown in Brooklyn in 1930 as a family of six, including Joe Jr., Patricia, Richard and Robert. He was listed as a manager for an importing firm, which was likely Dommerich. Beyond that, little is known of his life in the 1930s except as remembered by his daughter Pat. She recalls that he did play the piano quite often at home, including his own pieces. While Pat recognized the pieces each time they were performed, and became quite familiar with them, she admits she didn't even know they had names until much later on. In some cases, they did not have names and had not even been notated, but some would eventually make it to manuscript paper. Joe also loved to regale his family with the now famous story about meeting Joplin, which they eventually got quite tired of, even if he did not.

While he provided much of the material and participate in rehearsals, he evidently did not perform in these shows. The Lambs are shown in Brooklyn in 1930 as a family of six, including Joe Jr., Patricia, Richard and Robert. He was listed as a manager for an importing firm, which was likely Dommerich. Beyond that, little is known of his life in the 1930s except as remembered by his daughter Pat. She recalls that he did play the piano quite often at home, including his own pieces. While Pat recognized the pieces each time they were performed, and became quite familiar with them, she admits she didn't even know they had names until much later on. In some cases, they did not have names and had not even been notated, but some would eventually make it to manuscript paper. Joe also loved to regale his family with the now famous story about meeting Joplin, which they eventually got quite tired of, even if he did not.

While he provided much of the material and participate in rehearsals, he evidently did not perform in these shows. The Lambs are shown in Brooklyn in 1930 as a family of six, including Joe Jr., Patricia, Richard and Robert. He was listed as a manager for an importing firm, which was likely Dommerich. Beyond that, little is known of his life in the 1930s except as remembered by his daughter Pat. She recalls that he did play the piano quite often at home, including his own pieces. While Pat recognized the pieces each time they were performed, and became quite familiar with them, she admits she didn't even know they had names until much later on. In some cases, they did not have names and had not even been notated, but some would eventually make it to manuscript paper. Joe also loved to regale his family with the now famous story about meeting Joplin, which they eventually got quite tired of, even if he did not.

While he provided much of the material and participate in rehearsals, he evidently did not perform in these shows. The Lambs are shown in Brooklyn in 1930 as a family of six, including Joe Jr., Patricia, Richard and Robert. He was listed as a manager for an importing firm, which was likely Dommerich. Beyond that, little is known of his life in the 1930s except as remembered by his daughter Pat. She recalls that he did play the piano quite often at home, including his own pieces. While Pat recognized the pieces each time they were performed, and became quite familiar with them, she admits she didn't even know they had names until much later on. In some cases, they did not have names and had not even been notated, but some would eventually make it to manuscript paper. Joe also loved to regale his family with the now famous story about meeting Joplin, which they eventually got quite tired of, even if he did not.Pat was actually given piano lessons starting in 1934 from an organist at their church. Even though she was clear with the teacher about the leanings of her mildly famous ragtime father, the teacher insisted on classical training and made it clear that Patricia should never play that ragtime type of music. It didn't stop her from doing that at home. After eight years of lessons Pat was able to play duets with her father, a fond memory of many fun evenings. Joe stayed involved in Pat's piano education, and even though he was flattered that she was playing his rags, he had no trouble with correcting her quickly if she went the wrong direction while playing one of them. The family spent part of each summer at a cabin in Vermont that Joe had purchased on the advice of a doctor, since the location was supposed to have been beneficial for the asthma suffered by one of Pat's brothers. The family would stay there and Joe would join them every other weekend or so. Joe and Amelia still had their children living with them according to the 1940 census, including Joe Jr., Patricia, Richard, Robert and Donald. He was listed simply as a factor manager, a brief but fairly accurate description of the job he so enjoyed.

In 1949 when They All Played Ragtime was being researched, authors, Harriet Janis and Rudi Blesh came to Brooklyn looking for the composer, trying to disprove a theory that he was simply a pseudonym for Scott Joplin. While the pair did not find Joe or Amelia at home, they did find Pat just up the street, and Rudi became quite excited when he confirmed that he had located the real Joe Lamb. They told her that they had combed the Midwest looking for him, but Joe knew right where he had been all these years.  They were able to secure an interview with Joe in short order, and he was one of the features of their book which was published in 1950. As a result of this pioneering effort, Lamb was soon sought out by many ragtime fans, both old and new. But he did not affect any particular changes to his life at that time. The 1950 census showed Robert, Donald and Mary still living with their parents, with Joe shown as a traffic manager for an iron works, a somewhat unexpected discovery.

They were able to secure an interview with Joe in short order, and he was one of the features of their book which was published in 1950. As a result of this pioneering effort, Lamb was soon sought out by many ragtime fans, both old and new. But he did not affect any particular changes to his life at that time. The 1950 census showed Robert, Donald and Mary still living with their parents, with Joe shown as a traffic manager for an iron works, a somewhat unexpected discovery.

They were able to secure an interview with Joe in short order, and he was one of the features of their book which was published in 1950. As a result of this pioneering effort, Lamb was soon sought out by many ragtime fans, both old and new. But he did not affect any particular changes to his life at that time. The 1950 census showed Robert, Donald and Mary still living with their parents, with Joe shown as a traffic manager for an iron works, a somewhat unexpected discovery.

They were able to secure an interview with Joe in short order, and he was one of the features of their book which was published in 1950. As a result of this pioneering effort, Lamb was soon sought out by many ragtime fans, both old and new. But he did not affect any particular changes to his life at that time. The 1950 census showed Robert, Donald and Mary still living with their parents, with Joe shown as a traffic manager for an iron works, a somewhat unexpected discovery.Joe retired from his financial career with Dommerich in 1957, a little after the time of his "rediscovery". It was then that he took a number of rags out of mothballs that had been composed from the late 1910s to more recent ones, and played them into a tape recorder on two different occasions for posterity. One session was for the benefit of a young Mike Montgomery who had just come back from Germany with his new reel to reel tape recorder and was warmly welcomed into the Lamb household for an evening concert by the composer. These late 1957 recordings were later released on a cassette, and they give an interesting look into how the composer approached his own pieces. Many of them were sight read on the spot, and as the evening progressed and Joe tired, he started to leave out repeats, and even picked up tempos a little bit. A second significant set of sessions, also done in his home, was recorded by historian Sam Charters on two dates in August 1959, and released on vinyl in 1968. This included some of his best conversations of recollections of the ragtime years. Lamb even performed for his first and only paid professional gig as a soloist at Club 76 in Toronto in late 1959 through the efforts of Bob Darch, John Arpin and others. It was on this evening that he made his only known recording of Hot Cinders, which is what Montgomery's cassette release was later named.

After a brief flurry of fame and widespread admiration, Joseph F. Lamb succumbed to a heart attack at home in 1960. Many of the unpublished rags were finally put into print in 1964 in the Belwin Mills folio Ragtime Treasures, adding to a great legacy of the potential beauty of ragtime realized for all of us. This folio, until recently owned by Warner Music, has now inexplicably been out of print since the early 1990s. However, they have now been made available once again, along with a couple of other recently discovered treasures found at OnlineSheetMusic.com. Fortunately, many other rags and interesting songs spanning his entire career were published, many for the first time, in 2005 through the efforts of his daughter Patricia Lamb-Conn, who is usually escorted to ragtime events by her supportive husband Bill Conn, and especially performer Sue Keller of Ragtime Press in Chicago, followed by Sue's premier recordings of many of these works, and the author's own completion of yet another one of them. Joseph Lamb is clearly never to be forgotten.

In terms of his legacy, Lamb's rags are still among the most played by those who are both discovering ragtime and those who have performed for a lifetime. Running with the best ideas of Joplin, he was able to develop even longer phrases throughout each section, with intricate harmonic balance in his chord progressions, and innovative use of inner melodic lines and complex syncopations as well. That he did so with as little musical training as he had, in addition to having grown up isolated from the mainstream of ragtime output and performance, makes his work all that more extraordinary. Lamb was also able to shape some fine songs and non-ragtime pieces. However, he will best be remembered by his ragtime output, a passion which kept him composing nearly to the end of his life.

I would like to add a personal note of thanks to Lamb's surviving daughter Patricia Lamb-Conn, ragtime performer/publisher Sue Keller and researcher Ted Tjaden, who variously provided additional family information and background along with discoveries and printing of many previously unknown Lamb pieces, some of which were still surfacing in 2008. Visit his site at ragtimepiano.ca/rags/lamb.htm to view some of the rare Lamb publications.

I also want to highly recommend Carol Binkowski's illuminating 2012 book, Joseph Lamb - A Passion for Ragtime, which is relatively widely available at the usual on-line suspects and some bookstores around the country.