|

Richard Cecil McPherson (Cecil Mack) (November 5, 1872 to August 1, 1944) | |

Compositions Compositions | |

|

1901

Don't Believe All You Hear, Honey [1]Miss Elegant [1] At Eventide [1] Good Morning Carrie! [1,2] Josephine, My Jo [3] Sons of Ham: Musical [4] (Royal) Sons of Ham Miss Hannah from Savannah The Leader of the Ball Good Afternoon, Mr. Jenkins Junie Elegant Darky Dan 1902

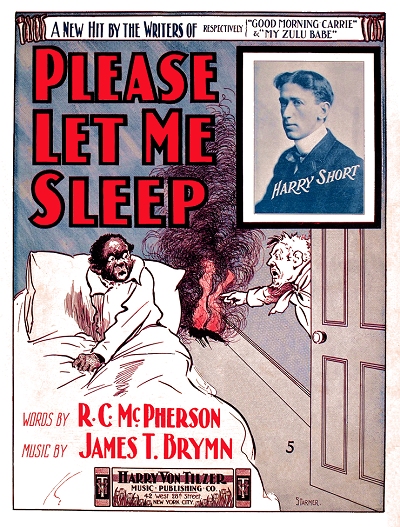

Please Let Me Sleep [3]By Wireless Telephone [3] Good Night, Lucinda [3] I Take Things Easy [3] Those Tantalizing Eyes [3] Don't Tell It To Me [3] The Little Gypsy Maid [5,6] She Did It All Herself [5,6] Molly Green [6] 1903

Look Into Your Baby's Eyes and SayGoo Goo [3] Brown Skin Baby Mine [6] Rosalyne [7] 1904

Zono, My Congo Queen [3]Send the Rent, and You Needn't Come Home [3] A Little Bit of Love and as Little Bit of Money [3] Prove It To Me [4] Slumber Song - Sweet Dreams, Dear One, of Me [6] Teasing [8] In a Birch Canoe [9] Goldie [9] Waltz Me, Charlie [9] I Guess It's Love [9] Let the Band Play and Irish Tune [9] We'll Raise the Roof To-Night [9,10] In the Shadow of the Pyramid [11] The Prettiest Gal in Borneo [11] 1905

Mandy Lou [6]Lula [6] 1906

He's a Cousin of Mine [1,12]All In Down and Out [1,2,13] Build a Nest for Birdie [3] When the Heart is Sad [4] 1907

It's Hard to Love Somebody (Who's LovingSomebody Else) [1] That's Where Friendship Ends [1] Just an Old Friend of the Family [1] The Candle and the Star [3,14] 1908

You're in the Right Church but the WrongPew [1] Down Among the Sugar Cane [1,15,16] Welcome to Our City: Rag Two-Step [17] For the Last Time, Call Me Sweetheart [18] 1909

Abraham Lincoln Jones, or The Christening [1]'Long In the Pumpkin Pickin' Time [1] Mammy's 'Lasses Candy Chile [6] 1910

If He Comes In, I'm Going Out [1]Never Let the Same Bee Sting You Twice [1] Porto Rico [3] That's Why They Call Me Shine [19] That Minor Strain [19] Way Down East [20,21] 1911

That Reuben Glide [20,22,23]1912

That Precious Little Thing Called Love: TheRiddle Song [1] There Ain't Nuthin' Doin' What You're Thinkin' About [1] Brand New! [1] Everybody Harmonize [1] The Last Shot Got Him - Blooey, Blooey, Blooey [1] 1913

Someone is Waitig Down in Tennessee [24]You Got to Rag It [25] Not To-night [25] |

1914

It's Great to Spoon to a Tango Tune [26,27]1915

Scaddle-De-Mooch: Novelty Song [1]My Country Right or Wrong [1] 1916

If You Don't Want Me, Send Me to My Ma [1]Down in Sugar Cane Lane [1] If I Were a Flower in the Garden of Love [1] Never Let the Same Bee Sting You Twice [1] I Want to Live and Die in Old Dixieland [6] 1918

Gal o' Mine (Caroline) [6]1923

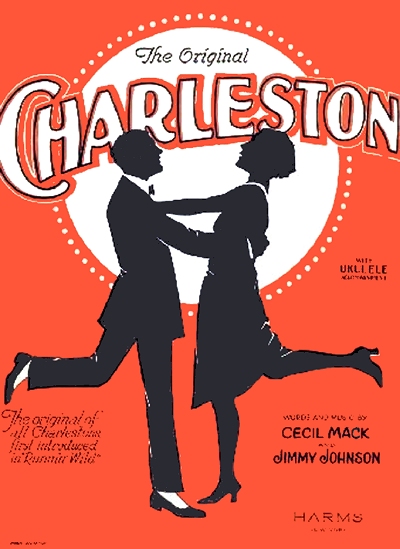

Runnin' Wild: Musical [28]Open Your Heart Ginger Brown Red Caps Cappers Old Fashioned Love Keep Moving (The Original) Charleston Roustabouts Log Cabin Days Ghost Recitative Pay Day on the Levee Song Birds Quatette Love Bug Juba Dance Jazz Your Troubles Away 1925

Fly Roun' Young Ladies [1]The Camel Walk [1,3,29] 1926

You for Me, Me for You From Now On [28]1936

My Cup [19,30]1937

Swing It: Musical [31,32]Jollification The Susan Belle and the Liza Jane What Do I Want with Love? Blah-Blah-Blah-Blah Ain't We Got Love? Old Time Swing Green and Blue By the Sweat of Your Brow I Believe Captain, Mate and Crew Farewell, Dixieland Sons and Daughters of the Sea Levee Ladies Huggin' and Muggin' The Conspirators Down with Frye I Praise Sue Spirit of Rhythm Jungle Swing/Jungle Love Rhythm is a Racket Swing Wedding

1. w/Chris H. Smith

2. w/Elmer Bowman 3. w/James Tim Brymn 4. w/Tom Lemonier 5. w/Harry B. Smith 6. w/Will Marion Cook 7. w/Fred F. Houlihan 8. w/Albert Von Tilzer 9. w/William J. Accooe 10. w/Sidney L. Perrin 11. w/Ernest R. Ball 12. w/Silvio Hein 13. w/Billy B. Johnson 14. w/J. Edward Green 15. w/Dan Avery 16. w/Charles Hart 17. w/Herman Carle 18. w/Louise A. Johns 19. w/Ford Dabney 20. w/Joe Young 21. w/Harold Norman 22. w/Jane Boynton 23. w/Bert Grant 24. w/James Reese Europe 25. w/William H. Farrell 26. w/Samuel S. Krams 27. w/Jack Von Tilzer 28. w/James P. Johnson 29. w/Bob Schafer 30. w/Sam Byrd 31. w/J. Milton Reddie 32. w/Eubie Blake |

Richard C. McPherson was one of the primary movers and shakers in terms of advocating for the rights of black performers and composers during the early part of the ragtime era, particularly through his efforts in getting them published and properly compensated in the white-dominated world of Tin Pan Alley. While he was primarily a lyricist, chances are good that he contributed some musical ideas to the pieces he helped pen, so is included here in that regard.

The birth year given for McPherson has gone through a number of variants over the years, with 1883 being the most common citation. However, the 1880 census showing him to be nine some seven months before his next birthday clearly suggests that not only was he alive well before 1883, but actually born as early as 1871, 1872 at the latest. For a number of reasons concerning his early movements, any birth year after 1875 (as he listed in the 1900 census) would make less sense. The mathematically suggested year of 1872 will be accepted for this essay as the most probable. Richard was one of two children born in Portsmouth, Virginia, to Henry McPherson and his wife Mary Louise, the other being his sister Eva (7/1882). The 1880 enumeration showed Henry to be a laborer, but within a few years he went into the undertaker business.

Richard was one of two children born in Portsmouth, Virginia, to Henry McPherson and his wife Mary Louise, the other being his sister Eva (7/1882). The 1880 enumeration showed Henry to be a laborer, but within a few years he went into the undertaker business.

Richard was one of two children born in Portsmouth, Virginia, to Henry McPherson and his wife Mary Louise, the other being his sister Eva (7/1882). The 1880 enumeration showed Henry to be a laborer, but within a few years he went into the undertaker business.

Richard was one of two children born in Portsmouth, Virginia, to Henry McPherson and his wife Mary Louise, the other being his sister Eva (7/1882). The 1880 enumeration showed Henry to be a laborer, but within a few years he went into the undertaker business.Richard's early education was from the Norfolk [Virginia] Mission School. Before he went for any advanced education, in February of 1891 at either age 17 or 18, Richard joined the Navy in Norfolk, likely as part of the support staff. His enlistment record showed him to be a waiter, and among his distinguishing marks he had "enlarged tonsils." After having saved up some money, he attended Norfolk Mission College in the mid-1890s, and then transferred to Lincoln University near Oxford, Pennsylvania, and Wilmington, Delaware, in 1898 or 1899. It was the first historically black university in the United States that granted accredited degrees. Richard also reportedly spent a semester at the University of Pennsylvania Medical School. He never obtained a degree from either institution. By this time Richard was spending his time away from the university in New York City, specifically trying to break into the music business. Among those that he made acquaintances with was vaudevillian Tom Lemonier, with whom he wrote some of his first songs.

The 1900 census creates a bit of a quandary in terms of identifying Richard. On June 2 he was enumerated at his parents' home near Norfolk, Virginia, but it is unclear if he was actually there or if that was what the enumerator was told. His mother, evidently suffering from a bout of vanity, gave her year of birth as 1872 (it was actually 1856), Eva's as 1883, and Richard - clearly added as an afterthought without any thought to logic - as 1880, making her eight at his time of birth. No career was listed for him, but Henry was shown to be an undertaker. On that same date in New York City, a Richard McPherson was also enumerated, black, born in Virginia, and working as a musician, living on 33rd street just blocks from what would soon be called Tin Pan Alley. This may be more of a coincidence than anything, since this Richard gave a birth year of 1870 but no month, and showed as married. The best and most accurate accounting of McPherson was actually his own, as he had taken on the job of enumerator for his section of Manhattan just off West 29th Street, where he was lodging. In that record, taken on June 12, he showed a November, 1875, birth, and his occupation was listed as a stenographer, which is logical, given that he had also been writing lyrics to Lemonier's music. In any case, he was clearly not 17 years of age as reported in many sources.

This may be more of a coincidence than anything, since this Richard gave a birth year of 1870 but no month, and showed as married. The best and most accurate accounting of McPherson was actually his own, as he had taken on the job of enumerator for his section of Manhattan just off West 29th Street, where he was lodging. In that record, taken on June 12, he showed a November, 1875, birth, and his occupation was listed as a stenographer, which is logical, given that he had also been writing lyrics to Lemonier's music. In any case, he was clearly not 17 years of age as reported in many sources.

This may be more of a coincidence than anything, since this Richard gave a birth year of 1870 but no month, and showed as married. The best and most accurate accounting of McPherson was actually his own, as he had taken on the job of enumerator for his section of Manhattan just off West 29th Street, where he was lodging. In that record, taken on June 12, he showed a November, 1875, birth, and his occupation was listed as a stenographer, which is logical, given that he had also been writing lyrics to Lemonier's music. In any case, he was clearly not 17 years of age as reported in many sources.

This may be more of a coincidence than anything, since this Richard gave a birth year of 1870 but no month, and showed as married. The best and most accurate accounting of McPherson was actually his own, as he had taken on the job of enumerator for his section of Manhattan just off West 29th Street, where he was lodging. In that record, taken on June 12, he showed a November, 1875, birth, and his occupation was listed as a stenographer, which is logical, given that he had also been writing lyrics to Lemonier's music. In any case, he was clearly not 17 years of age as reported in many sources.McPherson's earliest song collaborations were published by both Joseph Stern and the Shapiro, Bernstein and Von Tilzer firm in 1901, and were interpolated into the Bert Williams and George Walker show Sons of Ham. They did well enough that he abandoned his plans for a business or medical degree and entered the field of songwriting. His talent for subtle Negro dialect that did not perpetuate the stereotype of "coon songs" of the era helped to make his next number a lasting his. Good Morning, Carrie had music by Chris Smith and Elmer Bowman, and was among the first songs recorded by Williams and Walker in October of 1901. McPherson was quickly making friends with the other black songwriters in New York, and would collaborate with most of them in some way. It is very possible that one or more of them gave him his professional pseudonym, based on his middle name and part of his last, and by 1902 he was becoming known as Cecil Mack.

Among Mack's next hits were the comically clever Please Let Me Sleep composed with William and Walker's music director, James Tim Brymn, and The Little Gypsy Maid, written with Harry B. Smith and Will Marion Cook, who had already been making waves in the music world. Brymn, born in 1874 in North Carolina, was a graduate of Shaw University, then New York's Charlton Conservatory School of Music, and was considered to be a first rate pianist and overall musician. Both he and Cook regarded Mack's talent with lyrics, and wrote more pieces with him over the next couple of years, including two that were part of Cook's groundbreaking In Dahomey musical score introduced in 1903. Then in 1904, now consistently as Cecil Mack, he wrote some songs with lesser-known black composer William J. Accooe for interpolation into stage shows. Two other works were co-composed with famed white Irish balladeer Ernest R. Ball. Cecil next co-wrote the megahit Teasing with the white composer and publisher brother of Harry Von Tilzer, Albert Von Tilzer. It was issued by Albert's own York Music Company, which provided Cecil with a connection that soon put him in the publishing business with no less than Will Cook and his brother John.

Two other works were co-composed with famed white Irish balladeer Ernest R. Ball. Cecil next co-wrote the megahit Teasing with the white composer and publisher brother of Harry Von Tilzer, Albert Von Tilzer. It was issued by Albert's own York Music Company, which provided Cecil with a connection that soon put him in the publishing business with no less than Will Cook and his brother John.

Two other works were co-composed with famed white Irish balladeer Ernest R. Ball. Cecil next co-wrote the megahit Teasing with the white composer and publisher brother of Harry Von Tilzer, Albert Von Tilzer. It was issued by Albert's own York Music Company, which provided Cecil with a connection that soon put him in the publishing business with no less than Will Cook and his brother John.

Two other works were co-composed with famed white Irish balladeer Ernest R. Ball. Cecil next co-wrote the megahit Teasing with the white composer and publisher brother of Harry Von Tilzer, Albert Von Tilzer. It was issued by Albert's own York Music Company, which provided Cecil with a connection that soon put him in the publishing business with no less than Will Cook and his brother John.John H. Cook had followed his older brother Will to New York, and in 1904 saw an opportunity to help him out, and perhaps make some money in the process. Given Will's uneven temperament and his tenuous relationship with publishers and producers, he and some of his peers were clearly not getting the best possible deal for royalties or buyouts, particularly for hit shows. So John formed his own publishing company in the heart of Tin Pan Alley at 42 West 28th Street, which was also the current address for Harry Von Tilzer's company, and very near Albert Von Tilzer's distribution firm. Over the next several months of 1904, John published songs that were all by Will, including three from his next production, The Southerners, with lyrics by Harry Smith as Richard Grant.

However, the perception of John Cook's company as a vanity label for his brother was correct, and he sought to change that by expanding the scope and the stable of composers associated with him. Among them was Cecil, who had managed to work successfully with Will in the recent past. So in February of 1905 John incorporated his firm for $10,000 as Gotham Music, with Will Cook as the primary director, Richard McPherson as a partner (and the major financial contributor at the beginning), and club owner Barron D. Wilkins, who owned several black cabarets and bars in the Tenderloin district of New York, and also provided some solid financial backing and a presence the banks would be willing to work with. Among their first issues in their short life were two Bert Williams songs with lyrics by Earle C. Jones, as well as relabeled sheets of the songs from The Southerners. They added several more pieces, but in a haphazard fashion, with many of them lacking the quality found issued by other small publishers.

Less than four months in by the end of May, having already been dealt blows by court troubles and the lack of a clear hit to generate revenue, Gotham was looking to raise their profile a bit. They had good writers under contract, as did Attucks, but these writers also had contracts with theatrical companies who in turn were already set with Stern, Witmark, and other large firms. Composer and musician Shepard Edmonds had founded his own Attucks Music company just weeks before John H. Cook had set up his concern, and had a small but choice set of songs already in his catalog. However, following at least one lawsuit and some other personal challenges, Edmonds was looking to uncomplicate his life and turn a small profit. Gotham was looking for a profitable property, and it appears that the Bert Williams hit Nobody and other select pieces by black composers were enticing enough for McPherson, Cook and company to go forward with a merger/acquisition. It was announced in the New York papers on May 28, 1905, that, "The Gotham Music Company and the Attucks Music Company have consolidated and shall hereafter operate under the firm name of the Gotham-Attucks Music Company." By late July the ink was dry and they were in business, as per several notices in the music trades.

They had good writers under contract, as did Attucks, but these writers also had contracts with theatrical companies who in turn were already set with Stern, Witmark, and other large firms. Composer and musician Shepard Edmonds had founded his own Attucks Music company just weeks before John H. Cook had set up his concern, and had a small but choice set of songs already in his catalog. However, following at least one lawsuit and some other personal challenges, Edmonds was looking to uncomplicate his life and turn a small profit. Gotham was looking for a profitable property, and it appears that the Bert Williams hit Nobody and other select pieces by black composers were enticing enough for McPherson, Cook and company to go forward with a merger/acquisition. It was announced in the New York papers on May 28, 1905, that, "The Gotham Music Company and the Attucks Music Company have consolidated and shall hereafter operate under the firm name of the Gotham-Attucks Music Company." By late July the ink was dry and they were in business, as per several notices in the music trades.

They had good writers under contract, as did Attucks, but these writers also had contracts with theatrical companies who in turn were already set with Stern, Witmark, and other large firms. Composer and musician Shepard Edmonds had founded his own Attucks Music company just weeks before John H. Cook had set up his concern, and had a small but choice set of songs already in his catalog. However, following at least one lawsuit and some other personal challenges, Edmonds was looking to uncomplicate his life and turn a small profit. Gotham was looking for a profitable property, and it appears that the Bert Williams hit Nobody and other select pieces by black composers were enticing enough for McPherson, Cook and company to go forward with a merger/acquisition. It was announced in the New York papers on May 28, 1905, that, "The Gotham Music Company and the Attucks Music Company have consolidated and shall hereafter operate under the firm name of the Gotham-Attucks Music Company." By late July the ink was dry and they were in business, as per several notices in the music trades.

They had good writers under contract, as did Attucks, but these writers also had contracts with theatrical companies who in turn were already set with Stern, Witmark, and other large firms. Composer and musician Shepard Edmonds had founded his own Attucks Music company just weeks before John H. Cook had set up his concern, and had a small but choice set of songs already in his catalog. However, following at least one lawsuit and some other personal challenges, Edmonds was looking to uncomplicate his life and turn a small profit. Gotham was looking for a profitable property, and it appears that the Bert Williams hit Nobody and other select pieces by black composers were enticing enough for McPherson, Cook and company to go forward with a merger/acquisition. It was announced in the New York papers on May 28, 1905, that, "The Gotham Music Company and the Attucks Music Company have consolidated and shall hereafter operate under the firm name of the Gotham-Attucks Music Company." By late July the ink was dry and they were in business, as per several notices in the music trades.One of the first things that McPherson did to bolster the company, and perhaps to help fund and fight the accumulative lawsuits which eventually were dismissed or found to be in their favor, was to secure the best possible black talent to commit to the Gotham-Attucks brand. To that end, one of the early announcements was that Bert Williams and George Walker would be staff writers for the firm. Walker, who was more or less a stage talent but not a material contributor to the music, did not have much more to offer to the firm than his name. Williams, however, did write a few pieces, a couple of them r significant, that were published by Gotham-Attucks. Mack tried to acquire other talent as well, including Alex Rogers and Chris Smith, but in doing so he discovered the same conundrum that his predecessor Shep Edmonds had faced with Attucks - that of time spent as an administrator rather than as a musician. So in most of his first year at the helm of Gotham-Attucks, Cecil Mack found little or no time to contribute to any compositions. The 1905 New York State census showed McPherson, listed as a songwriter, living with his aunt Georgie Avendorth on 29th Street, just a couple of blocks from his new office.

Having managed to take care of the initial lawsuits pending when the company was merged, McPherson forged forward into 1906, but with little participation by Shep Edmonds who turned around and self-published a couple more of his own works. Mack teamed with Smith again, and over the next several years they would turn out a variety of clever songs that did moderately well. However, even with Albert Von Tilzer's assistance, they did not get the distribution necessary to take most of their material to a national stage. Their big hit for 1906 was He's a Cousin of Mine, which was taken up by the particular but even-handed Marie Cahill in her show Marrying Mary. Williams and Walker were among their best allies, and they recorded the Mack/Smith number All In, Down and Out from the musical Abyssinia that same year. Williams and Rogers came up with a successor to Nobody titled Let it Alone, but as it was a property suited to Bert's unique delivery, it had limited success for the firm.

Williams and Walker were among their best allies, and they recorded the Mack/Smith number All In, Down and Out from the musical Abyssinia that same year. Williams and Rogers came up with a successor to Nobody titled Let it Alone, but as it was a property suited to Bert's unique delivery, it had limited success for the firm.

Williams and Walker were among their best allies, and they recorded the Mack/Smith number All In, Down and Out from the musical Abyssinia that same year. Williams and Rogers came up with a successor to Nobody titled Let it Alone, but as it was a property suited to Bert's unique delivery, it had limited success for the firm.

Williams and Walker were among their best allies, and they recorded the Mack/Smith number All In, Down and Out from the musical Abyssinia that same year. Williams and Rogers came up with a successor to Nobody titled Let it Alone, but as it was a property suited to Bert's unique delivery, it had limited success for the firm.At the end of January, 1907, Gotham-Attucks faced yet another legal challenge. The firm of May & Harris, representing small publisher Morris Music, put legal rights to the moderate hit song He's a Cousin of Mine into receivership, claiming that they had sold a share of the piece to Gotham-Attucks, rather than an outright sale. The negative publicity did not help, as they kept referring Gotham-Attucks as a "colored" firm or one run by "colored managers." In the end, the action against Gotham-Attucks was decided in their favor for He's a Cousin of Mine, but battles like these required energy and money, which resulted in little net gain. Another continuing challenge in the company's efforts to remain vital came from established practices and alliances between theatrical producers and key publishers of Tin Pan Alley, which inhibited them from acquiring or retaining material. Cecil Mack and James Reese Europe wrote a score for Gus Hill in 1907 titled The Black Politician, starring the increasingly favored comedian S.H. Dudley. This was the first complete score that Mack had been involved with, and presented a good opportunity for Europe, who would soon have a prestigious command of sorts over the black musicians of New York. However, Mack's own firm was not able to get publication rights for his own work, as Hill had engaged Will Rossiter, "The Chicago Publisher," to take on at least five of the pieces, likely in exchange for some financial assistance with staging the production.

Even with their collective involvement, Williams, Smith, and even the difficult Cook, had standing contractual arrangements with other publishers and quotas to fill, so they could not always supply good content for their own concern. Other black composers who were friends and associates of the directors ended up having nothing to offer Mack and his company, including Irving Jones, Bob Cole, Ernest Hogan, Al Johns, and their founding father, Shepard Edmonds. The result was an average of ten pieces per year issued by Gotham-Attucks, in contrast to the 150 to 2,000 publications put out annually by other Tin Pan Alley firms.

Only the stalwart E.T. Paull was issuing less, but his reputation and colorful covers kept his firm profitable. The larger firms were also more enticing to black writers, since they had the resources and personnel to plug their works (although often by masking the race or gender of their writers) both to the public and to vaudeville and theatrical performers. The lack of profitability even made advertisements in trade papers or general newspapers difficult, and they often had to depend on plugs and announcements, as well as their promotional material on the back covers of Gotham-Attucks sheets.

|

While the late 1907 musical Bandanna Land by Shipp, Rogers, Cook and Williams offered some hope through minor hits that Mack was able to retain, in addition to an interpolation of Nobody for a second round of sales, the only notable piece from that production was the comically salacious Mack/Smith number, You're in the Right Church But the Wrong Pew. This helped to make 1908 a slightly better year, and they even felt confident enough to move from 28th street to a location closer to the major theaters, 136 West 37th Street. Another promotional vehicle was the formation of The Frogs (pictured left), founded by Williams and Walker, and made up of the leading black composers and performers of New York during that year, although with the conspicuous absence of independently-minded Will Cook. Mack was the first secretary of the organization, headed by George Walker and John Rosamond Johnson. While not directly beneficial to Gotham-Attucks, just the mention of the composers' names in the reports of various functions they held or appeared at was a peripheral form of publicity. They soon expanded the esteemed group to include professionals from other high-profile fields as well. Still, it was not quite enough to be of much help to the struggling firm.

Mack admitted to a trade paper in early 1909 that Gotham-Attucks was not doing as well as he had hoped, but that the best was yet to come. They had been actually giving away arrangements for band and orchestra, hoping that theatrical performances would turn into sales. (This practice plus that of professional copies was widely debated amongst publishers over the next several years, and eventually all but banned by most of them, who started charging even for samples.) Their forward progress was impeded by the virtual loss of one of their stars and best promoters, George Walker, who had spent the past decade on stage with Bert Williams. He had suffered from tertiary syphilis, and the disease wore him down to the point where he finally had to withdraw from Bandana Land, and finally from any stage work. For a time, his wife, Aida Overton Walker, took over in his roles, singing the same hit songs. So they had to look elsewhere for their stars.

Gus Hill produced another show in 1909 that was largely penned by Brymn and Smith, with some lyrics by Mack. His Honor the Barber presented Mack and Gotham-Attucks with the ongoing challenge of letting the firm issue their own material, as Hill offered many of the pieces to Joseph Stern, including the comical Come After Breakfast, Bring 'Long Own Lunch, and Leave 'Fore Supper Time. However, another lasting hit that would endure long after the death of its composers, Cecil and newcomer Ford Dabney, was That's Why They Call Me Shine, albeit in later years with less race-centric lyrics. Shine, which was sung in the show by George Walker's wife, Aida Overton Walker (filling in for her ailing spouse), was the major money-maker of 1910 for Gotham-Attucks, and helped to elevate Dabney as a competent composer. Both he and Europe had become the key directors of New York's stellar musical organization, The Clef Club. It was made up of all of the finest musicians of color from New York and surrounding areas, and through concerts they became known as the go-to source for the best possible music for events held by the richest of the rich, New York City's "400," comprised of the most prosperous New York families.

as Hill offered many of the pieces to Joseph Stern, including the comical Come After Breakfast, Bring 'Long Own Lunch, and Leave 'Fore Supper Time. However, another lasting hit that would endure long after the death of its composers, Cecil and newcomer Ford Dabney, was That's Why They Call Me Shine, albeit in later years with less race-centric lyrics. Shine, which was sung in the show by George Walker's wife, Aida Overton Walker (filling in for her ailing spouse), was the major money-maker of 1910 for Gotham-Attucks, and helped to elevate Dabney as a competent composer. Both he and Europe had become the key directors of New York's stellar musical organization, The Clef Club. It was made up of all of the finest musicians of color from New York and surrounding areas, and through concerts they became known as the go-to source for the best possible music for events held by the richest of the rich, New York City's "400," comprised of the most prosperous New York families.

as Hill offered many of the pieces to Joseph Stern, including the comical Come After Breakfast, Bring 'Long Own Lunch, and Leave 'Fore Supper Time. However, another lasting hit that would endure long after the death of its composers, Cecil and newcomer Ford Dabney, was That's Why They Call Me Shine, albeit in later years with less race-centric lyrics. Shine, which was sung in the show by George Walker's wife, Aida Overton Walker (filling in for her ailing spouse), was the major money-maker of 1910 for Gotham-Attucks, and helped to elevate Dabney as a competent composer. Both he and Europe had become the key directors of New York's stellar musical organization, The Clef Club. It was made up of all of the finest musicians of color from New York and surrounding areas, and through concerts they became known as the go-to source for the best possible music for events held by the richest of the rich, New York City's "400," comprised of the most prosperous New York families.

as Hill offered many of the pieces to Joseph Stern, including the comical Come After Breakfast, Bring 'Long Own Lunch, and Leave 'Fore Supper Time. However, another lasting hit that would endure long after the death of its composers, Cecil and newcomer Ford Dabney, was That's Why They Call Me Shine, albeit in later years with less race-centric lyrics. Shine, which was sung in the show by George Walker's wife, Aida Overton Walker (filling in for her ailing spouse), was the major money-maker of 1910 for Gotham-Attucks, and helped to elevate Dabney as a competent composer. Both he and Europe had become the key directors of New York's stellar musical organization, The Clef Club. It was made up of all of the finest musicians of color from New York and surrounding areas, and through concerts they became known as the go-to source for the best possible music for events held by the richest of the rich, New York City's "400," comprised of the most prosperous New York families.In spite of the growing success of That's Why They Call Me Shine, it was clear that Gotham-Attucks could not survive on the income from just a few works. Even its most ardent champions were going elsewhere in order to make a respectable amount from their newest compositions, or at least see the distributed more effectively around the country. Smith and Williams were among the more evident defectors, and along with Smith at times was the company's director, Cecil Mack, who had to admit to the trouble in his firm. In spite of the roles of Will and John Cook in getting Gotham-Attucks launched, even Will had his latest 1910 hit, Lovie Joe, published by Harry Von Tilzer. These firms could count on volume, knowing that the occasional hit would counter any flat sales by other pieces, but Gotham-Attucks simply did not have that advantage. The 1910 enumeration showed McPherson lodging not all that far from his office, and listed as a music publisher, albeit with more than a half-decade trimmed from his actual age.

Cook was largely disengaged from Gotham-Attucks by 1911, and as virtually all of his publications from that time were issued by Harry Von Tilzer, he was no longer a financially viable part of the company, which was largely run by Mack at this point. As he was more or less the last surviving member of Gotham-Attucks, Cecil finally threw in the towel in mid-1911. He held a fire sale of the company's major copyrights, most of which went to a company he had done with business with for a decade, Joseph Stern. Remaining properties were later purchased by the Robbins-Engel firm. Both companies reissued songs like Shine and Nobody separately, but most of the rest of them in folios, generating at least minimum income, albeit not for their originators. Surprisingly, Mack and Wilkins did not simply dispose of the firm, but sold off the name and the office space to another investor looking for an existing property. In hindsight, it turned out to be an unfortunate move and created a less than respectable end to a firm that had been founded with good intentions and optimism just six years prior. It was run into the ground over the next year by white composer Ferdinand Mierisch, who used the name to solicit music and lyrics for publication at a price, a practice later referred to as song sharking. Mierisch ended up abandoning the firm in mid-1912, and actually went on to write pieces with Smith, Mack, and others over the next two years, which belies the traditional story that he was dishonorable, suggesting only that he was a bad manager with questionable motives.

McPherson, continuing to write as Cecil Mack, contributed to several more pieces with Chris Smith though part of the 1910s. The pair even had a few key pieces placed with the Ziegfeld Follies, an important platform for many songwriters, and the organization where Bert Williams, now working alone, found success in his last few years. Shine continued to find favor with many interpolations, recordings, piano rolls, and live stage renditions, albeit through publisher Shapiro & Bernstein. Already having been in the Navy in the 1890s, Mack appeared to have at least signed up for service in 1918 with the New York Guard's 16th Infantry. He was relieved of duty on March 20, 1919, and resigned from the guard in October of 1926 with the rank of 2nd Lieutenant. Cecil married Gertrude E. Curtis in 1912 shortly after having broken free of Gotham-Attucks, and she became (reportedly) the first black female dentist in the United States. He may have considered retirement from music briefly, as the 1920 census taken in Harlem showed Gertrude running a dentist office in their home, and Cecil as a manufacturer of dental supplies.

He was relieved of duty on March 20, 1919, and resigned from the guard in October of 1926 with the rank of 2nd Lieutenant. Cecil married Gertrude E. Curtis in 1912 shortly after having broken free of Gotham-Attucks, and she became (reportedly) the first black female dentist in the United States. He may have considered retirement from music briefly, as the 1920 census taken in Harlem showed Gertrude running a dentist office in their home, and Cecil as a manufacturer of dental supplies.

He was relieved of duty on March 20, 1919, and resigned from the guard in October of 1926 with the rank of 2nd Lieutenant. Cecil married Gertrude E. Curtis in 1912 shortly after having broken free of Gotham-Attucks, and she became (reportedly) the first black female dentist in the United States. He may have considered retirement from music briefly, as the 1920 census taken in Harlem showed Gertrude running a dentist office in their home, and Cecil as a manufacturer of dental supplies.

He was relieved of duty on March 20, 1919, and resigned from the guard in October of 1926 with the rank of 2nd Lieutenant. Cecil married Gertrude E. Curtis in 1912 shortly after having broken free of Gotham-Attucks, and she became (reportedly) the first black female dentist in the United States. He may have considered retirement from music briefly, as the 1920 census taken in Harlem showed Gertrude running a dentist office in their home, and Cecil as a manufacturer of dental supplies.With the exception of one published work, which may have been a leftover from an earlier year, McPherson appears to have not written anything from 1917 through 1922. However, either the lure of the stage or requests from other composers put him back into world of music, and to no small effect either. Paired up with younger writers in the early 1920s, Mack found renewed success when he co-wrote the Broadway musical Runnin' Wild with James P. Johnson in 1923. The key hit from that production, albeit more as an instrumental than a song, was part of the essential soundtrack of the so-called "Jazz Age" of the 1920s: The Charleston. However, another gem from that show that is still played nearly a century later was Old Fashioned Love, a wonderful lilting song touched with a bit of stride. He also wrote again with Chris Smith in 1925.

Even though he was more lyricist than composer, Mack still had a keen musical sense, which put him in the position to work with white producer Lew Leslie starting in 1928 and continuing into the early 1930s, for productions of Leslie's Blackbirds. These revues starred, and in some cases launched the careers of many famous black stars. Among them were Bill "Bojangles" Robinson and Florence Mills. Cecil worked as Leslie's show choir director. The 1930 enumeration taken in Harlem also showed that he was a magazine writer, contributing to a few black-centric publications. Although he found only scant work in music during the Great Depression following his stint with Leslie, Mack was teamed with composers Eubie Blake and J. Milton Reddie in 1937 for a government-funded WPA production of a show named Swing It. Now in his mid-sixties, Mack more or less retired at that time. Still, the 1940 census showed him to be a writer for a music company. When World War II broke out, Cecil signed up to work with the selective service board during the initial draft process in early 1942. He eventually passed on in his Harlem home in the summer of 1944 at age 71 following six weeks of illness. In obituaries he was remembered for his role in Gotham-Attucks, a company that clearly would not have made it even for the six years it lasted without his leadership and determination.