Percy Wenrich (January 23, 1880 to March 17, 1952) | |

Compositions Compositions | |

|

1897

L'Inconnu1903

Ashy AfricaJust Because I'm From Missouri Wenonah: Intermezzo 1904

Dance of the Daisies [1]Why Don't We Make Love Like the White Folks Do? [2] The Sun Shines on No Sweeter Girl than You [3] 1905

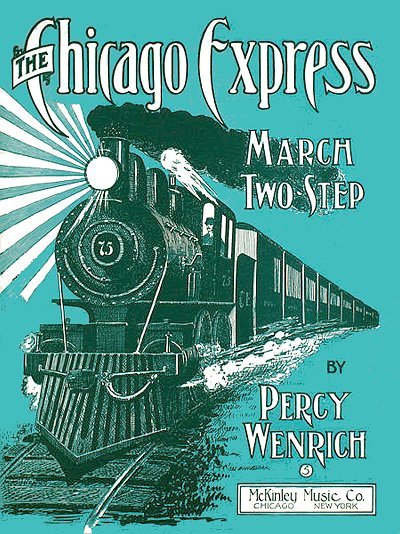

Dance of the Wild FlowersChicago Express-March Peaches and Cream Valse Tranquil Mexicana Dance of the Merry Legs [2] Down in Blossom Row [2] What's the Matter with the Mail? [2] I Don't Want No Imitation Man [2] My Mama's Waiting There [4] Good-Bye, Mary Dear [4] Wabash Avenue After Dark [5] 1906

Chestnuts: Rag MedleyDixie Blossoms Sonora: Spanish Novelette Home Sweet Home and Annie Laurie (Ragtime Arrangement) Moon Kisses: Three-Step Noodles: A German Rag In Honey-moon Valley With You [3] Made In Germany [6] 1907

Bom-Bay: An East Indian OddityDixie Darlings Flower Girl: Intermezzo March The Smiler: A Joplin Rag Fun-Bob The Fireman's Dream: Descriptive March Bachelor's Button: A Garden Dance Georgia Jingles: A Jingley Two-Step Sweetmeats: Rag Two-Step My Old Black Joe Fairy Queen: Intermezzo Two-Step Wedding Bells: Waltzes Morning Glories [1] Fighting the Flames [1] Golden Twilight [1] Flowers of Spring [1] Under the Tropical Moon [3] I'm Savin' Up My Money for a Rainy Day [3] A Girl Like You Would Do for a Boy Like Me to Woo[3] Fairy Queen: Song [7] If I Only Knew You Better [7] 1908

Dixie KicksAuto Race: March and Two-Step Crab Apples: Rag Two-Step The Memphis Rag: Two-Step Lilac Blossoms: Two-Step Happy Hours: Barn Dance Ragtime Ripples Persian Lamb Rag: A Pepperette Wild West: Cowboy-Indian Intermezzo Blushes: Novellette Rainbow: An Indian Intermezzo Dance of the Nymphs By A Garden Gate: Novelette Take Me Some Place, Will You, Willie? [2] Get Under My Parasol [2] When the Girl You Think the World Of Thinks the World and All of You [2] Maid of Heatherbloom [2] Maid in Blue [2] Don't You Think That You Could Learn to Love Me? [3] Rose-Buds: Intermezzo [8] My Dearie (Ma Chérie) [8] Sunflower Tickle [9] Naughty Eyes [10] I Didn't Ask, He Didn't Say, So I Don't Know [11] Under the Evening Star [12] Rainbow (Come, Be My Rainbow) [13] It's Moonlight All the Time On Broadway [14] The Recipe for Love [14] Up in My Balloon [14] If It's Good Enough for Washington, It's Good Enough for Me [14] Just Because I've Learned to Love You [15] I Am Going Far Away [16] When the Nightingales are Singing Ula Dear [17] Heathen Japan [18] 1909

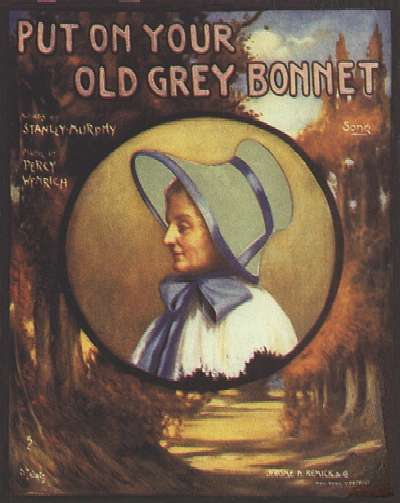

Soda WaltzBoy's Brigade: March Cotton Babes Dublin Daisies: An Irish Intermezzo Across the Ocean: Descriptive March Westward Ho!: March and Two-Step Jungle Moon: Intermezzo and Two-Step Mandy, How Do You Do? Jungle Moon: Song [3] Dublin Daisies: Song [13] The Baltimore Bombashay [19] Put On Your Old Grey Bonnet [19] Dixie Darling: Song [20] 1910

Egyptian RagSilver Bell: Intermezzo Show Folks: March We've Kept the Golden Rule: March Roosevelt March Open Your Eyes A Southern Symphony: Rag (Opus 7-11) I'll Meet You When the Sun Goes Down Zu-Zu [3] I'm a Lucky Boy to Have a Girl Like You [19] Sugar Moon [19] Macaroni Joe [19] That Loving Two-Step Man [19] Take Your Hats Off to Old Ireland [19] Tony Martell [19] She Took Mother's Advice [19] That Lovin' Two-Step Man [19] We've Kept the Golden Rule: Song [21] Alamo Rag [21] Silver Bell: Song [22] Show Me the Way to Loveland [23] All Over Town [24] 1911

Rag Time ChimesDancing Wavelets: Three-Step Catnip: Characteristic Two-Step Pop Corn Dance: Schottische In Teepee Land Sunflower Rag Golden Deer: Intermezzo Down in Old Arkansas: Two-Step Montana Girl: Two-Step Silver Leaf: Waltz Happy Hours: Reverie Morning in the Mountains: Idyll Irish Beauties: Two Step Free Masons March Red Rose Rag [22] In Old Ireland Where the River Kenmare Flows [22] The Skeleton Rag [22] A Hot Time in Monkey Town [22] Spanish Eyes [22] My Hula-Hula Love [22] I've Got Feathers On My Head [22] We Loved Each Other in the Long Ago [22] I'm Lonesome for Somebody Who Loves Me [25] That's the Kind of Fellow That I Could Love [26] 1912

Clover Land: Intermezzo Two-StepWhipped Cream: A Rag After a While [22] Moonlight Bay [22] Rag Time Chimes: Song [22] Kentucky Days [27] Buddy Boy: Novelty Rag [27] Shamrock Belles [27] Tennessee Moon [27] Let's Stroll in the Garden of Dreams [27] Don't You Worry Dearie [28] Golden Deer: Song [29] 1913

Pennant RagDimples [22] Snow Deer: Indian Song [27] I'll Just Follow You [27] I Miss My Mississippi Man [27] When You're Living in a College Town [27] Save a Couple for Father [27] That's Why the Rose Never Dies [27] Somebody's Eyes [27] Peaches [27] Good-Bye Summer! So Long Fall! Hello Wintertime [27] When It's Moonlight in Mayo: Song [27] The Fascinating Widow: Musical Cute in My Bathing Suit [30] Jack-O'-Lantern Moon [27,30] The Fascinating Widow [27,30] Hindoo [27] Ragtime College: Turkey Trot [27,30] 1914

The Weeping Willow: One-StepWay Out Yonder in the Golden West When You Wore a Tulip (And I Wore a Big Red Rose) [27] Cotton Blossom Time [27] The Crinoline Girl: Musical [30] In My Dream of You Game of Eyes When Martha Was a Girl That Tempting Tango 1915

Come Back, Dixie: One-StepWhen It's Moonlight in Mayo: Waltz In the Glory of the Moonlight Come Back, Dixie [27] Summer Love, It's the Same Old Game [27] A Girl in Your Arms is Worth Two in Your Dreams [27] Mothers Must Pay for All [27] Wabash Avenue After Dark [31] 1916

Twilight Memories: MeditationSteeple-Chase Fox-Trot |

1916 (Cont.)

Silver BayI've Loved Only Once [32] Cousin Lucy: Musical [22] Mam'selle Lucette Sweetheart When You Skate With a Wonderful Girl Everybody do the Hula The Bride Tamer: Musical [33] Behold Our Home Oh Father, Dear Father Buffet Song I'll Tra La La La La She Locked Me Out Now I'll Unlock the Door 1917

Where Do We Go From Here?: MarchOn the Party Line [27] Where is the Girl You Had Last Night? [27] You'll Always Be Sweet Sixteen to Me [27] Where Do We Go From Here, Boys? [34] Sweet Cider Time, When You Were Mine [34] We Were Pickin' Berries at Old Aunt Mary's In Berry Pickin' Time [35] When I'm Through with the Arms of the Army (I'll Come Back to the Arms of You) [36] 1918

A Rainbow from the U.S.A. [27]My American Hitchy Koo Girl [27, 37] It's Kentucky First, Ketnucky Last, Kentucky All the Time [27,37] I Ain't Got Weary Yet [34] You Can Tell That He's An American [34] 1919

By the Campfire: SoloOne Loving Caress: A Love Waltz How Are You Going to Wet Your Whistle (When the Whole Darn World Goes Dry?) [38,39] I Wish I Had Somebody Waiting for Me When I Got Home [40] By the Camp Fire: Song [41] Casey (K.C.) [42] 1920

Maid to Love: Musical [43] (©1919)The Things I Learned in Dear Old Jersey Girls All Around Me Aladdin Love is Calling Say Something Sweet to Me Love's Little Journey Oriental Serenade Dancing to the Tune of Love Love's Romantic Sea 1921

I Want a Picture of YouHoney Love [43] Minnetonka [44] The Bobbed-Hair Babies Ball [45] The Right Girl: Musical [43] (©1919/1920) Cocktail Hour You'll Get Nothing from Me Call of Love We Were Made to Love Old Flames The Rocking Chair Fleet Love's Little Journey Harmony Look for the Girl Aladdin Lovingly Yours The Right Girl 1922

Chasing the Fox: Fox TrotRustic Ann Keep On Building Castles in the Air All Muddled Up Silver Stars September Days Love's Telephone Moonlight Lullaby The Nineteenth Hole [38] Baby [43] 1923

When the Shadows FallDreams of India Nonsense Chinky Under the Maples My Darling Lindy Lady: Fox Trot Lindy Lady: A Southern Mellow Moon Song Goodbye Dobbin [34] Barefoot Boy [44] 1924

In the Purple TwilightBurning Kisses [43] 1925

Mr. Mulligan and Mr. GarrityYou Better Keep the Home Fires Burning (Cause Your Mamma's Getting Cold) [46] Castles in the Air: Musical [43] Love's Refrain I Don't Blame 'Em Lantern of Love [w/Edward Locke] The Singer's Career, Ha! Ha! The Other Fellow's Girl If You Are in Love With a Girl Baby The First Kiss of Love The Sweetheart of Your Dreams I Would Like to Fondle You The Rainbow of Your Smile Latavian Folk Song Land of Romance My Lips, My Love, My Soul! Girls and the Gimmies Love Rules the World 1927

San Fairy Ann [38]The Bells of San Gabriel's [48] 1928

Tinkle ToesWhen Your Old Grey Bonnet was New [27] Guatemala Melody [49] 1930

By the Old Oak TreeThe Girl I Left Behind Me Hail to the Gleaner Baldwin [25] Who Cares: Musical [50] Nobody But You Who Cares? Your Way Will Be My Way Make My Bed Down in Dixieland 1932

Okay! Beer and Better Times Will Soon BeHere [51] 1933

Pale MoonlightThe Flow'rs in Spring 1937

Sail Along, Silv'ry Moon [52]Enchanted Isle and Avalon [53] The Grass is Growing Greener All Around [54] 1939

Any Place is Heaven Whenever You'reAround [52] Forget Me Not in Remember Me Lane [52] Something Old, Something New [55] 1940

Yosemite (Ahwahnee) [56]1946

SerenadeCrimson Waters Missouri, My State! Let's Wear Our Whiskers Long [57]

1. as Earl La Farge

2. w/Fred J. Hamill 3. w/C.P. McDonald 4. w/Frank W. Stearns 5. w/James O'Dea 6. as Karl Schmidt 7. w/Elmore I. Lee 8. as Eugene La Farge 9. as Dolly Richmond 10. w/Harry Sylvester 11. w/Tom Farrel 12. w/Sam Ehrlich 13. w/Alfred Bryan 14. w/Ren Shields 15. w/Morris S. Silver 16. w/Ollie Dyer 17. w/J.H. Reed 18. w/Henry H. Harrison 19. w/Stanley Murphy 20. w/Arthur Gillespie 21. w/Ben Deely 22. w/Edward Madden 23. w/Beth Slater Whitson 24. w/Al Trahern 25. w/Dolly Connolly 26. w/Albert Gumble 27. w/Jack Mahoney 28. w/Al W. Morse 29. w/Harry Williams 30. w/Julian Eltinge 31. w/James O'Dea 32. w/Carl Randall 33. w/Edgar Allan Wolff 34. w/Howard Johnson 35. w/Jack Yellen 36. w/Earl Carroll 37. w/William Jerome 38. w/Frank McIntyre 39. w/Francis Byrne 40. w/Howard E. Rogers 41. w/Mabel Elizabeth Girling 42. w/John B. Kennedy 43. w/Raymond W. Peck 44. w/Gus Kahn 45. w/John W. Bratton 46. w/Edgar Leslie & Charles Kinney 47. w/Edward Locke 48. w/J. Keirn Brennan 49. w/L. Wolfe Gilbert 50. w/Harry Clark 51. w/Charles Tobias, Sidney Clare, Vincent Rose, Al Sherman, Murry Mencher, Al Lewis 52. w/Harry Tobias 53. w/Walter C. Vall, Chris Mann 54. w/Jack Meskill 55. w/O. Millard Smith 56. w/William J. Palmer 57. w/T. Cowgill |

It was clear from an early age that Percy Wenrich (pronounced Wen-rik - no middle name) had a true gift for melody. He was born in Missouri to Daniel Wenrich and Mary Ray in 1880. A few documents show minor variations to this—seven years in some cases—and some mistakenly showing June instead of January—but the most accurate of them point consistently to January, 1880, as the proper birth month and year, including the 1880 census. In that record, Daniel was listed as a lead miner, but his career track soon changed for the better. Percy had four siblings, including Raymond (9/1877) and Nellie (4/1890). The other two, born in the 1880s, had died in childhood before 1900.

Wenrich was raised in Joplin in southwest Missouri, surrounded by classic and folk ragtime influence. His father became the postmaster of the growing city, and his first piano and organ teacher was his mother, an amateur pianist and organist in her own right. According to Wenrich she was known as "the Berry County pianist." In fact, Percy's siblings also learned to play piano to some capacity.

According to Wenrich she was known as "the Berry County pianist." In fact, Percy's siblings also learned to play piano to some capacity.

According to Wenrich she was known as "the Berry County pianist." In fact, Percy's siblings also learned to play piano to some capacity.

According to Wenrich she was known as "the Berry County pianist." In fact, Percy's siblings also learned to play piano to some capacity.In his early teens he started writing his own melodies, collaborating for fun with his father who penned or even improvised on-the-spot lyrics for them. Some of them actually made their way into public performances and special events through the elder Wenrich's official capacity in the local Republican Party. According to a September 7, 1949 Billboard Magazine article, "These songs eulogized such Democratic stalwarts as Grover Cleveland and William Jennings Bryan, and were sung at political rallies and conventions by glee clubs organized on the spot." Percy spent some time learning performance with a local minstrel group, where he quickly picked up cakewalks and early ragtime tunes. There was also no shortage of either local or itinerant talent gracing the pianos around Joplin, and Wenrich took this all in as he often wandered through the downtown area which featured dozens of saloons and J. Frank Walker's Music Store. Percy also became known as "The Joplin Kid" during this time, a title he kept with him for many years. Just the same, for the 1900 enumeration he was shown working as a postal clerk under his father, music not yet established as a career.

The young Wenrich's first published work was written at age 17. It was L'Inconnu, which Percy described as "a two-step with a fancy title." He had a vanity pressing of one thousand copies printed by Sol Bloom Publishing in Chicago, and sold it one piece at a time back in Missouri and Kansas. It wasn't long before Percy found himself desiring a higher level of musical training, so he set off for the Chicago Musical College, run by none other than Florenz Ziegfeld Sr., father of the future Broadway entrepreneur. He also studied organ under Louis Falk. In six months, his money gone, he returned to Joplin. However, six months later in 1901 Wenrich relocated to the windy city to be closer to the major Midwest publishers.

While playing at the Congress Cafe and the Savoy, Percy got two popular styled pieces published by performer Frank Buck of Buck and Carney, including Just Because I'm From Missouri. He found his first career music job working with McKinley Music Company as a melody writer on demand. During that time he knocked off many numbers for McKinley, some possibly under unknown pseudonyms, for an average $5.00 each, and had some teaching pieces, such as The Katydid's Patrol for Ten Little Fingers, published as well. At times Percy commuted north on the train to Milwaukee, Wisconsin, where he demonstrated songs, and some were published there as well. He lived in Milwaukee for a while, working the music counter at Gimbel's Department Store. It was hard work, but Wenrich noted that it kept him from having to play in "the district" where the brothels were located, a move up from the life of many pianists at that time.

Back in Chicago, Percy met either Jerome H. Remick or, more likely, his manager Fred Belcher, and established loose ties with that publishing house. He would eventually have an enduring and fruitful relationship with the Remick company. During this time period he found his most popular works to be piano rags. While Wenrich's rags were not as refined or cohesive as those of classic composers or even some of the Tin Pan Alley writers, his gift for a memorable melody caused people to take notice. The first of them was Ashy Africa in 1903 which had been not just published but named by Buck before his move to McKinley. Then came Noodles, a much more authentic rag, but published by Arnett-Delonais instead of his own employer. The Smiler from 1907 became his best-selling rag without lyrics. It was subtitled "A Joplin Rag," which could have been interpreted as emulating the work of the more famous composer Scott Joplin, but Percy insisted that it referred to the style of piano played in his home town, which is the more sensible reference.

He would eventually have an enduring and fruitful relationship with the Remick company. During this time period he found his most popular works to be piano rags. While Wenrich's rags were not as refined or cohesive as those of classic composers or even some of the Tin Pan Alley writers, his gift for a memorable melody caused people to take notice. The first of them was Ashy Africa in 1903 which had been not just published but named by Buck before his move to McKinley. Then came Noodles, a much more authentic rag, but published by Arnett-Delonais instead of his own employer. The Smiler from 1907 became his best-selling rag without lyrics. It was subtitled "A Joplin Rag," which could have been interpreted as emulating the work of the more famous composer Scott Joplin, but Percy insisted that it referred to the style of piano played in his home town, which is the more sensible reference.

He would eventually have an enduring and fruitful relationship with the Remick company. During this time period he found his most popular works to be piano rags. While Wenrich's rags were not as refined or cohesive as those of classic composers or even some of the Tin Pan Alley writers, his gift for a memorable melody caused people to take notice. The first of them was Ashy Africa in 1903 which had been not just published but named by Buck before his move to McKinley. Then came Noodles, a much more authentic rag, but published by Arnett-Delonais instead of his own employer. The Smiler from 1907 became his best-selling rag without lyrics. It was subtitled "A Joplin Rag," which could have been interpreted as emulating the work of the more famous composer Scott Joplin, but Percy insisted that it referred to the style of piano played in his home town, which is the more sensible reference.

He would eventually have an enduring and fruitful relationship with the Remick company. During this time period he found his most popular works to be piano rags. While Wenrich's rags were not as refined or cohesive as those of classic composers or even some of the Tin Pan Alley writers, his gift for a memorable melody caused people to take notice. The first of them was Ashy Africa in 1903 which had been not just published but named by Buck before his move to McKinley. Then came Noodles, a much more authentic rag, but published by Arnett-Delonais instead of his own employer. The Smiler from 1907 became his best-selling rag without lyrics. It was subtitled "A Joplin Rag," which could have been interpreted as emulating the work of the more famous composer Scott Joplin, but Percy insisted that it referred to the style of piano played in his home town, which is the more sensible reference.Around 1905 Percy met the up and coming vaudeville performer Dolly Connolly (1888 to 1965). He was instantly enamored with here, and it wasn't long before they married on July 3, 1906. Being a musician he understood how important it was to use that gift, and she therefore was encouraged to continue her career with his support, something uncommon during this time period. Percy started collaborating with lyricists, and produced his first minor song hit, Rainbow, an Indian Intermezzo. When lyrics were added to transform it into Come Be My Rainbow, Percy had enough of a hit to prompt a change in locale. The couple then moved to New York in 1909, and his first six month check from Remick totaled around $4,200, a substantial amount.

His next big hit secured his place as a songwriter. The most credible form of the story (there are many variants) are as follows. A friend of Percy's, Stanley Murphy, had just returned from a stay in Europe. Wenrich met him at the dock and Stanley relayed the lyrics for a potential hit song that they immediately wanted set to music. Wenrich did not have a piano available, so went to the manager of Remick's on Broadway and talked the manager into using a piano for 30 minutes. At the end of that time he was not satisfied with the tune as a whole, and pleaded for another 30 minutes. The manager refused and a noisy exchange occurred.

According to Wenrich, Jerome Remick himself came over to see what the fuss was about, and conceded to let the songwriter have another 30 minutes at the piano. Once finished, the composer then rushed to demonstrate the newly minted song for Remick who was on his way out the door for a long weekend in Atlantic City. Remick was unimpressed with the sentiment of the lyrics, but took the song with him and said he would render a decision on Monday. However the tune kept bouncing around in his head for several days, and Remick finally relented calling Wenrich back in, and telling him (with instinctual ego intact), "You must have a hit here. I've never been able to carry a tune, but here's a song even I can sing! Any song that even I can't forget must become a hit." Remick was known to be relatively unmusical. However, he proceeded to prove his point by performing "Put on your old sun bonnet," but kept on singing "grey bonnet." Wenrich tried to correct the publisher, but he was waved aside, saying "Let it stay that way. It sounds better." So that was how Wenrich and Murphy's big hit was named. Put On Your Old Grey Bonnet was an instant success, and was widely performed for many years.

"You must have a hit here. I've never been able to carry a tune, but here's a song even I can sing! Any song that even I can't forget must become a hit." Remick was known to be relatively unmusical. However, he proceeded to prove his point by performing "Put on your old sun bonnet," but kept on singing "grey bonnet." Wenrich tried to correct the publisher, but he was waved aside, saying "Let it stay that way. It sounds better." So that was how Wenrich and Murphy's big hit was named. Put On Your Old Grey Bonnet was an instant success, and was widely performed for many years.

"You must have a hit here. I've never been able to carry a tune, but here's a song even I can sing! Any song that even I can't forget must become a hit." Remick was known to be relatively unmusical. However, he proceeded to prove his point by performing "Put on your old sun bonnet," but kept on singing "grey bonnet." Wenrich tried to correct the publisher, but he was waved aside, saying "Let it stay that way. It sounds better." So that was how Wenrich and Murphy's big hit was named. Put On Your Old Grey Bonnet was an instant success, and was widely performed for many years.

"You must have a hit here. I've never been able to carry a tune, but here's a song even I can sing! Any song that even I can't forget must become a hit." Remick was known to be relatively unmusical. However, he proceeded to prove his point by performing "Put on your old sun bonnet," but kept on singing "grey bonnet." Wenrich tried to correct the publisher, but he was waved aside, saying "Let it stay that way. It sounds better." So that was how Wenrich and Murphy's big hit was named. Put On Your Old Grey Bonnet was an instant success, and was widely performed for many years.This song was soon followed by the rousing That Alamo Rag. His next big hit, Red Rose Rag, was written for Connolly, and was also well received. In fact famed comedian George Burns mentions it as one of his early favorites in two of his books of reminiscences, and used it as a theme for many years. Wenrich followed this up with a male quartet favorite, Moonlight Bay. He recalled knocking it off in Atlantic City, New Jersey, while sitting at the Old Vienna Cafe, a meat market he had invested in around 1910: "It was a swell night, with the moon streaming over the ocean. Just as I ordered another beer I thought I heard some guy ask the orchestra to play a piece called 'Moonlight Bay.' I was mistaken; they hadn't requested it, for the reason there was no such song, but I got to thinking what a swell title it would make and went home to work it. I also made dough on that piece."

In 1913 Percy dabbled in publishing for a year, teaming up with businessman Homer Howard to form the Wenrich-Howard Publishing Company in the Shubert building at 1412 Broadway in New York. They put out a few of his pieces, including the hits Whipped Cream Rag and the Indian-themed song Snow Deer. However, the business end was too much for him to handle and gave him little time to write, so the company was dissolved in 1914 and Percy returned to writing and performing as much as possible with Dolly. His next stop as a contracted writer was at Leo Feist Publishing, who had purchased the Wenrich-Howard catalog. There he penned When You Wore a Tulip and I Wore a Big Red Rose, one of his biggest sellers. It didn't start out that way, however, as Wenrich thought it to be a flop. In its first six months the piece hardly moved, then it suddenly became highly popular, ultimately selling over two million copies.

Throughout the 1910s until the eventual demise of vaudeville in the late 1920s, Wenrich both wrote for and toured with Dolly, as well as accompanied her during her stint as a recording star with Columbia Records. He contributed to a few stage musicals during that time as well, collaborating with a number of talented lyricists, including Howard Johnson of M-O-T-H-E-R fame. His first effort consisted of three songs contributed to The Crinoline Girl which ran a respectable 96 performances in 1914, and starred popular female impersonator Julian Eltinge. Eltinge would also star in the short-lived Cousin Lucy in 1916, with a score shared by Percy with none other than Jerome Kern. In 1914 Wenrich became a charter member of ASCAP in New York.

A lesser known 1913 hit of Wenrich was highlighted in the Music Trade Review of April 24, 1915, explaining to some degree how fickle the public can be, and how one performance can make a difference:

The psychology of song popularity has long been the study of those who have to do with the publishing of the bulk of our music of to-day, the sort known as "popular," though it is not usually referred to in that particular way. The idea of finding out what the public wants and endeavoring to make a good guess at it is the real basis of the music publishing business to-day — the basis upon which sales totals are built, despite all the talk there may be regarding the "forcing of hits."

|

Some popular songs have sought success and won it. Others have won success through their intrinsic merit, not suddenly and overnight, as it were, but gradually, the sort of success that generally means a long and profitable life. One of the numbers to be included in this category is "When It's Moonlight in Mayo," the beautiful Irish ballad by Jack Mahoney and Percy Wenrich, two of the stars in the music game.

For considerably over a year "When It's Moonlight in Mayo" has been moving along quietly without being featured very strongly. Then one night Percy Wenrich, the composer, and his partner, Dolly Connolly, sang the number while appearing in vaudeville at the Majestic Theater in Chicago so effectively that several of the critics gave more favorable attention to that one song than they did to the balance of the show. From that time on "When It's Moonlight in Mayo" has enjoyed a high place among popular music in the West.

Before the Wenrich triumph, however, Van and Schenk, the popular pair of vaudeville artists, were singing the number while on their tour of the Keith houses in the Eastern cities, and winning encores at every performance. The greatest tribute to the value of "When It's Moonlight in Mayo" as a song, however, came recently when Fiske O'Hara ran across it accidentally and introduced it in his Irish comedy drama "Jack's Romance," which is proving one of the most successful vehicles in which Mr. O'Hara has ever appeared. The theatrical critics were quick to show their appreciation of the value of the new number in their reviews of "Jack's Romance," and a writer in the New York American went so far as to say:

"Fiske O'Hara, the popular romantic actor of the good-natured Irish go-lucky types, had plenty of songs in his new play, 'Jack's Romance.' But the other day he accidentally came across another called 'When It's Moonlight in Mayo.' And Fiske O'Hara an hour later was glad that he did hear it, for he had picked for himself the ballad hit of the season…

"It is an Irish love song as pure in its sentiment as the mountain dew, and as fetching in its appeal as the big limpid blue eyes of Erin's comely daughters. Like all successful ballads it combines great beauty of melody with simplicity of form. The tune haunts your ear like some witching folk song you've learned as a child, yet not suggesting any definite one, because it is purely original and not in the least an imitation…"

Dolly and Percy generally got good press and reviews wherever they performed. One example from the Toronto World of February 22, 1916, as part of a visiting show read: "Decided favorites in their offerings of new songs, written by Percy Wenrich, were Dolly Connolly and the composer himself. A number sung for the first time in Toronto, 'Sweet Cider [Time],' which is both catchy and musical, proved the 'hit' of the performance. Composer and singer had to respond to several recalls and an encore was insisted upon…"

On his 1918 draft record Wenrich lists his employer as Leo Feist and his profession as Vaudeville Entertainer, and Dolly C. Wenrich as his wife. The Wenrichs were found in Manhattan for the 1920 enumeration with Percy listed as a music composer and Dolly as a theatrical actress. However, his birth state was incorrectly shown as Iowa. The remaining demographics were correct.

The Wenrichs were found in Manhattan for the 1920 enumeration with Percy listed as a music composer and Dolly as a theatrical actress. However, his birth state was incorrectly shown as Iowa. The remaining demographics were correct.

The Wenrichs were found in Manhattan for the 1920 enumeration with Percy listed as a music composer and Dolly as a theatrical actress. However, his birth state was incorrectly shown as Iowa. The remaining demographics were correct.

The Wenrichs were found in Manhattan for the 1920 enumeration with Percy listed as a music composer and Dolly as a theatrical actress. However, his birth state was incorrectly shown as Iowa. The remaining demographics were correct.At some point in the early 1920s Percy and Dolly moved to The Lambs Club, part of the Chatwal Hotel on West 44th Street in Manhattan. The 1920s are the time when Wenrich became most active on Broadway. With Raymond Peck he created the musical Maid to Love in 1920, which opened in Atlantic City and toured around the country, but did not do at all well. They revamped the story while keeping most of the songs, and in 1921 introduced The Right Girl starring Dolly as a main character. It fared better when it reached Broadway, falling just two short of 100 performances. The musical was reviewed in the New York Times on March 16, the reviewer insisting that "Percy Wenrich's score as several high spots - 'Love's little Journey' was good for half a dozen encores last night, and there were several other numbers to set the feet tapping. Dolly Connolly, come from vaudeville, sang several of the best numbers vivaciously…"

Some Party from 1922 was more of a revue, and it closed in about two weeks. In 1925 Percy and Raymond came up with Castles in the Air which ran a good 160 performances on Broadway in mid-1926, but without Dolly in the cast. As noted in the Music Trade Review of December 5, 1925:

"Castles in the Air," a new musical comedy, opened at the Olympic Theatre, Chicago, late last month. If the audiences at the first few shows and the newspaper critics are any judges it will prove one of the greatest musical successes of years. Such captions as "Looks like another 'Nanette,'" and "the best operetta in years," followed by "looks like a substantial portion for its promoters," appeared in the dailies following the opening. The book is by Raymond W. Peck and the music is by Percy Wenrich. The Chicago Journal said that the music by Wenrich gives him a place beside the late lamented Victor Herbert when that composer was writing at the very top of his inspiration…

Percy and Dolly ventured to France in spring of 1927 after Castles in the Air closed, the only clear evidence of any European excursions they made. His output nearly ceased during this period. However, The Bells of St. Gabriel's became a minor sensation for singer and composer Ernest R. Ball during a 1927 West Coast tour. Wenrich's last apparent Broadway contribution was Who Cares in the summer of 1930. With the Great Depression settling in, it was apparent that few actually did care, and it closed after three weeks.

Early in the 1930s Percy and Dolly retired from performance, staying in New York City. In 1930 Wenrich was listed as a guest at a Broadway hotel and the expected profession of a composer of music. However, his age was shown as five years younger than his actual 45, and Dolly was not found in the same residence but at the Hotel Belvedere on E. 48th. This may have been either a separation or a temporary situation while he was engaged with Who Cares, as they co-wrote an unusual advertisement song that year in praise of a farm combine of all things. Titled Hail to the Gleaner Baldwin, it was published by the Gleaner company in Missouri.

Not much is available on the Wenrichs in the 1930s. They occasionally appeared on WEAF radio from 1930 to 1932 in New York with Percy playing and Dolly singing 15 to 30 minutes of usually older songs per appearance. They did make a couple of special dinner club events in New York that in 1934, after which Percy was reported to have retired from writing and performance in 1934 once they moved out west to Hollywood, California. There are some reports that Dolly was in failing mental health by that time, which may have prompted the decision to partially retire. There was also the currency of his writing, which he discussed in the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette on May 4, 1934:

About a year ago Irving Berlin told the writer [Douglas Gilbert] beer and repeal [of national prohibition] would bring back the old, singable melodies. His prediction proved unfounded. The Broadway melodeers still stay specialized, turning out trick tunes and orchestrated novelties…

This has been a jolt to old-timers like Percy Wenrich, who wrote "When You Wore a Tulip" and "Put On Your Old [Grey] Bonnet." Here are two songs as singable today as they were in the days of the sitting-room pi-anner with Mamie thumping an accompaniment while the neighborhood boys and girls gathered 'round.

"I admit," said Mr. Wenrich, expanding on the trend of popular tunes the other day at the Lambs [Club], "that writing for crack bands, good musicians and professional singers has improved our popular music technically. But I can't see any melodic improvement.

"Take such a fine tune as Jerome Kern's 'Smoke Gets in Your Eyes.' You can't even play it, let alone sing it. It modulates from three flats to five sharps. Similarly, the contemporary Mamies can't play Berlin's 'Heat Wave.' Its tricky rhythm is way beyond the average pianist's technique…"

A song of Percy's that made a lot of dough for him and yet is scarcely recalled today is the war tune, "Where Do We Go From Here?"

"Curious thing about that one," Percy recalled, "Feist called me over to his office one day. Says, 'Percy, all the war tunes the boys sang in the past were just rum-ti-tum gags having nothing to do with fighting. Take 'Hot Time in the Old Town,' which was the hit of the Spanish-American War. Go ahead and knock one out and beat the rest of 'em to it.'

"So I asked Howard Johnson to do me a lyric. The next day he brought down a verse and chorus. 'It's lousy, Percy,' he said, 'But you can use it for a dummy, and I'll give you something better later.' It was 'Where Do We Go From Here?' a screwy lyric if ever there was one about a Broadway cabby who sang the refrain to his fares: 'Oh, boy, oh, boy, where do we go from here?' We never changed a line of it."

But these times, with their jittery tunes and scherzo scores, it'd take a [pianist lik Walter] Gieseking to play and a [soprano like Lily] Pons to sing, have not been kind to Percy. He rates a permanent Class A at the American Society of Composers, Authors and Publishers which assures him an annual stipend even if his songs don't sell a copy. This pays his rent, lunches and bar bill at the Lambs.

Yet for one who has contributed a half-dozen hits to the Broadway library of song he ought to be doing much better. Percy is an optimist, though, believing that repeal eventually will awaken the old conviviality and with it the old songs. Says the cycle'll get around to simple melodies "that a guy can play and sing, and I'll be doing all right again."

Wenrich was involved for many years with Songwriters on Parade, one of the last gasps of vaudeville, which featured a number of veteran songwriters performing their own works. They toured from 1931 to 1940 on the old Loews and Keith circuits, and Wenrich was part of the act for at least a portion of the later 1930s, in spite of his declared retirement. For the 1940 enumeration, taken in Hollywood, California, where they had been based for several years, Percy showed no occupation, while Dolly was a professional singer on the stage and in radio. The couple is listed on his 1942 draft record as living once again at The Lambs Club in Manhattan, and with no employer. Dolly's mental and physical health eventually did deteriorate to the point where Wenrich had her committed to a sanatorium in 1947, as nursing homes were still uncommon. The few symptoms that were reported suggest that she may have had Alzheimer's disease. The 1950 census showed her as an inmate in the Central Islip mental hospital in Suffolk County, New York. For that same census, Percy was living in New York City just two blocks south of Central Park near Carnegie Hall, and showed no occupation. Dolly was eventually released to the care of her sister after Wenrich's death.

"Ragtime Bob" Darch visited the elderly Wenrich in 1951 around the time of the release of the Doris Day film, On Moonlight Bay, of which the only featured song of his was the title. He was infirmed and unable to travel to his home town of Joplin for the premiere and a tribute, but was pleased by all the attention, sending along a telegram of thanks to all involved. Darch vividly remembers how touched Wenrich was by all of this, particularly when he heard a band that had been arranged for to play some of his songs for Percy outside of his apartment window.

In the late 1940s the retired composer resided in an apartment at the Park Sheraton Hotel in Manhattan. Percy Wenrich died peacefully in March 1952 after having lived a fulfilling and productive life. His body was laid to rest at Fairview Cemetery in his beloved Joplin, Missouri. Wenrich left behind an unforgettable legacy of happy memories through his music. Dolly survived her late husband, living off his ASCAP pension with her sister until 1965 when she passed on in New York. She similarly left us with a legacy of authentic recorded ragtime songs and happy memories.