|

Anotonio (Tony) Junius Jackson (October 25, 1882 to April 20, 1921) | |

Compositions Compositions | |

|

c.1902-1906

Michigan Water Blues †The Naked Dance † 1904

The Clock of Time [1] †1914

We've Got Him1915

You're Such a Pretty Thing †1916

Miss Samantha Johnson's Wedding DayWaiting at the Old Church Door Pretty Baby [2,3] I've Got 'Em!: There Ain't Nothin' To That [4] 1917

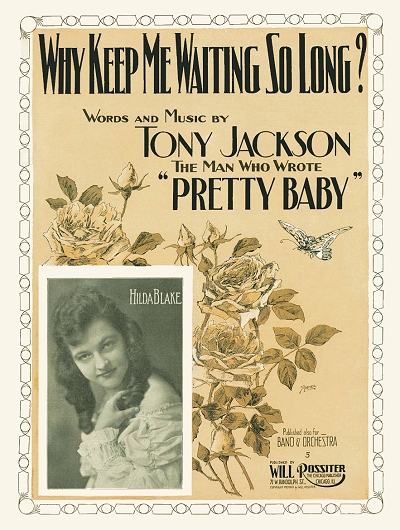

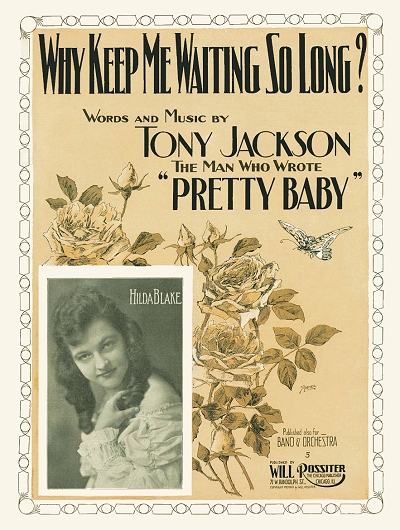

Why Keep Me Waiting So Long?(Don't Leave Me in the) Ice and Snow I've Been Fiddle-ing [2,3] Some Sweet Day [5,6] Sympathizing Moon † Pick-It Boy † When Your Troubles Will Be Just Like Mine † |

1918

Take Me Into Your Heart [7]1921

I'm Cert'n'y Gonna See 'Bout ThatUnknown/Uncertain

Bridal Moon †Honey Babe, My Heart Cries Out for You † Jackson Glide † Little Baby Mine † Our Hearts are Sad † Partial Moon † Pretty Dear † Secrets of Flowers †

1. w/Glover Compton

2. w/Gus Kahn 3. w/Egbert Van Alstyne 4. w/Jack Frost 5. w/Ed Rose 6. w/Abe Olman 7. w/Bill Haskins † Unpublished or Lost †† Listed in the book "Oh, Mr. Jelly" |

Among the legendary performers of New Orleans or Chicago ragtime, the name of Tony Jackson usually rises to the top when the discussion turns to piano players - even above his highly self-esteemed colleague Ferdinand "Jelly Roll" Morton. Morton himself claimed that he learned much about performance from Jackson, and held him always in the highest regard, even almost two decades after Jackson's premature death. Some today see him as an early icon amongst prominent black LGBTQIA+ performers. But as with many legends, there are some mysteries left behind, and many untold stories as well. Some of the mysteries or misconceptions will be challenged here, but even at that, some of the more salacious or curious stories will have to remain untold.

The first mystery goes to a topic that was a wider variable among ragtime musicians who were primarily performers than it was among those who were primarily composers. That is the issue of age accuracy at any given point in their life. A number of noted pianists tended to stretch reports of their longevity, or aged in reverse from year to year at times. In the case of the Jackson family, the entire lot appears to have inherited the rare gene that allowed them to grow older at a much slower rate than most ordinary people. Therefore the dates reported here are mostly derived from the earliest possible census records in each case, providing a higher level of probable accuracy than the later ones.

Antony (or Antonio) Jackson Sr. was born in South Carolina in March of 1843 into slavery. He was a fisherman for many years, but after the Civil War moved to Louisiana where he was listed as a laborer, potentially still fishing for a living. It was there he met and married Rachel Dennis, sometimes thought to have been born in Virginia. However, her records back to 1860 indicate her to be a Louisiana native born around 1849. The pair are listed as Toney and Rachael in the 1870 enumeration, their race shown as mulatto. Subsequent census records showed the family as black. Starting around 1870 the couple routinely added to the family. First along was Andrew in June 1870, then Sarah around 1872, Maria (or Mariah) around 1874, Ida in June 1876, and Louvina in October 1878. As of 1880, Toney (as he appeared through the 1910 enumeration) had not yet been born, discounting the misquoted 1876 date that his sister Ida stated in an interview, which was actually the year of her own birth. (Note that in 1910 Ida was already stated as six years younger than her true age, as was Louvina, and that Marie states that she only aged one year between 1910 and 1920, showing as 35 and 36 respectively. Ida had subtracted a full decade from her actual age in 1920.)

|

The correct year of birth for Antonio Junius Jackson Jr. was 1882, which is consistent at least with the very definitive 1900 census, the only one which showed a month and year of birth. The 1910 enumeration showed a potential 1885 date, and his 1918 draft card an 1884 date. He was certainly not born in 1888 as the 1920 census would indicate. This would have meant that he was playing in brothels by the age of 9 or 10, which even in New Orleans was somewhat of a stretch. The best confirmation of his birth year is that he was born a twin. His brother, Prince Albert Jackson, died in New Orleans on January 5th, 1884, and according to his official death certificate was fourteen months old, again establishing 1882 as Toney's actual year of birth.

Toney and Prince Albert were evidently the last children born to Antonio and Rachel. It is unclear if he was born as Antony or Antonio, but he and his family spelled the name as Toney through most or all of his stay in New Orleans up through 1912, and even some advertisements in New Orleans used the same spelling. It appears he started using the more traditional Tony once he moved to Chicago around 1914. This biography will use Tony from this point for better continuity.

Jackson was born in uptown New Orleans, a town known to be the home of some of the most famous brothels and least effective law enforcement in the entire South. Living originally on First Street between Annunciation and Rousseau, then Amelia Street near Tchopitoulas, and by 1900 on Magazine Street near the edge of the Treme and the French Quarter, the family was located in the area where at least some of the prostitution was centered in the 1880s and 1890s. Tony and his siblings were certainly aware of it, as many children were introduced to brothels and bars at a young age through earning money doing deliveries of documents or contraband. The problem was so rampant and seemingly unenforceable that in 1897 New Orleans Alderman Sidney Story, who was opposed to the vice, but who recognized that it had to be controlled somehow, came up with an ordinance that set aside a district outside of which prostitution and vagrancy, or the residency of "abandoned or sinful women" was made illegal. Given that it did not specifically legalize prostitution or drug use, etc., inside the noted boundaries of the district, it actually was upheld as Constitutional when challenged, thus creating the only area in the United States were such behaviors were more or less allowed. Much to the chagrin of the otherwise staid and churchgoing Mr. Story, those outside of New Orleans named "The District" Storyville after his legislation. Jackson was there for much of the existence of the District (1898 to 1917), which after it was shut down left no clear home for "legal" prostitution until Nevada voted to allow it decades later.

Tony was said to have been a lonely child, but also one with a great desire to make music. His sisters kept a close watch on him and tried to keep him from going into the rougher areas of their neighborhood. As it was, he was rarely allowed outside of his small yard. However, he evidently had some exposure to pianos or some keyboard instrument, and tunable instruments like banjos as well. Reportedly at the age of seven (although this may be at slight variance to fact), he managed to piece together the guts of a piano or similar keyboard instrument with some sort of tunable string system, creating a giant harpsichord of sorts. On this he gave concerts of the music he knew, which was church music and hymns for the most part. His first full performance was allegedly of How Sweet To Have a Home in Heaven.

The lad's contraption was obviously not good enough to render any serious music education, so within a short time an arrangement was worked out with a neighbor exchanging dishwashing duties for time on the neighbor's old reed organ. Even this had limitations, but Tony had little choice at that time. By age thirteen he was finally allowed regular contact with an actual piano. Through the efforts of the corner barber and orchestra leader Adam Olivier, Jackson was allowed to use the piano in the saloon next door to the barber shop in the mornings before daily business commenced.

Tony obviously had been well-prepared after six or so years of warm-up to dig right in and learn all he could about upright pianos. Before long he was asked to play in the saloon at various times, and by age fifteen he was reportedly considered to be among the best pianists in that part of New Orleans. Among his first semi-regular gigs was playing with Olivier's band, which included Bunk Johnson at that time. The next obvious step was to move northwest into the Treme and the District, playing at saloons and brothels.

This transition was evidently easy, and his role there uncontested, as many testimonials after the fact will assert. By the time of the 1900 census at age eighteen, Tony Jackson ruled the roost in Storyville,

|

Now performing routinely in the brothels of Basin Street and the District, Jackson was often heard at the great white upright piano in the ostentatious and overdone parlour of Madame Willie V. Piazza and her octoroons at 317 North Basin Street. He was also a favorite of Antonia Gonzales, around the corner on Canal Street, who had more than one obvious talent. She would often break out her cornet and play along rather proficiently with Jackson during slow periods or parties. Another frequent haunt was that of Gipsy Shafer (or variations including Shaffer and Schaeffer) at the corner of Iberville and Villere streets. Concerning his work there, Ferdinand "Jelly Roll" Morton later recounted his memories of Jackson to historian Alan Lomax in 1938:

Tony Jackson played at Gypsy Schaeffer's, one of the most notoriety women I have ever seen in a high-class way. She was the notoriety kind that everybody liked. She didn't mind spending her money, and her main drink was champagne, and, if you couldn't buy it, she'd buy it for you in abundance. Walk into Gypsy Schaeffer's and, right away, the bell would ring upstairs and all the girls would walk into the parlor, dressed in their fine evening gowns and ask the customer if he would care to drink wine. They would call for the "professor" and while champagne was being served all around, Tony would play a couple of numbers.

If a naked dance was desired, Tony would dig up one of his fast speed tunes and one of the girls would dance on a little narrow stage, completely nude. Yes, they danced absolutely stripped, but in New Orleans the naked dance was a real art.

Following this narrative Morton played his own recollection of Jackson's Naked Dance which has since become a favorite of many ragtime and stride pianists. How authentic the novelty piano-styled Morton recording is in relation to Jackson's original is anybody's guess. At the very least he captured the essence of Tony's flashy style.

The pianists of Storyville knew that they could often convince the "clients" of a parlor that their playing had something to do with the client's success. They also knew that those fresh off the train at the Basin Street station who had been lured in by schillers handing out cards on the street would also want to show off their generous nature in order to impress the girls, so they would often tip the pianists excessively. Making $100 or more in a night was hardly unheard of in any of the brothels. What was surprisingly hard to find, however, was a white pianist. One named "Kid Ross" was the exception, not the rule, as Jackson, Morton, and many of their Creole or Negro colleagues were most highly regarded in the district.

While they weren't playing the brothels, or taking advantage of the free services offered to them there, performers like Jackson also played in some the saloons along Bienville or St. Louis streets. Frank Early's My Place saloon at the corner of Franklin and Bienville was where Jackson often held court, singing songs like "I've got Elgin movements in my hips with twenty year's guarantee." As he lived above the saloon for a while, it was supposedly here that he wrote the piece Pretty Baby (a notion that remains unconfirmed), which would not gain much notoriety until he moved to Chicago years later. Jackson was said to have fitted dozens of different lyrics to the tune, most of them bawdy, and usually tailored to the joint he was in and the present company. Morton, again through Lomax, recalled those times as well as if setting a scene in a dime novel:

Those days I hung out at Eloise Blankenstein and Louis Aberdeen's place [actually Abadie's Café which was often mispronounced as Aberdeen's] - the rendezvous for all the big sports like Pensacola Kid, who later came to be the champion pool shooter of the world. Bob Rowe, the man who didn't know how many suits he had, and his wife, Reday Money, were regulars, also the Suicide Queen, who used to take poison all the time. Tony Jackson also hung out there and was the cause of me not playing much piano.

The favorite of most pianists, gamblers and millionaires was The Frenchman's Saloon at the corner of Bienville and Villere streets. Morton recalled that this was the place to hang out at 4:00 AM after most of the night's activity was over, and that there was virtually no discrimination there. Indeed, until legislation was passed in the 1890s distinguishing Creoles from Creoles of Color, they were often regarded as equals. While now considered legally to be Negros, even with 1/8 black blood, in Storyville they were considered to be just people, especially the ones who provided entertainment. Jackson was more black than Morton, but he was usually treated with the same respect. Even Morton, who was very reluctant to say too much about the talents of many other musicians, was very forthcoming with his obvious praise and respect for Jackson, even if a bit exaggerated over time:

All these men [the pianists who frequented late nights at the Frenchman's Café] were hard to beat, but when Tony Jackson walked in, any one of them would get up from the piano stool. If he didn't, somebody was liable to say, "Get up from that piano. You hurting its feelings. Let Tony play." Tony was real dark, and not a bit good-looking, but he had a beautiful disposition. He was the outstanding favorite of New Orleans, and I have never known any pianists to come from any section of the world that could leave New Orleans victorious...

There was no tune that come up from any opera or any show of any kind or anything that was wrote on paper that Tony couldn't play. He had such a beautiful voice and a marvelous range. His voice on an opera tune was exactly as an opera singer. His range on a blues would be just exactly like a blues singer...

Tony happened to be one of those gentlemens that a lot of people call them a lady or sissy... and that was the cause of him going to Chicago about 1906 [actually 1912]. He liked the freedom there... Tony was the favorite of all who knew him, but the poor fellow drank himself to death.

As Morton succinctly pointed out, Jackson was indeed known to be homosexual. He also suffered from epilepsy. A hard life mixed in with those other factors may have also spurred on alcoholic tendencies acquired while in his teens. They did not, however, affect his overall popularity, and certainly the madames and their girls felt quite comfortable with Tony. However, there were some, even in Storyville, who were less than tolerant or understanding about what they considered to be an aberrant behavior or lifestyle, so he had to keep some facets of his life under wraps while living in the South.

There were a number of other similar remembrances of Tony's talent recounted by musicians to author Nat Shapiro for his book Hear Me Talkin' To Ya published in 1966. Among them, the great composer Clarence Williams who said "at that time everybody followed the great Tony Jackson. We all copied him. He was so original and a great instrumentalist. I know I copied Tony... About Tony, you know he was an effeminate man - you know... He was of a brown complexion, with very thick lips." Another admirer was trumpeter Bunk Johnson who said that "Tony was dicty," a term often applied to well-dressed gentlemen of color. Clarinetist George Baguet further recalled: "He'd start playin' a Cakewalk, then he'd kick over the piano stool and dance a Cakewalk - and never stop playin' the piano - and playin', man! Nobody played like him!"

Singers loved him as well. In Hear Me Talkin' To Ya blues pioneer Alberta Hunter had only fond memories of him:

Everybody would go to hear Tony Jackson after hours. Tony was just marvelous - a fine musician, spectacular, but still soft. He could write a song in two minutes and was one of the greatest accompanist I've every listened to... He had mixed hair and always had a drink on the piano - always!... Yes, Tony Jackson was a prince of a fellow, and he would always pack them in. There would be so many people around the piano trying to learn his style that sometimes he could hardly move his hands - and he never played any song the same way twice.

Jackson's philosophy was fairly simple. In order to be successful a pianist should be able to try and please every customer. This means learning every style and every melody, including the latest popular tunes, opera airs, coon songs, rags, and all the blues imaginable. His ability to sing as well put him over the top in this regard. As quoted or paraphrased in Storyville by Al Rose, he believed, "What's the man gonna think he comes in here slaps a twenty on the box and says 'Poets and Peasants Overture' I got to tell him I can't play it? Hell, I learn all them things, mister. All of 'em!"

Writer and amateur pianist Roy Carew, who was a year younger than Jackson, was transported from his native Michigan to Gulfport, Mississippi in 1904, and ended up pursuing a job as a bookkeeper in nearby New Orleans. It did not take him long to discover the enchanting sounds of Jackson, and as a result became a life-long admirer and sometimes documentarian of not only Jackson but "Jelly Roll" Morton. He recalled his time in New Orleans from nearly four decades earlier in an article published in the Record Changer magazine in February 1943:

In the early days of the present century, there stood, at the downtown corner of Villere and Iberville Streets, in that part of New Orleans known as Storyville, a frame dwelling of the type descriptively called "Camel-Back." This name was applied to houses which had a single story in front but were two stories in back. The house rested on a brick foundation a few feet high, and four or five wooden steps led up to the front door which faced on Iberville Street. On the glass portion of the door was painted the inscription, "Gonzales, FEMALE CORNETIST." There was no yard in front, nor at the side, and the brick banquettes [porches or raised sidewalks] extended right up the side of the house, but a few passengers got on or off in that neighborhood; the dance halls and flashy places were two or three blocks toward the river, nearer Basin Street.

One evening during the winter of 1904-1905, I was strolling aimlessly about downtown New Orleans, and in the course of time I found myself approaching the corner I have described. As I neared the front of the [Antonia] Gonzales establishment. I could hear the sound of piano playing with someone singing, which my ears told me was coming from the Villere side of the house. Always found of popular music; I immediately walked to the side of the house and got as close to the music as possible with the banquette going right up to the side of the house. I found myself standing under one of the windows of what probably was Madam Gonzales' parlor, listening to the "professor" playing and singing. That night was thirty-eight years past now, but it is almost as clear in my memory as if it were last night. It was the most remarkable playing and singing I had ever heard the songs were just some of the popular songs of that day and time, but the beat of the bass and the embellished treble of the piano told me that here was something new to me in playing. And the singing was just as distinctive. It was a man’s voice that had at times a sort of wild earnestness to it. High notes, low notes, fast or slow, the singer executed them all perfectly, blending them into the perfect performance with the remarkable piano style. As I stood there, I noticed another listener standing on the edge of the sidewalk a little ways away. I did not know who he was, but afterwards found out that he was another local piano player, Kid Ross. I think. I never got to know the man, but I will never forget our short conversation.

"Who in the world is that?" I asked, indicating the unseen player as I steeped over to him. "Tony Jackson," he replied. "He knows a thousand songs."

|

Roy ended up being one of the few white enthusiasts that got to know Tony fairly well, and was turned on to many popular tunes, buying the music for them once he heard Tony play them. He was also responsible for Morton's recreation of Jackson's Naked Dance during the 1938 recording sessions supervised by Lomax. Roy and others also insisted that Jackson wrote many more tunes than he was ultimately credited with, often selling them outright to other composers for five to ten dollars, then not contesting when they took credit. Morton suggested that the general population of the 1940s actually knew some of these purloined tunes. One of these alleged songs actually lived a long life, giving birth to the name of a genre.

After having been confined to his back yard in his early years, then to New Orleans and District through his teens, it is no wonder that Tony developed some wanderlust. So when he was offered an opportunity to hit the road in 1904 he readily accepted. In the summer of 1904, he made what was probably the only tour of the vaudeville theatres in his career. Tony was engaged as a featured entertainer with the Whitman Sisters’ New Orleans Troubadours, in a troupe that included fellow Storyville pianist Albert Carroll, who was acting as the musical director. It didn't take long for Jackson to tire of the constant travel required in vaudeville, and having become a bit disgruntled he left the troupe when they reached Louisville, Kentucky.

It was there that Jackson met local performer Glover Compton and the acknowledged top player in Louisville, "Piano" Price Davis. Davis was already earning a reputation as a gambler and an unreliable performer in spite of his talent, so Compton was rising in stature while taking over many of Davis' gigs when he was a no-show. While much of this part of the story is based on Compton's memories as related to writer Rudi Blesh in 1949, most of it has turned out to be fairly accurate, so it is plausible. Jackson was evidently a bit tired of being on the road and was hankering to get back to New Orleans. Compton and Jackson soon became friends, performing for a time at the Cosmopolitan Club. They also wrote a song together, which remains unpublished, but Compton recorded it in his later years. That piece, The Clock of Time, was reportedly repurposed in 1922 by composer J. Berni Barbour as the salacious My Daddy Rocks Me (With One Steady Roll), the song which ultimately provided the name for the genre of Rock and Roll.

The question would remain as to how Barbour got hold of that piece, which given Compton's scant compositional history was most likely driven by Jackson. A Kentucky native, Barbour was in Chicago by the late 1890s for schooling, and in 1903 co-founded with Nathaniel Clark Smith what is considered to be the first Black-owned and operated music publisher in America. He was certainly in Chicago when Compton ventured up there in 1906, followed shortly by Jackson over the next couple of years. So there were many opportunities for Barbour to have heard the piece, and perhaps even purchased it from Jackson. In any case, it provides another relatively direct tie between ragtime and its distant offspring rock and roll.

After earning enough for his return trip, Jackson retreated back to New Orleans for a while. He once again reigned over Storyville and was sought out by virtually every musician who came into town. It is very plausible that those from St. Louis, New York or Chicago continually suggested how well he would do in any of those cities, but Tony was comfortable being the musical ruler of his Creole kingdom, and resisted for some time. His favorite haunt during these years was Frank Early's Café.

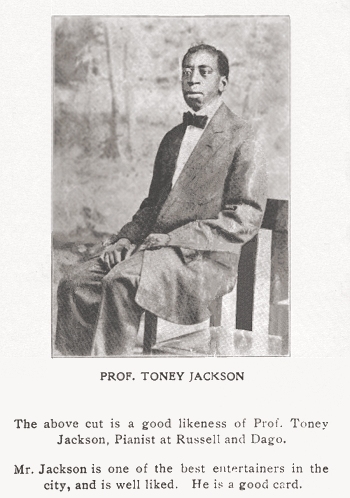

The exact time line is uncertain, but Jackson evidently divided his time between Chicago and New Orleans from around 1905 to 1909. In 1905, Tony reportedly made his first trip to Chicago with fellow pianist Bob Caldwell, whose playing paled in comparison to Jackson's. He made yet another trip to Chicago during the winter of 1907-1908, playing at [Bob] Russell and [Sidney] Dago’s Café on the Southside. Compton remembers seeing him in town a couple of times during his sporadic travels between Louisville and Chicago, but with no definitive dates. Roy Carew, on the other hand, distinctly remembers visiting Jackson in Chicago while he was on his way to family visit to Michigan in early 1909.

By the time of the 1910 census Tony was back in New Orleans living with his parents and sisters at 3928 Laurel, listed as a musician. He was also playing at spots outside of the District, and expanding his fan base. Exactly when he permanently moved to Chicago for certain is unclear. There are many reports that it was around 1912. If he did move then, Tony returned to New Orleans in 1913 upon the death of his mother. His absence in Chicago directories, presence in New Orleans papers, and a 1914 song publication suggests a more probable year of a northward migration as late 1913 or 1914 for the legendary pianist.

Once in Chicago Jackson realized some freedoms that he did not have in the South. While it is not known if medical care there was much better in terms of treatment for his epilepsy, it was easier for him to be openly gay among his circle of musical friends without ridicule or scorn. Tony worked in a variety of establishments, including some associated with brothels. However, he was also more accessible in a sense for the general public to come and hear him perform in more traditional venues, which they did. Before long Tony hooked up once again with Glover Compton. They worked as a dual piano act from time to time over the next several years. According to Glover, he and Jackson exchanged many ideas as well, expanding the scope of how each of them played, although this point may be merely academic. Another occasional playing partner and friend was Shelton Brooks who was becoming known as a notable composer as well.

Jackson's first gigs in Chicago were most frequently on State Street at Teenan Jones’ Elite No. 1 and Elite No. 2. His sister, Ida, and brother-in-law and second oldest sister, David and Maria Sutton, moved up to Chicago from New Orleans around 1915, and they moved in with Tony in his apartment at 4111 South Wabash Avenue where all of them lived for the brief remainder of his life. He also returned from time to time to Russell and Dago's place, as advertised on the card reproduced above. Around 1916 Jackson was heard playing in the Pekin Café, which had long been associated with Chicago composer and performer Joe Jordan, who he also became friends with. He spent much of his last few years there and at the DeLuxe as an occasional resident pianist.

Original composition was an area in which Jackson was not lacking, but in which he did not have the same opportunity to exploit in print in New Orleans as he now did in Chicago. Compton recalled one 1915 number titled You're Such a Pretty Thing written for Glover's wife, Nettie Lewis. While it was not published it did become known by a few in Chicago. Compton recorded it during an interview in Chicago in 1956. But there was that one song of Tony's that kept making the rounds, and for which he was becoming increasingly famous. How it immortalized him is yet another fortuitous if contentious part of his story.

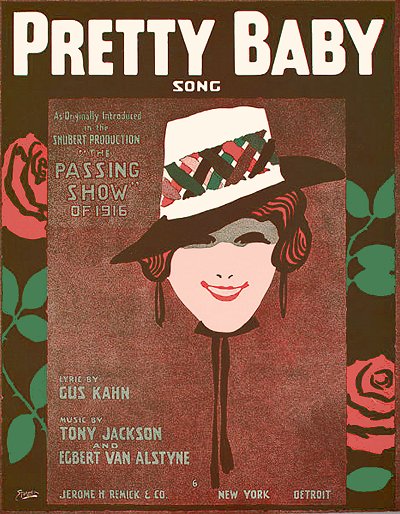

As of 1915, composer Egbert Van Alstyne and lyricist Gustave "Gus" Kahn were writing partners, and Van Alstyne was well known for a number of hits dating back to the turn of the century. Egbert was promoted to the position of Chicago manager of the publishing giant, Jerome H. Remick & Company. Among the team's duties for Remick was to scout out new songwriting talent, or at least procure good tunes. The tune they discovered Jackson performing became one of the most unnecessarily controversial subjects of Van Alstyne's life, largely because of misunderstandings on multiple levels, most of which have now been cleared up thanks to the efforts of diligent Van Alstyne historian, Tracy Doyle.

As it turns out, the two heard Tony Jackson performing his ditty Pretty Baby during one of their evening scouting missions in 1916, most likely to the Pekin or the DeLuxe. The melody was very charming and instantly attractive to Bert and Gus. However, since the current incarnation of the lyrics were written for Jackson's boyfriend, it obviously needed some major modifications to the text in order to be palatable for the Remick catalog. According to Morton in his LoC recordings, the supposed lyrics for the chorus ending went:

You can talk about your jelly rolls, but none of them compare,

With my baby, pretty baby of mine, pretty baby of mine.

The Jelly Roll reference, which Morton was not shy about using for his own professional name, generally referred to male genitalia. So once a deal was struck, Kahn necessarily set to work on cleaning up the piece a bit, and Van Alstyne added a verse that was adapted from a previous song he had composed that had fallen flat. As a result, the original edition offended Jackson supporters since it gave both Kahn and Van Alstyne co-composer credit, which was just the same quite appropriate, given their considerable input into the song. This regrettable miscasting of the situation actually made some musicians hostile to Van Alstyne for most of the rest of his life, something he found to be hurtful. Never mind that subsequent stage performances of the piece made it a big hit for all of the composers, and for Ziegfeld Follies star Fanny Brice, or that Jackson's name appeared above Van Alstyne's on the cover. And while many say that both the composer and his lyrics were compromised, it would be evident now that some of the original lines would have been unsuitable for mass publication. It is clear, however, that Jackson may not have got his share of royalties, having been paid $250 outright for the rights to the tune. In any case, Van Alstyne's daughter stated that this misunderstanding haunted him until his death in 1951.

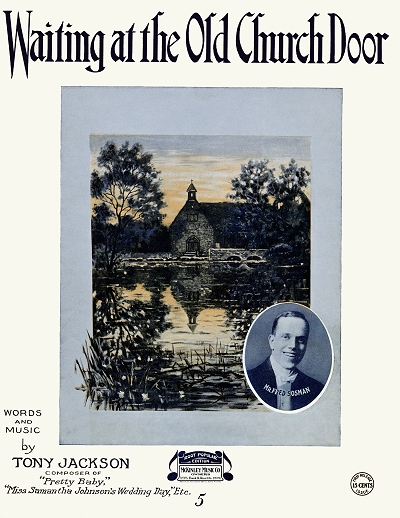

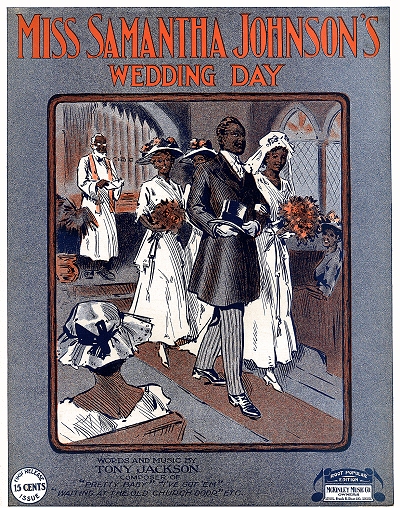

This song led to nine others that would be published or recorded by other artists over the next five or more years. Among the standouts are Miss Samantha's Wedding Day, Waiting at the Old Church Door, and Some Sweet Day composed with Abe Olman and Ed Rose. Additional songs have been mentioned in various sources, but no manuscripts have surfaced for them. Jackson never made much from his composition sales, but he continued to gain increased notoriety in Chicago and beyond. There was potential for even more, but for the time being he was reportedly satisfied with being a lounge pianist - the best in Chicago.

On this point Morton was quite clear in his interviews with Lomax. He claimed to have finally won a playing contest over Jackson, but the exact year or location is unclear, with "Jelly Roll" seeming to imply it was in Chicago. Morton was not, however, convinced he should have won. "I won a contest over Tony Jackson. That threw me in first line. I never believed that the contest was given to the right party, even though I was the winner. I always thought Tony Jackson should have had, I’m saying, the emblem as, as, the winner." As of the fall of 1918 Tony was living with his sister, Maria, and her husband, now at 4045 S. State Street, first flat in the rear. On his draft record filled out on September 12, he listed himself working as a pianist at the Pekin Theatre at 2700 State Street, and noted that he had weak eyes.

As of the fall of 1918 Tony was living with his sister, Maria, and her husband, now at 4045 S. State Street, first flat in the rear. On his draft record filled out on September 12, he listed himself working as a pianist at the Pekin Theatre at 2700 State Street, and noted that he had weak eyes.

As of the fall of 1918 Tony was living with his sister, Maria, and her husband, now at 4045 S. State Street, first flat in the rear. On his draft record filled out on September 12, he listed himself working as a pianist at the Pekin Theatre at 2700 State Street, and noted that he had weak eyes.

As of the fall of 1918 Tony was living with his sister, Maria, and her husband, now at 4045 S. State Street, first flat in the rear. On his draft record filled out on September 12, he listed himself working as a pianist at the Pekin Theatre at 2700 State Street, and noted that he had weak eyes.Ada "Bricktop" Smith had been part of the Panama Trio in 1916, along with singers Cora Green and Florence Mills. The group broke up in 1917, but was re-formed in 1918 with Carolyn Williams in place of Bricktop. Smith would later reign over the black American nightclub scene in Paris in the 1920s. For one special engagement in 1918 the trio hired Tony to help them launch a tour of Canada and the West. So for a short while he was a member of the Panama Four. Tony declined to go on tour with them, however, perhaps remembering life on the road during his vaudeville days in 1904.

Staying behind in Chicago he became acquainted with Joseph "King" Oliver and his band, but whether he sat in with that group is difficult to ascertain. In his one big brush with the law, Tony was arrested in August 1919 in connection with recent murders in the South Side, but was soon found to be innocent with a proper alibi, and quickly released. As of the January 1920 census Tony was shown as the head of his household, and was listed as a musician working in (rough translation from the handwriting) a cabaret. Living with him was his sister Ida working as a house cleaner, sister Maria and her husband David Sutton working in the stock yards, and the Sutton's three children, Eloise, William and Rachel.

Old habits die hard, and one that he cultivated in his teens caused him to die hard as well. Jackson, by the sum of many accounts, was an unapologetic alcoholic. He carried this trait with him from New Orleans to Chicago, and playing six to eight hours each night meant drinking eight to twelve hours each night, simply due to the nature of the work environment. The onset of prohibition in 1920 likely did little to slake his thirst for booze, and if it was available anywhere during the 1920s it was in Chicago. The quality and controlled potency of some of the alcohol during the beginning of prohibition after the stockpiles were used up has been called into question. Morton insisted that Jackson did not use "any dope" or narcotics of any kind.

No matter the situation, the damage to Jackson's liver had been done years before. There was also the onset of other maladies, of which syphilis has been suggested, but many of these symptoms may have been exacerbated by his epileptic issues. The onset of physical problems started to affect his voice, and then his finger dexterity, resulting in a marked decrease in his performance skills by early 1921. Jackson was terribly afflicted by March, suffering from extreme cirrhosis of the liver which had been progressing for years. He finally succumbed to these in April, not yet 39 years old.

A notice of his funeral was found in the Black-published Chicago Defender of April 30th:

Funeral services for Tony Jackson, popular songwriter and pianist, who died last week, were held in the chapel of the Jackson Undertaking Parlors, 29th and State streets, on Saturday. Funeral services were conducted by Rev. H. E. Stewart, pastor of Quinn Chapel Church. Miss Lizzie Hart Dorsey sang “The Rosary.” Prominent among those present at the services were Lovey Joe [Joe Jordan], Lilly Smith, Teenan Jones, Clarence Williams, Glover Crump [probably Compton], Tom Lemonier and the members of the New Orleans Jazz Orchestra. Interment was made in Oakwoods Cemetery.

Nearly a century later, Pretty Baby remains as Tony Jackson's most popular and sung tune - that we know of at least. No matter the origin of the piece, good music is good music, and virtually nobody ever said anything about the inimitable Tony Jackson that did not also utter those words - "good music."

Before commencing with other research on Jackson, the life of which snippets or variably sized synopses appear in a number of sources concerning Morton, the author gathered as much as possible from public and government records, information gathered from papers and libraries during a post-Katrina trip to New Orleans, similar information gathered from a Chicago trip, and Carew's fine articles in The Record Changer. After the outline was completed the gaps were filled in from a few sources, including Morton's sometimes questionable but still valuable remembrances (1938), Al Rose's fine book Storyville, New Orleans (1973), Nat Shapiro's engaging book Hear Me Talkin' To Ya (1966), and the handwritten notes and text by Rudi Blesh for and in They All Played Ragtime (1950-1971), which included long interviews with Glover Compton.

While this is a fairly complete look at Jackson's life, it should be noted that some important items may have been missed or misquoted, which would obviously be unintentional. Verifiable corrections would be most welcome and attributed as appropriate. There was also a conscious effort made to cast no aspersions whatsoever on Jackson's sexual preference or his epilepsy, as the author tends to feel fully enlightened on both of these issues as do his associates.