William Christopher Handy (November 16, 1873 - March 28, 1958) | |

Compositions Compositions | |

|

1907

In the Cotton Fields of Dixie [1]1909

Mr. Crump1912

Memphis Blues1913

The Jogo BluesPattona Rag The Girl You Never Have Met [1] Memphis Blues: Song [2] 1914

The Saint Louis BluesThe Yellow Dog [Rag] Blues 1915

Joe Turner BluesHail to the Spirit of Freedom: March The Hesitating Blues Shoeboot's Serenade 1916

Aframerican HymnBeale Street [Blues] In the Land Where Cotton is King [1] Ole Miss Rag [3] 1917

Thinking of Thee [1]The Hooking Cow Blues [4] 1918

Keep the Love Ties Binding [5]Ole Miss: Song [6] The Kaiser's Got The Blues [7] No Name Waltz [8] Roll Them Bullets Down [9] 1919

Though We're Miles Apart [6,8]1920

Aunt Hagar's Children [Blues]The Rough Rocky Road I'm Most Done Travellin' Long Gone (from Bowling Green) [10] 1921

Loveless Love: Blues NoveltyThe Bugle Blues [10] Aunt Hagar's Blues: Song [11] 1922

John Henry BluesApe Mister Eddie Sounding Brass and Tinkling Cymbals Harlem Blues South Side 1923

Sundown BluesAtlanta Blues Darktown Reveille [10,12] Joe Turner Blues (redux) [12] Ole Miss Blues (redux) [12] Feelin' Blues [13] 1924

The Basement BluesThe Chicago Gouge The Gouge of Armour Avenue Evolution of the Blues I'm Drinking from a Fountain That Never Runs Dry: Spiritual Atlanta Blues (Make Me One Pallet on Your Floor) [14] 1925

W.C. Handy's Famous Comic Blues for UkuleleW.C. Handy's Collection of Blues [12] When the Black Man Has a Nation of His Own [15] Bright Star of Hope [16,17] Friendless Blues [18] 1926

Goin' to See My SarahStomp Up-Stairs |

1926 (Cont.)

Golden BrownBlue Gummed Blues [14] 1927

Pasadena: Romanza OccidentalThe Birth of Jazz [10,20] The White Man Said 'Twas So, So It Must Be So [10] Golden Brown Blues: Song [19] 1928

Who's That Man? [21,22]1929

Wall Street Blues [23]1930

Chantez-les Bas: Creole BluesSomebody's Wrong About 'dis Bible [24] 1932

Way Down South Where the Blues BeganOpportunity [25] 1934

Annie LoveMozambique [26] 1935

‘Tis the Old Ship of Zion: Negro SpiritualVesuvius (There's a Red Glow in the Sky Above Vesuvius) [27] Negrita: Rumba [28] 1936

The Good Lord Sent Me You [29]1937

East St. LouisI'm Tellin' You In Front (So You Won't Feel Hurt Behind) [27,30] 1938

Beale Street Serenade [31,32]1940

Black Patti [10,20]Finis [27] Remembered [33,34] The Temple of Music [34] The Memphis Blues: Song (redux) [6] 1942

Woo-loo-moo-loo Blues [35]1951

The Big Stick Blues: March [6]

1. w/Harry Pace

2. w/George A. Norton 3. arr. Scott Joplin? 4. w/Douglass Williams 5. w/J.P. Schofield 6. w/J. Russel Robinson 7. w/Dorner Browne 8. w/Charles N. Hillman 9. w/William Braid Campbell 10. w/Chris Smith 11. w/J. Tim Brymn 12. w/Walter Hirsch 13. w/William Farrell 14. w/Dave Elman 15. w/J.M. Miller 16. w/Lillian A. Thorsten 17. w/Martha E. Koenig 18. w/Mercedes Gilbert 19. w/Langston Hughes 20. w/Henry Troy 21. w/Agnes Castleton 22. w/Spencer Williams 23. w/Margaret Gregory 24. w/Arthur J. Neale 25. w/Walter Malone 26. w/Arthur Porter 27. w/Andy Razaf 28. w/D'Artega 29. w/Elsie & Stella Francis 30. w/Russell Wooding 31. w/Gene Van Ormer 32. w/Porter Grainger |

Growing up in post-Civil War Alabama, the music of Black America and African heritage surrounded young William Handy. He was born in a log cabin in Florence, Alabama, the first of at least two surviving children of Charles Bernard Handy and Elizabeth Brewer, the other one being Charles Eugene (9/18/1889). Charles, Sr., was the pastor of a small church near Florence, but also worked as a cobbler or shoemaker. He had his son apprenticed in carpentry, shoemaking and plastering. After earning a little bit of money on the side, young Will brought home a guitar he had purchased, and his father immediately banned the "sinful thing" from the home. However, his parents were well enough off to get him music instruction, and after some failed organ lessons his first real instrument became the cornet.

Much of his true musical desire and even his performance activities remained hidden from his parents. The 1880 enumeration showed the family living near Florence in Lauderdale County, with Charles working as a shoe maker.

|

In his late teens Handy chose music as his vocation and avocation, somewhat against his father's wishes. He started touring the South with various troupes and shows. According to Handy in his autobiography, it was in 1892 in Mississippi that he had his first exposure to what we know now as Delta Blues as sung by local musicians. Many of the themes he heard, one in particular, would be revisited in later years and incorporated into his works. Handy also obtained a rudimentary teaching certificate in Birmingham, Alabama in 1892, and a teaching job in the same place. Poor wages, however, soon chased him off from this career track. His performance travels allowed him to play in one or more groups at the 1893 World'sColumbian Exposition in Chicago. Continuing his itinerant life after the event, Handy eventually took over one of the groups he traveled with in 1896, and over the next couple of years built up a repertoire of light classics, cakewalks, and early rags. Now and then he would run out of funds and remained stranded in one or another locale, working at any job to earn money to get to a place where he could start up again. He was married as well on July 19, 1898, to Elizabeth Virginia Price.

Most of the travels for Handy and his musicians were in the Mississippi Delta area through the early part of the new century. In 1900 Will and Liz (or Lizzie) were shown in the Rederal census in Florence, Alabama, boarding with a relative and Will's young brother. He listed his profession as musician. He had been traveling throughout the Midwest and South, and even to Cuba, but finally decided to stop the tiresome traveling for a while, settling with Liz back in Florence. This allowed him to teach music for a couple of years at the Alabama Agricultural and Mechanical University. The family eventually migrated from Alabama to Mississippi where he taught for another six years, finally finding themselves in Memphis, Tennessee late in the decade. He and Elizabeth eventually had several children, including Lucille Marie (6/29/1900), Katherine E. (6/20/1902), William Christopher, Jr. (8/15/1904), Elizabeth Virginia (11/17/1909) and Wyer Owens (1/12/1915). One other child died in infancy.

Over the next decade Handy worked sometimes as a teacher but largely as a musician or music director, building up his repertoire. Around 1902 he moved his family to Clarksdale, Mississippi, where he had more exposure to blues as played by a slide guitarist in a railroad station in nearby Tutwiler. In his autobiography he described the player as "a lean, loose-jointed negro [sic] who had commenced plucking a guitar beside me while I slept... His face had on it some of the sadness of the ages... As he played he pressed a knife on the strings of the guitar in the manner [later] popularised [sic] by Hawaiian guitarists who used steel bars." (In coming years a glass bottle neck would become the more popular sliding tool.) "His song, too, struck me instantly.. The singer repeated the line ['Goin' where the Southern cross' the Dog'] three times, accompanying himself on the guitar with the weirdest music I had ever heard... [but] the tune did stay in my mind." He also was exposed to a plucked string band in Mississippi that during a performance was clearly more popular than his own group, so he started arranging some of their older folk tunes for his own group.

"His song, too, struck me instantly.. The singer repeated the line ['Goin' where the Southern cross' the Dog'] three times, accompanying himself on the guitar with the weirdest music I had ever heard... [but] the tune did stay in my mind." He also was exposed to a plucked string band in Mississippi that during a performance was clearly more popular than his own group, so he started arranging some of their older folk tunes for his own group.

"His song, too, struck me instantly.. The singer repeated the line ['Goin' where the Southern cross' the Dog'] three times, accompanying himself on the guitar with the weirdest music I had ever heard... [but] the tune did stay in my mind." He also was exposed to a plucked string band in Mississippi that during a performance was clearly more popular than his own group, so he started arranging some of their older folk tunes for his own group.

"His song, too, struck me instantly.. The singer repeated the line ['Goin' where the Southern cross' the Dog'] three times, accompanying himself on the guitar with the weirdest music I had ever heard... [but] the tune did stay in my mind." He also was exposed to a plucked string band in Mississippi that during a performance was clearly more popular than his own group, so he started arranging some of their older folk tunes for his own group.Before 1905 the family moved to Hattiesburg, Mississippi, where William, Jr., was born. Then by 1908 or so they relocated to Memphis, Tennessee, where Will would see his earliest fame and cut his teeth as a composer, while learning many lessons about the music business and a Negro's plight in that business. The most active music scene in that town was along Beale Street near the Mississippi River, where the stevedores and riverboat workers would congregate and exchange ideas. While ragtime was enjoying great popularity throughout the country, and it became a part of his regular repertoire, Handy was ultimately more interested in the indigenous blues forms he had been hearing throughout the South in his early travels, and after studying and playing them for many years sought to get them down on paper with his own ideas incorporated.

Although Handy called himself "the Father of the Blues," he did not invent the blues form. He was at least the third or fourth composer to use the term "blues" in a song title that had some relation to that form of music, famously preceded three weeks by Artie Matthews' arrangement of Baby Seals Blues and potentially by Hart A. Wand's more to the point Dallas Blues, as well as I Got the Blues by Anthony Maggio from 1908. The 12-bar progression had also been used by Chris Smith and Hughie Cannon several years prior. Handy's first blues piece was actually first put down in 1909 when he was commissioned to write the music for a campaign song for the mayor of Memphis, Edward H. Crump. The song, which was a combination of sixteen-bar ragtime sections with hints of blues strains, was published as Mr. Crump and went over relatively well, but had no further distribution beyond the campaign. The 1910 census showed the growing Handy family in Memphis with Will listed as both a band master and a public service employee, evidently working in some capacity for the city to help support his growing family.

When the blues form was finally acknowledged as a publishable genre in 1912, Handy retooled the piece and had it self-published under the name Memphis Blues. This time it included "blue notes" (flatted thirds and sevenths) and a more definitive 12-bar blues section. One day when established composer and publisher Theron C. Bennett was visiting his Memphis representative and local bandleader Loren Z. Phillips at Bry's Department Store, he learned that Phillips had agreed to print Memphis Blues for Handy on speculation based on the clear potential of good sales, and was waiting for the first 1000 copies for distribution in Memphis. Based on Phillips' recommendation, Bennett told Handy he would act as a distribution agent offering him national exposure, a deal hard to turn down. Phillips and Bennett were both present with Handy when the initial delivery of 1000 copies was made. When Handy came to check on sales a week or so after the delivery, Phillips and Bennett showed him a stack of nearly the full 1000 copies, noting that sales were slow, and that perhaps the piece was too difficult for the average pianist to play. They encouraged him to simply sell the piece outright, which confused Handy, who knew the piece had been popular, but still agreed to a mere $50 for the plates and copyright. What the White pair did not tell the Black Handy was that this was the second stack of 1000 as the first 1000 copies had sold out very quickly. A few weeks later, another 10,000 copies were ordered with Bennett's imprint on the cover, and Phillips was offered a job as a wholesale manager. Within months, Bennett sold the Memphis Blues to publisher Joe Morris for a rather substantial amount. To make matters worse, Bennett's frequent lyricist George Norton was hired by Morris to add words to a song version of Memphis Blues which were only fair at best, and which Handy clearly objected to.

To make matters worse, Bennett's frequent lyricist George Norton was hired by Morris to add words to a song version of Memphis Blues which were only fair at best, and which Handy clearly objected to.

To make matters worse, Bennett's frequent lyricist George Norton was hired by Morris to add words to a song version of Memphis Blues which were only fair at best, and which Handy clearly objected to.

To make matters worse, Bennett's frequent lyricist George Norton was hired by Morris to add words to a song version of Memphis Blues which were only fair at best, and which Handy clearly objected to.This whole episode gave Handy a bad taste for the business, and a wary eye toward white publishers. As the song became more of a hit in the East, particularly through performances by James Reese Europe and his Clef Club bands, Handy's reputation grew in that area, with even the famed dance team of Vernon and Irene Castle crediting him with inventing the musical form of the Fox Trot. Although he kept writing, he was cautious in protecting his work. After writing a bit with local Memphis lyricist and business Harry H. Pace, who had provided the lyrics for his first song, he decided to form his own music company, which would soon be known as Handy and Pace Music. This firm, which published more than Handy's own material, was successful on its own merits for many years. Among the works they put in print were his already self-published Jogo Blues and their song The Girl You Never Have Met, both from 1913. Some of his pieces would soon find their way into the growing piano roll medium. But 1914 would turn out to be the real break-out year for Handy

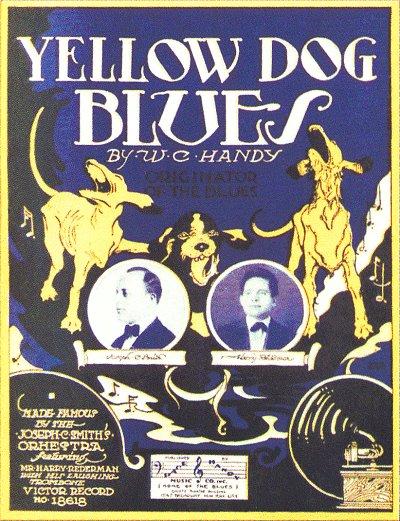

In 1913, Black Chicago composer Shelton Brooks wrote an iconic piece made famous by one his biggest musical supporters, the white singer Sophie Tucker. I Wonder Where My Easy Rider's Gone Today told the story of a young lady who put her trust into a horse race jockey, betting all she had based on his tips. On that particular day "Jockey Lee" did not race a horse, but instead raced off into the sunset with her money, begging the question asked in the title. Handy, seeing an opportunity to latch on to its popularity, and perhaps following the model of the Bill Bailey series of songs, answered the question in his own 1914 piece The Yellow Dog Rag, based on a previous tunes called the Pattona Rag, stating that Lee had gone down to "where the Southern cross' the Yellow Dog," the "Southern" being the Southern Railway and the "Yellow Dog" being the much smaller Yazoo Delta Railroad. It ultimately eclipsed the popularity of Brooks' original piece, and started a veritable flood of blues-styled compositions. But the best was still on the way.

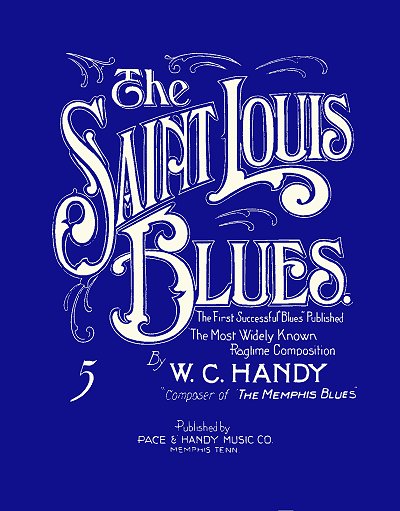

His new firm still struggling, Handy felt he still needed to write something of lasting substance, and create a hit at that time. He had often remembered a true-blue strain he had heard a woman sing some twenty years prior while he was down on his luck in and stranded in St. Louis. She was truly in pain, possibly abandoned by her man, and kept repeating the same strain, "I hate to see de evenin' sun go down." Bothered by distractions in a home with three young children, Handy rented a room down on Beale Street for one night. Filling out the mournful lament into a blues strain, he also utilized the opening strain from The Jogo Blues as a basis for the chorus, and added a tango interlude, the latter being a popular form emerging from New Orleans at that time. During that evening (as per his account), W.C. Handy produced this first true blues hit, music and lyrics complete, by the following morning, and soon Saint Louis Blues was in print as an instrumental and as a song. Unlike Memphis Blues, it took a bit longer to gain ground, but not too long. Ultimately, the flexibility with which the work could be interpreted, including varying tempos, orchestrations, and moods, made it the most recorded blues piece ever, and one of the top five pieces of music ever covered in 20th century history. As noted by jazz pianist Dave Brubeck in a conversation with the author in the mid-1980s, his take on the popularity of the piece was due to early "jazz fusion", since it combined traditional major blues with a minor tango, or more properly, habanera. A rhythm that likely originated in Africa, the habanera and its distinct melody are probably what made Saint Louis Blues instantly recognizable. Played as a fast one-step or a slow lament, it still resonates a century and more later.

He had often remembered a true-blue strain he had heard a woman sing some twenty years prior while he was down on his luck in and stranded in St. Louis. She was truly in pain, possibly abandoned by her man, and kept repeating the same strain, "I hate to see de evenin' sun go down." Bothered by distractions in a home with three young children, Handy rented a room down on Beale Street for one night. Filling out the mournful lament into a blues strain, he also utilized the opening strain from The Jogo Blues as a basis for the chorus, and added a tango interlude, the latter being a popular form emerging from New Orleans at that time. During that evening (as per his account), W.C. Handy produced this first true blues hit, music and lyrics complete, by the following morning, and soon Saint Louis Blues was in print as an instrumental and as a song. Unlike Memphis Blues, it took a bit longer to gain ground, but not too long. Ultimately, the flexibility with which the work could be interpreted, including varying tempos, orchestrations, and moods, made it the most recorded blues piece ever, and one of the top five pieces of music ever covered in 20th century history. As noted by jazz pianist Dave Brubeck in a conversation with the author in the mid-1980s, his take on the popularity of the piece was due to early "jazz fusion", since it combined traditional major blues with a minor tango, or more properly, habanera. A rhythm that likely originated in Africa, the habanera and its distinct melody are probably what made Saint Louis Blues instantly recognizable. Played as a fast one-step or a slow lament, it still resonates a century and more later.

He had often remembered a true-blue strain he had heard a woman sing some twenty years prior while he was down on his luck in and stranded in St. Louis. She was truly in pain, possibly abandoned by her man, and kept repeating the same strain, "I hate to see de evenin' sun go down." Bothered by distractions in a home with three young children, Handy rented a room down on Beale Street for one night. Filling out the mournful lament into a blues strain, he also utilized the opening strain from The Jogo Blues as a basis for the chorus, and added a tango interlude, the latter being a popular form emerging from New Orleans at that time. During that evening (as per his account), W.C. Handy produced this first true blues hit, music and lyrics complete, by the following morning, and soon Saint Louis Blues was in print as an instrumental and as a song. Unlike Memphis Blues, it took a bit longer to gain ground, but not too long. Ultimately, the flexibility with which the work could be interpreted, including varying tempos, orchestrations, and moods, made it the most recorded blues piece ever, and one of the top five pieces of music ever covered in 20th century history. As noted by jazz pianist Dave Brubeck in a conversation with the author in the mid-1980s, his take on the popularity of the piece was due to early "jazz fusion", since it combined traditional major blues with a minor tango, or more properly, habanera. A rhythm that likely originated in Africa, the habanera and its distinct melody are probably what made Saint Louis Blues instantly recognizable. Played as a fast one-step or a slow lament, it still resonates a century and more later.

He had often remembered a true-blue strain he had heard a woman sing some twenty years prior while he was down on his luck in and stranded in St. Louis. She was truly in pain, possibly abandoned by her man, and kept repeating the same strain, "I hate to see de evenin' sun go down." Bothered by distractions in a home with three young children, Handy rented a room down on Beale Street for one night. Filling out the mournful lament into a blues strain, he also utilized the opening strain from The Jogo Blues as a basis for the chorus, and added a tango interlude, the latter being a popular form emerging from New Orleans at that time. During that evening (as per his account), W.C. Handy produced this first true blues hit, music and lyrics complete, by the following morning, and soon Saint Louis Blues was in print as an instrumental and as a song. Unlike Memphis Blues, it took a bit longer to gain ground, but not too long. Ultimately, the flexibility with which the work could be interpreted, including varying tempos, orchestrations, and moods, made it the most recorded blues piece ever, and one of the top five pieces of music ever covered in 20th century history. As noted by jazz pianist Dave Brubeck in a conversation with the author in the mid-1980s, his take on the popularity of the piece was due to early "jazz fusion", since it combined traditional major blues with a minor tango, or more properly, habanera. A rhythm that likely originated in Africa, the habanera and its distinct melody are probably what made Saint Louis Blues instantly recognizable. Played as a fast one-step or a slow lament, it still resonates a century and more later.Handy's new fame put him in the forefront of blues presenters. His band made many recordings of his and other composers' compositions, and he even ran his own blues record label for a while. Even so, he occasionally criticized the format as being a "primitive music" that suffered from "disturbing monotony". But as long as the dollars kept rolling in, he kept on championing the genre. Handy's Saint Louis Blues quickly became the standard by which other blues were measured.

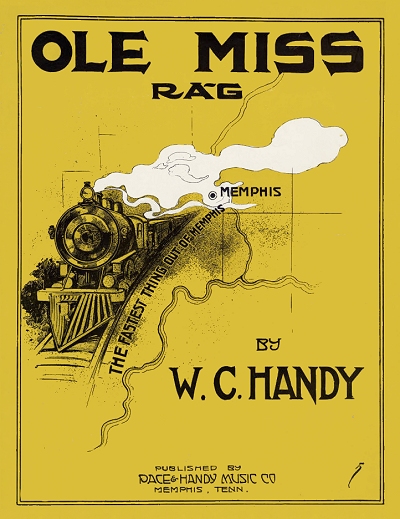

By mid-1915, Handy was starting to frequent Manhattan, New York, where he would eventually relocate and set up an office for his publishing firm. It was during his early time there that one of his more curious associations was created, although the full circumstances are still not known. Handy's reputation quickly helped him to forge new relationships with James Reese Europe and other New York City musicians who had been playing his works. On the periphery of this group was the aging and increasingly ill classic ragtime composer Scott Joplin, who by this time was teaching piano, and ostensibly no longer writing anything that would be published. In the spring of 1916, Joplin recorded a series of piano rolls, most of them for the Connorized label. Among them was the tune Ole Miss Rag. As all of the other pieces had been by Joplin himself, this very recording brings up a number of questions and suggestions. First, that his name was applied to a Connorized arrangement (albeit one that sounds hand-played) to increase sales. Secondly, that Joplin was doing some kind of favor for Handy. Or, thirdly, that Joplin had a hand in this work, either as a silent collaborator or arranger. There is some merit to the third argument given that Handy's post-1912 pieces were all blues, not rags, but even with forensic investigation into the piece itself, such postulation remains speculative. Joplin would die within the year, so further association between the two was minimal at best.

Handy's reputation quickly helped him to forge new relationships with James Reese Europe and other New York City musicians who had been playing his works. On the periphery of this group was the aging and increasingly ill classic ragtime composer Scott Joplin, who by this time was teaching piano, and ostensibly no longer writing anything that would be published. In the spring of 1916, Joplin recorded a series of piano rolls, most of them for the Connorized label. Among them was the tune Ole Miss Rag. As all of the other pieces had been by Joplin himself, this very recording brings up a number of questions and suggestions. First, that his name was applied to a Connorized arrangement (albeit one that sounds hand-played) to increase sales. Secondly, that Joplin was doing some kind of favor for Handy. Or, thirdly, that Joplin had a hand in this work, either as a silent collaborator or arranger. There is some merit to the third argument given that Handy's post-1912 pieces were all blues, not rags, but even with forensic investigation into the piece itself, such postulation remains speculative. Joplin would die within the year, so further association between the two was minimal at best.

Handy's reputation quickly helped him to forge new relationships with James Reese Europe and other New York City musicians who had been playing his works. On the periphery of this group was the aging and increasingly ill classic ragtime composer Scott Joplin, who by this time was teaching piano, and ostensibly no longer writing anything that would be published. In the spring of 1916, Joplin recorded a series of piano rolls, most of them for the Connorized label. Among them was the tune Ole Miss Rag. As all of the other pieces had been by Joplin himself, this very recording brings up a number of questions and suggestions. First, that his name was applied to a Connorized arrangement (albeit one that sounds hand-played) to increase sales. Secondly, that Joplin was doing some kind of favor for Handy. Or, thirdly, that Joplin had a hand in this work, either as a silent collaborator or arranger. There is some merit to the third argument given that Handy's post-1912 pieces were all blues, not rags, but even with forensic investigation into the piece itself, such postulation remains speculative. Joplin would die within the year, so further association between the two was minimal at best.

Handy's reputation quickly helped him to forge new relationships with James Reese Europe and other New York City musicians who had been playing his works. On the periphery of this group was the aging and increasingly ill classic ragtime composer Scott Joplin, who by this time was teaching piano, and ostensibly no longer writing anything that would be published. In the spring of 1916, Joplin recorded a series of piano rolls, most of them for the Connorized label. Among them was the tune Ole Miss Rag. As all of the other pieces had been by Joplin himself, this very recording brings up a number of questions and suggestions. First, that his name was applied to a Connorized arrangement (albeit one that sounds hand-played) to increase sales. Secondly, that Joplin was doing some kind of favor for Handy. Or, thirdly, that Joplin had a hand in this work, either as a silent collaborator or arranger. There is some merit to the third argument given that Handy's post-1912 pieces were all blues, not rags, but even with forensic investigation into the piece itself, such postulation remains speculative. Joplin would die within the year, so further association between the two was minimal at best.For the next several years, Handy would not only continue composing, often with a variety of other lyricists and composers, but arranging for bands, orchestras, and print, particularly reviving old Negro spirituals and field songs. His next hit was Beale Street Blues with mildly questionable lyrics concerning life on that Memphis strand, even suggesting the possibility of the upcoming Volstead Act and National Prohibition with the line "the river's wet, but Beale Street's done gone dry." It was recorded by many early blues singers and bands, as well as on a few piano roll renditions. On his WWI draft card Handy referred to himself as a music publisher, still in business with Harry Pace.

Now regarded highly for his perseverance in making published and performed blues into a legitimate music form, and having great success with his own Pace & Handy Orchestra, Will had become somewhat of a distinguished spokesman for the genre, and was called upon by the Music Trade Review to write an article on "The Origin and Evolution of the Blues" for their December 14, 1918, edition. It was one of the first steps for what would eventually become a well-known published tome on the topic, and is excerpted here:

As I am more often than not given credit for being the "creator of blues," many people in the trade, including historians, publishers and teachers, etc., have requested me at different times to state how I was led to write such compositions.

As a boy I worked very hard, but like all my people, I felt the need of melodies and took part in many musical entertainments, later becoming a member of a not too successful Glee Club. There was, of course, no financial remuneration in these affairs, and there were times when I was hard pressed for funds. At one of these periods, for they came often, a friend of mine encouraged me to follow out my desires along musical lines. I had intended to purchase a cornet, but he said, "Son, you go get yourself a banjo. That's the colored man's instrument." I, however, bought a cornet with the money I had been saving for quite a long while. I progressed very nicely and at the age of twenty years I became the leading band-master in a minstrel show.

At one of these periods, for they came often, a friend of mine encouraged me to follow out my desires along musical lines. I had intended to purchase a cornet, but he said, "Son, you go get yourself a banjo. That's the colored man's instrument." I, however, bought a cornet with the money I had been saving for quite a long while. I progressed very nicely and at the age of twenty years I became the leading band-master in a minstrel show.

At one of these periods, for they came often, a friend of mine encouraged me to follow out my desires along musical lines. I had intended to purchase a cornet, but he said, "Son, you go get yourself a banjo. That's the colored man's instrument." I, however, bought a cornet with the money I had been saving for quite a long while. I progressed very nicely and at the age of twenty years I became the leading band-master in a minstrel show.

At one of these periods, for they came often, a friend of mine encouraged me to follow out my desires along musical lines. I had intended to purchase a cornet, but he said, "Son, you go get yourself a banjo. That's the colored man's instrument." I, however, bought a cornet with the money I had been saving for quite a long while. I progressed very nicely and at the age of twenty years I became the leading band-master in a minstrel show.I had quite a taste at this time for classical music and I was much given to reading, including the history and lives of master musicians. This included, of course, folk songs, and I found these master composers had built their greatest work on the lives of the people of which they were a part. Primitive melodies of the Southern negro [sic] appealed to me as having qualities worth while writing into a distinct line of music. I quit the show business, went South, and stayed three years in Mississippi studying the plantation melodies. I then organized an orchestra in Memphis, Tenn., and featured these melodies at dances and other public affairs. It was not long before they became popular, and I had ten such organizations.

These melodies were such successes that I then decided to publish at least a few of them. Being the originator of the blue idea, I wish to give to those interested this bit of information:

The name Blues is not derived from the blue notes contained therein, as is erroneously stated by imitators of this style.

Frederick Douglass, the ex-slave and statesman, in his autobiography, has this to say: "It is not inconsistent with the constitution of human mind that avails itself of one and the same method of expressing opposite emotions."

The songs of the slaves represented their sorrows rather than their joys. Like tears, they were a relief to an aching heart. The sorrow songs of the slaves we call jubilee melodies. The happy-go-lucky songs of the Southern Negro we call "blues."

The tendency to avoid the seventh tone of the scale in these melodies and to overdraw the minor third gives to this form of composition a weird effect when heard, and although the imagination is drawn on to connect these blues with their African origin, it is a fact that most primitive peoples carefully avoided the seventh tone of the scale...

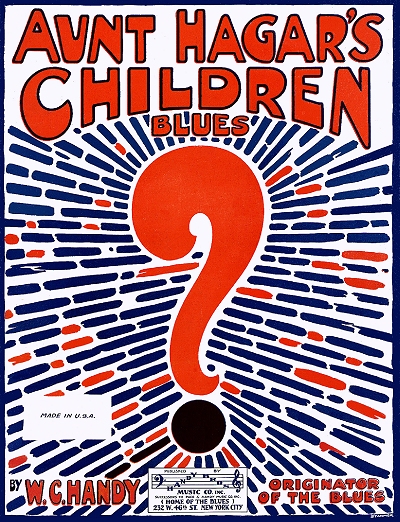

For the January 1920 census, taken in Manhattan, he had changed this to music conductor, with his daughter Lucille working as a stenographer for his publishing firm. Around 1920, Harry Pace left the Pace and Handy firm to form Black Swan Records in an effort to facilitate Black artists recording Black-composed pieces. William’s brother Charles joined him, creating the Handy Brothers Music Company. Lucille would also contribute to their inventory, submitting Sweet Dream Blues in 1921. Now living in a very nice New York city home and riding high on the growing success of Saint Louis Blues, Handy focused much of his effort on trying to tell the story of the origins of the blues in addition to writing more of them. His next hit of substances was Aunt Hagar's Children Blues in 1901, which was morphed into the song Aunt Hagar's Blues in 1921 with veteran black lyricist Chris Smith.

William’s brother Charles joined him, creating the Handy Brothers Music Company. Lucille would also contribute to their inventory, submitting Sweet Dream Blues in 1921. Now living in a very nice New York city home and riding high on the growing success of Saint Louis Blues, Handy focused much of his effort on trying to tell the story of the origins of the blues in addition to writing more of them. His next hit of substances was Aunt Hagar's Children Blues in 1901, which was morphed into the song Aunt Hagar's Blues in 1921 with veteran black lyricist Chris Smith.

William’s brother Charles joined him, creating the Handy Brothers Music Company. Lucille would also contribute to their inventory, submitting Sweet Dream Blues in 1921. Now living in a very nice New York city home and riding high on the growing success of Saint Louis Blues, Handy focused much of his effort on trying to tell the story of the origins of the blues in addition to writing more of them. His next hit of substances was Aunt Hagar's Children Blues in 1901, which was morphed into the song Aunt Hagar's Blues in 1921 with veteran black lyricist Chris Smith.

William’s brother Charles joined him, creating the Handy Brothers Music Company. Lucille would also contribute to their inventory, submitting Sweet Dream Blues in 1921. Now living in a very nice New York city home and riding high on the growing success of Saint Louis Blues, Handy focused much of his effort on trying to tell the story of the origins of the blues in addition to writing more of them. His next hit of substances was Aunt Hagar's Children Blues in 1901, which was morphed into the song Aunt Hagar's Blues in 1921 with veteran black lyricist Chris Smith.Very little in the way of best sellers came until 1924 when he revived the old song Make Me a Pallet on the Floor with reshaped lyrics by Dave Elman. (Note that Ferdinand "Jelly Roll" Morton recorded a version of this piece for the Library of Congress in 1938 with lyrics that were sexually profane at best, so if they were the original strains, Elman had quite a job in cleaning them up.) During this time frame, Charles Handy was also making a name for himself as a capable composer and lyricist, teaming up with several other artists, though curiously rarely published by the family firm. One of his 1923 pieces was later paraphrased as an iconic 1950s album on the Good Time Jazz label, I'm Gonna Tear Your Playhouse Down.

In 1924 Handy joined ASCAP, formed a decade before to help further the cause of music composers and artists. Then in 1926 he published his first book, Blues: An Anthology: Complete Words and Music of 53 Great Songs. This is considered the first analytical look at the genre, and a groundbreaking effort. The next few years saw diminishing releases of new material mixed with revived spirituals. One breakthrough, following bandleader Paul Whiteman's historic jazz concert in the established music venue of Aeolian Hall in 1924, was an invitation for Handy to play with an orchestra and a group of Jubilee Singers at no less than Carnegie Hall in May 1928. Also participating in the program were composer James P. Johnson who was represented by his "Negro Rhapsody" Yamecraw, and the soon-to-be-established pianist and composer Thomas "Fats" Waller who performed the solos of the work in Johnson's absence. Among the vocalists were singers J. Rosamond Johnson and Taylor Gordon. The overall affair was well reviewed, but the particular highlights of the evening were performances of Handy's now-established blues hits of the prior decade. In 1930, still residing in Manhattan, Handy listed himself as the manager of a music office for the census, which could imply either publishing or theatrical, if not both. Daughter Katherine was now working for his firm as well. Handy had been involved with recording and consulting with early movie shorts that featured blues music, including his now famous Saint Louis Blues starring hard-living dynamic Black singer Bessie Smith.

In the 1930's when the playing jobs for bands, and even older pianists, started to disappear, Handy wrote his autobiography, Father of the Blues. [The author is unclear as to whether Handy or his publisher chose the title, but feels that a more accurate description might respectfully be "Stenographer of the Blues," with no deference intended.] Three other books also appeared, including a collection of Negro spirituals, Unsung Americans Sing (1944) including sketches of selected race musicians, and Negro Authors and Composers of the United States. On a 1938 Ripley's Believe It Or Not radio program, Handy's role was lauded as not only the father, but the inventor of the blues. This incensed one of its listeners, no less than "Jelly Roll" Morton, who felt that he knew better who had done what. In a letter that was sent to Ripley and later read on the air, Morton made it clear that it was more likely HE who had introduced the blues, not to mention, jazz, to the world, but stopped short of claiming actual invention rights. In truth, no one musician invented the genre, but both certainly spread it throughout the world. While also not the originator of the blues, Handy was certainly its most effective spokesperson, and continued to promote the music form and push for its inclusion in the early 1900s American music vernacular.

By the late 1930s the Handys had moved to a fine home Harlem. William had been widowed after Elizabeth’s death in 1947, and by the time of the 1940 enumeration taken in Harlem, he was living with his daughter Katherine, her husband Homer Lewis, and their young son Homer, Jr. Handy was listed as a musical publisher in that enumeration, but this was more of an indirect role that he played by that time. In 1943, Will suffered a fall from a subway platform which resulted in blindness, all but incapacitating him, and stopping his output and public appearances.

William eventually moved to Yonkers, and then remarried in 1954 to Irma Louis Logan who had been his personal secretary, and who had personally helped him through many of the issues of blindness. In his 80th year in 1955 Handy suffered a debilitating stroke that confined him to a wheelchair. He finally died of acute bronchial pneumonia at 84 years old. That same year a movie of his life, St. Louis Blues, was released starring Nat King Cole as Handy, as well as many other prominent Black musicians of the time. They and tens of thousands others attended his funeral service both in Abyssinian Baptist Church in Harlem and overflowing on a large stretch of 138th street. Despite a request from the City of Memphis, he was laid to rest in Woodlawn Cemetery in New York in the South Bronx. A memorial and statue were erected on Beale Street in Memphis. Handy’s legacy legacy will forever remain with us on a daily basis, as the influence of his blues can be felt and heard in Gospel, Country, Rhythm & Blues, and Rock and Roll music, all truly American music forms originating from the time of ragtime and blues.