A mouthful of name from the day he was born William Henry Joseph Bonaparte Bertholf Smith long maintained that he was four years younger than his actual age, but the 1893 birth year is accurate as per government and other official records. Why he later cited 1897 is unclear, but then again many different aspects of his life as told in interviews and in his biography are also often at odds with the facts. Such stories should be taken as perhaps just somewhat true, with some of the truth simply withheld for whatever reasons he had to do so. The same goes for the November 23 date, which is the one listed on his draft record. The Social Security database had November 24, 1893, as the date and his autobiography states November 25. However, November 23 is the earliest confirmation and historically this has usually been considered the most accurate. It may also be a variance due to the difference between Jewish birth times, noting the date change after sundown, and the traditional calendar, where the date changes at midnight.

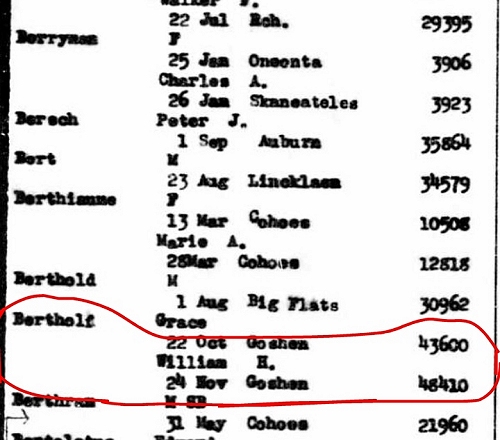

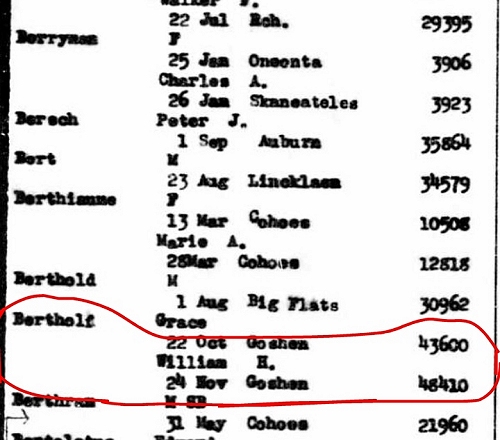

William was born in Goshen, New York, to a white father cited in his autobiography as Frank Bertholoff and Christian mother Ida Oliver who was a combination of "Spanish, Negro and Mohawk Indian blood." In his autobiography, Willie remembered, likely from what was conveyed to him by his mother, that "Frank Bertholoff was a light skinned playboy who loved his liquor, girls and gambling." Note that there was nobody by the usually cited last name of Bertholoff listed in the entirety of the accumulative historical United States census records, but there were a handful named Bertholof, making it a somewhat more likely last name, and even that name appears with that spelling only in the 1880 enumeration. While there were three Bertholofs living in Goshen as of 1880, one of them being Edwin W. Bertholof, a more credible possibility is electrician Frank Bertholf, born in mid-1862, who was living in nearby Monroe, New York, 11 miles to the southeast for most of his life. He was shown to be single, not divorced, in the 1900 enumeration, which may have been either a choice or perhaps even a truth. The Bertholf family was living in Monroe, not Goshen, in 1880 under the name Bortholf, but the challenging handwriting more likely indicates Bertholf. Overall Willie's account of the last name may be called a bit into question just as much as that enumerator's spelling. Frank Bertholf can be traced up through his death in late 1934, just 8 months after he was married at age 71. It is possible that he and Ida were never legally married as no record could be found for the 1890s. It is also probable that Willie's only real knowledge of his birth father was through his mother, and therefore the name was altered a bit in translation from his early memories. In addition, a recently uncovered birth record, albeit with a November 24, 1893 date, positively shows him born in Goshen under the name William H. Bertholf. For this essay, Frank Bertholf will be assumed as the most correct probable person to have been Willie's birth father.

While there were three Bertholofs living in Goshen as of 1880, one of them being Edwin W. Bertholof, a more credible possibility is electrician Frank Bertholf, born in mid-1862, who was living in nearby Monroe, New York, 11 miles to the southeast for most of his life. He was shown to be single, not divorced, in the 1900 enumeration, which may have been either a choice or perhaps even a truth. The Bertholf family was living in Monroe, not Goshen, in 1880 under the name Bortholf, but the challenging handwriting more likely indicates Bertholf. Overall Willie's account of the last name may be called a bit into question just as much as that enumerator's spelling. Frank Bertholf can be traced up through his death in late 1934, just 8 months after he was married at age 71. It is possible that he and Ida were never legally married as no record could be found for the 1890s. It is also probable that Willie's only real knowledge of his birth father was through his mother, and therefore the name was altered a bit in translation from his early memories. In addition, a recently uncovered birth record, albeit with a November 24, 1893 date, positively shows him born in Goshen under the name William H. Bertholf. For this essay, Frank Bertholf will be assumed as the most correct probable person to have been Willie's birth father.

While there were three Bertholofs living in Goshen as of 1880, one of them being Edwin W. Bertholof, a more credible possibility is electrician Frank Bertholf, born in mid-1862, who was living in nearby Monroe, New York, 11 miles to the southeast for most of his life. He was shown to be single, not divorced, in the 1900 enumeration, which may have been either a choice or perhaps even a truth. The Bertholf family was living in Monroe, not Goshen, in 1880 under the name Bortholf, but the challenging handwriting more likely indicates Bertholf. Overall Willie's account of the last name may be called a bit into question just as much as that enumerator's spelling. Frank Bertholf can be traced up through his death in late 1934, just 8 months after he was married at age 71. It is possible that he and Ida were never legally married as no record could be found for the 1890s. It is also probable that Willie's only real knowledge of his birth father was through his mother, and therefore the name was altered a bit in translation from his early memories. In addition, a recently uncovered birth record, albeit with a November 24, 1893 date, positively shows him born in Goshen under the name William H. Bertholf. For this essay, Frank Bertholf will be assumed as the most correct probable person to have been Willie's birth father.

While there were three Bertholofs living in Goshen as of 1880, one of them being Edwin W. Bertholof, a more credible possibility is electrician Frank Bertholf, born in mid-1862, who was living in nearby Monroe, New York, 11 miles to the southeast for most of his life. He was shown to be single, not divorced, in the 1900 enumeration, which may have been either a choice or perhaps even a truth. The Bertholf family was living in Monroe, not Goshen, in 1880 under the name Bortholf, but the challenging handwriting more likely indicates Bertholf. Overall Willie's account of the last name may be called a bit into question just as much as that enumerator's spelling. Frank Bertholf can be traced up through his death in late 1934, just 8 months after he was married at age 71. It is possible that he and Ida were never legally married as no record could be found for the 1890s. It is also probable that Willie's only real knowledge of his birth father was through his mother, and therefore the name was altered a bit in translation from his early memories. In addition, a recently uncovered birth record, albeit with a November 24, 1893 date, positively shows him born in Goshen under the name William H. Bertholf. For this essay, Frank Bertholf will be assumed as the most correct probable person to have been Willie's birth father.Smith was added to Willie's expanding name around 1896 after his mother, who had thrown his drinking and carousing father out when Willie was around two-years-old, was remarried to teamster mechanic John Smith from Patterson, New Jersey. He had an older brother, Jerome, although which parent Jerome is associated with is unclear. Ida and John also had another son, Robert, in 1897. They were all found residing in Newark, New Jersey, for the 1900 census along with Willie's grandmother, Anna Oliver. This is clearly at variance with some traditional sources that claim that Frank died in 1901 and his mother married Smith after that time.

Willie reportedly started playing at the age of 8, perhaps sooner, but came by it naturally as his mother played the organ and his maternal grandmother both organ and guitar. The area of Newark they were in, combined with some knowledge of his paternal heritage, influenced Willie's religious sensibilities at some point. So he was liberally exposed not only to ragtime as it progressed through the 1900s and 1910s, and blues as sung by local dock workers, but the music of both of the faiths of his heritage. He very much enjoyed the Negro spirituals and black gospel music of the church, but also the plaintive melodic lines and harmonies of Hebrew music. As his mother was a laundress at that time, she took care of the clothes of more than one prosperous Jewish family. Willie would deliver the clothes for her, and one family in particular embraced him, and even invited him to be part of the Saturday Hebrew classes taught by a rabbi in their home. On many occasions the rabbi would have one on one sessions with the boy. Willie soon embraced Judaism as his faith, and eventually became one of the more prominent figures in his local synagogue (at least by his own account). He reportedly had his Bar Mitzvah around 1906 in a Newark synagogue, further reinforcing the 1893 birth date.

The young student's semi-formal training in piano enhanced his musical exposure as he learned the music many European composers, particularly fond of contemporary French impressionists like Debussy and Ravel. Harmony and theory training were also evident in many of his later works and his arrangements of popular tunes which included dense harmonic content and tricky chord changes. He also credits some advice from his mother which suggested variety: "I used to dance and my mother used to say, 'Don't go up the right side and come back on the right side, go up the right side and come back on the left -- alternate.'" And that he did.

When Smith was 17 he saw black entertainer Bert Williams in Mr. Lode of Koal when it came to Newark. It helped spur his desire to also entertain, although in a more intimate way than on stage. Soon he was playing in saloons and brothels in Newark along the shore of New York Harbor and the Hudson, working in both semi-classical tunes and popular works of the day in his repertoire. By 1911 he was performing at Randolph's Saloon, one of the more prominent Newark venues. It was in Randolph's in 1913 where Willie met Harlem stride player Charles Luckeyth (Luckey) Robert, who he deemed a "lemon pool player" but a good pianist. After hearing Pork and Beans and Junk Man Rag, he added those to his permanent repertoire.

The following year Smith met future stride pianist James P. Johnson in Newark who was playing semi-classics by Victor Herbert and Rudolph Friml in addition to ragtime. It was likely that Johnson exposed Willie to some of the clubs in the "Hell's Kitchen" part of New York where he was also cutting his teeth at that time. This inspired Smith's desire to perform even further, and he bolstered his music reading skills with lessons from a Newark Vaudeville pianist around the same time Johnson was taking lessons from another fine New York pianist.

Finally as a confident young adult in the summer of 1915, Willie ventured to Atlantic City to play in the tenderloin district. Also appearing there was Eubie Blake, six years his senior and on his way to bigger things in Manhattan. Willie started playing breaks for Eubie at Kelly's Cafe, a practice that he said many pianists feared. Some of them, he stated, wouldn't even drink during their four to six hour shift, and they were afraid to even get up and take a bathroom break because if someone else came along who played better during their absence they may never get their position back. This may not have been the case with Eubie, but by the end of the summer, Smith had replaced Blake at Kelly's piano. He continued there for a while, but eventually was back in Newark, often venturing over to New York City where he was gaining a reputation as a fierce pianist.

In late 1915 Smith married another pianist and entertainer he had been acquainted with, Blanche (Howard) Merrill (who in the early 1960s would record a honky-tonk/ragtime album as Grandma Merrill). Their relationship was often at odds from the beginning, in part because she was white. Even in the somewhat liberal environment of New York miscegenation was still a lifestyle that was met with scorn. Blanche and Willie separated from their sometimes contentious union sometime in mid-1917, but it was not yet over.

Willie claims to have joined the United States Army even before the declaration of war in April 1917 was out of the mouth of President Woodrow Wilson, but official records indicate otherwise. He was actually inducted through the draft in November of 1917 and sent to the 92nd Division, 153rd Negro Brigade, 350th Field Artillery, known as "The Black Devils". Among those in this brigade were composer J. Tim Brymn who led the 70 piece regimental group, The Black Devil Orchestra. Given that pianos were not so portable, Smith became a drummer with the group. They were described as "a military symphony engaged in a battle of jazz." It was in France that he most likely earned his nickname of "The Lion." Although there are many versions of how it came, virtually all told by Willie, it was said that he fought fiercely and quite bravely like a lion, something that can be ascertained from the decorations he received for his conduct in the field as a heavy artillery gunner. The most credible story is that after having fought in the trenches for 49 days without a break, he volunteered to man the difficult behemoth 75-millimeter French built cannon, a powerful and noisy instrument of destruction that helped the Allies win the entrenched battles of Verdun and The Marne. It was allegedly his Colonel that dubbed him as "The Lion."

He was actually inducted through the draft in November of 1917 and sent to the 92nd Division, 153rd Negro Brigade, 350th Field Artillery, known as "The Black Devils". Among those in this brigade were composer J. Tim Brymn who led the 70 piece regimental group, The Black Devil Orchestra. Given that pianos were not so portable, Smith became a drummer with the group. They were described as "a military symphony engaged in a battle of jazz." It was in France that he most likely earned his nickname of "The Lion." Although there are many versions of how it came, virtually all told by Willie, it was said that he fought fiercely and quite bravely like a lion, something that can be ascertained from the decorations he received for his conduct in the field as a heavy artillery gunner. The most credible story is that after having fought in the trenches for 49 days without a break, he volunteered to man the difficult behemoth 75-millimeter French built cannon, a powerful and noisy instrument of destruction that helped the Allies win the entrenched battles of Verdun and The Marne. It was allegedly his Colonel that dubbed him as "The Lion."

He was actually inducted through the draft in November of 1917 and sent to the 92nd Division, 153rd Negro Brigade, 350th Field Artillery, known as "The Black Devils". Among those in this brigade were composer J. Tim Brymn who led the 70 piece regimental group, The Black Devil Orchestra. Given that pianos were not so portable, Smith became a drummer with the group. They were described as "a military symphony engaged in a battle of jazz." It was in France that he most likely earned his nickname of "The Lion." Although there are many versions of how it came, virtually all told by Willie, it was said that he fought fiercely and quite bravely like a lion, something that can be ascertained from the decorations he received for his conduct in the field as a heavy artillery gunner. The most credible story is that after having fought in the trenches for 49 days without a break, he volunteered to man the difficult behemoth 75-millimeter French built cannon, a powerful and noisy instrument of destruction that helped the Allies win the entrenched battles of Verdun and The Marne. It was allegedly his Colonel that dubbed him as "The Lion."

He was actually inducted through the draft in November of 1917 and sent to the 92nd Division, 153rd Negro Brigade, 350th Field Artillery, known as "The Black Devils". Among those in this brigade were composer J. Tim Brymn who led the 70 piece regimental group, The Black Devil Orchestra. Given that pianos were not so portable, Smith became a drummer with the group. They were described as "a military symphony engaged in a battle of jazz." It was in France that he most likely earned his nickname of "The Lion." Although there are many versions of how it came, virtually all told by Willie, it was said that he fought fiercely and quite bravely like a lion, something that can be ascertained from the decorations he received for his conduct in the field as a heavy artillery gunner. The most credible story is that after having fought in the trenches for 49 days without a break, he volunteered to man the difficult behemoth 75-millimeter French built cannon, a powerful and noisy instrument of destruction that helped the Allies win the entrenched battles of Verdun and The Marne. It was allegedly his Colonel that dubbed him as "The Lion."By the end of his tour of duty Smith had officially risen to the rank of Corporal, although he recalled that he actually made it as far as Sergeant. After the Armistice of November 1918 Willie and many of his peers stayed on duty in France for several more months, spending much of his time playing in dance halls and, perhaps, brothels. He was finally honorably discharged in mid-1919, then returned to New York City to resume his fledgling playing career. One of Smith's first jobs was at Leroy's Cabaret in Harlem, where he supposedly lived for a time in the boarding house of Lottie Joplin, Scott Joplin's widow [not fully confirmed]. However, by the time of the January 1920 census he was shown living once again with his wife Blanche on West Street in Newark, being the only person of color in their apartment building. Willie was listed as a musician in a cabaret (the sad replacement for the recently defunct saloon) and Blanche as a musician in a show house. His age at 26 was still in line with the 1893 birth year. When they finally broke up for good is not certain, but they appear to have never been legally divorced.

With his new nickname and even more confidence and bravado, Willie "The Lion" Smith didn't just play at venues; he took them over for the night, working as a sort of master of ceremonies at times. He was only somewhat tolerant of other pianists, and sometimes when they would sit down he'd interrupt them after a few bars and push them aside saying something like "Why don't you try this," or "This is how it should be done." That they were acknowledged by him at all helped to take away the sting. The quality of his playing also, for most, justified the ego that accompanied it.

Willie also set some historical precedents, and became an accompanist for blues singer Mamie Smith, performing on her first hit record in 1920, Crazy Blues, an iconic piece by composer Perry Bradford.

This was the first commercial recording of Negro blues released to the public. For that session he received a mere $25. The song helped to spark a 1920s craze for "authentic Negro blues" on race records, and Willie worked on many of them, although not always credited. Mamie decided to tour her act on the Vaudeville circuit, but Smith declined an invitation, preferring to stay at home in New Jersey. The following year saw the highly successful debut of Shuffle Along by Noble Sissle and Eubie Blake, and things started looking even rosier for pianists like Willie as a result of that popularity. It helped spur the proliferation of dance clubs in Harlem and even south of the district where people could go to dance or listen to black music.

|

It was in 1921 that James P. brought along a 17-year-old pupil of his to meet Smith, one Thomas Waller. The youngster who would eventually be known as Fats Waller due to his considerable size was evidently taken with Willie's dynamic style, and soon attempted to match it with quite a bit of success. They rapidly became life-long friends, and Waller, Johnson and Smith ruled the roost of pianists playing the style that was becoming known as Harlem Stride. Others who came to listen to Willie perform included composer George Gershwin and Washington DC native Edward "Duke" Ellington.

In spite of the accolades of his peers who looking back called him the "musician's musician," Smith was still somewhat obscure to the public, having not done any solo recording work or composition. He did finally decide to venture out in late 1922 through 1923, working with the Theatre Owners Booking Association (TOBA) and Orpheum Vaudeville circuits, staying for around six months in Chicago to perform there. By the time he returned to Harlem, now in the fourth year of prohibition with a population of over 300,000, he found that many of the better spots were being taken over by the gangster element. This did not deter him however, as he was as tough as any of them, and had many friends throughout New York. One of those had become Gershwin, who after the premiere of Rhapsody in Blue in February of 1924 invited Willie, Jimmy Johnson and Fats to a celebration party. This exposure to the white patrons of the musical arts helped to land them frequent jobs at society parties for many years thereafter.

Finally in 1925 Willie started recording his own piano style thanks to help from composer Clarence Williams. Keep Your Temper, recorded twice with small ensembles, was one of his first releases and did fairly well, particularly in New York. It got him into even more places, including the Rhythm Club where he would jam with notables like Sidney Bechet, Louis Metcalf, Joe Smith, Johnny Hodges, Louis Armstrong, and many more. Willie also played briefly on Broadway for the drama Four Walls. Another frequent venue and necessity was the Harlem Rent Party, usually held to raise rent money for a needy family in the community by charging admission. The big three of stride were frequently featured at these events, and they tried to constantly upstage each other in cutting contests both on and off the piano, including many wild reports of bedroom antics, common in the lifestyle of many pianists at that time. At times, the Duke would also join in.

A transplant from Washington, DC, Ellington came to New York in the early 1920s to see how he measured up against the other pianists, and to secure steady work. He and Willie hit it off famously right away. Once Ellington gained enough confidence in his relative abilities against the Harlem gang, Duke remembered engaging Willie in friendly cutting contests at rent parties that would last for up to five hours.

"We would embroider the melodies with our own original ideas and try to develop patterns that had more originality than those played before us. Sometimes it was just a question of who could think up the most patterns within a given time. It was pure improvisation. You had to have your own individual style and be able to play in all the keys. In those days we could all copy each other's shouts by learning them by ear. Sometimes, in order to keep the others from picking up too much of my stuff, I'd perform in the hard keys, B major and E major."

|

As for the parties, Willie wrote that "they would crowd a hundred or more people into a seven-room railroad flat, and the walls would bulge - some of the parties spread to the halls and all over the building." Some of them would last well into the next day, and usually everybody in the building was invited. Players like Johnson had advance men, ad hoc agents, who would locate all of the rent parties happening in one evening, then schedule their player to attend one or the other. Even though these events started out as a charity in the 1910s, by the mid-1920s, Smith, Ellington, Johnson and Waller usually received a portion of the take at these gatherings. After a couple of years, however, Duke backed off from the late night forays in order to spend more time composing. In later years, Ellington would honor Smith with his famous Portrait of the Lion, such was Willie's influence on him. Smith would return the favor a few years later with his Portrait of the Duke.

One incident which was less of a cutting contest than it was a humiliation occurred around 1928 when another big ego came to town - that of Ferdinand "Jelly Roll" Morton. After plying his best stuff at the Rhythm Club, including [allegedly] Morton's own Finger Breaker, Willie called Morton "Mr. One Hand." It was widely known that Smith had no affection for Morton. A similar incident is portrayed in the captivating Italian motion picture from 2000, Legend of 1900. Soon after, as the 1920s were reaching their giddy climax and eventual fall, Willie landed a gig at the Catagonia Club, one of some 30,000 speakeasies in the city by 1929, which is where many future swing and jazz artists heard him, including clarinetist Artie Shaw, who he nicknamed "Snow White," and the Dorsey Brothers. He even wrote a song for the place titled The Stuff is Here and It's Mellow. Willie fostered Shaw's interest and also played with him at The Nest and down on 52nd Street at Helbocks. (Shaw remembered this fondly as his first true lessons on how to swing, although he ended up leaving the music business after finding celebrity to be an unenjoyable aspect of performance.) The very tall Smith was hard to ignore, perched up high with his trademark bowler hat, and bragging more with his hands than with his mouth, which usually held a cigar in it.

As of the 1930 census, Willie was living St. Nicholas Avenue in North Harlem right around Sugar Hill. He was listed as an orchestra musician, referring to the ensembles he was playing and recording with that year. By the time the Great Depression settled in during the early 1930s, Smith still had little problem finding work locally, but also ventured out from time to time. One trip was with black actress Mae McKinney through a circuit of black theaters and riverboats in the American South.

Coming as he did from Newark, Willie saw a very different treatment of blacks in the South than he was accustomed too, and after that trip vowed to never again venture across the Mason Dixon Line. Things were changing musically in New York with the progression of jazz, even at the height of stride, with newcomers like Cab Calloway and Art Tatum. It is reported that Smith actually uncharacteristically declined to perform directly after the articulate and dynamic blind pianist after hearing him play for the first time.

|

The repeal of prohibition in 1933 helped to revitalize the nightclub scene, which in essence just meant opening the doors of the speakeasies to the general public, which benefited all of the Harlem pianists. Willie was also experimenting more with composition, calling upon his knowledge of impressionist works that he learned in his youth and beyond. With the help of Professor Hans Stenke and Clarence Williams' publishing house, he refined and published many of his original works in the mid-1930s, the longest lasting of these being Echo of Spring (or Echoes of Spring).

Solo recordings of them were soon to follow. Gershwin helped to further legitimize black music with the premiere of his opera Porgy and Bess in 1935. Smith also went in more of a jazz direction in performance, but always tempered with stride. He did five sessions of recordings with his group Willie Smith and His Cubs for Decca in 1935 and 1937, putting out some of the most balance stride renditions of the 1930s. Smith worked with white artist Mezz Mezzrow on record in 1936, making that ensemble one of the first popular integrated groups to do so, around the same time that Benny Goodman was recording with Teddy Wilson and Lionel Hampton. Smith also recorded in 1938 with the Milt Herth Trio and performed at the massive Carnival of Swing at Randall's Island, attended by some 25,000 people of all races. At the same time, people of his own faith were being harassed and rounded up in Germany and being Jewish was taking on a new level of meaning.

As things deteriorated in Europe, Smith continued to move forward, recording some of his most significant tracks in 1939 including eight of his own compositions for Commodore Records, run by a local record shop owner in Manhattan, Milt Gabler. Gabler was adamant about the power of small ensembles in contrast to the big swing bands which were reigning at that time, and went to great lengths to make certain his recordings would as technically superior as was possible, given the technology of the time. He ultimately released fourteen cuts featuring Willie on the piano, and another two of him with Joe Bushkin, even joined on one cut by Jess Stacy, both pianists white and at one or another time with the Goodman Band. The following year, 1940, had him working with Big Joe Turner, but he was also pained to find out his friend James P. had suffered a stroke which would temporarily incapacitate him for some time. In 1942, Willie finally gained admission into ASCAP. Then in October 1944 he was one of the features at a Carnegie Hall jazz concert along with a number of swing performers. As the 1940s progressed, Smith was finding his music was less in favor, as many of the Harlemites were gravitating towards the newer sounds of Dizzy Gillespie, Coleman Hawkins and Charlie Parker, the primary founders of the Be-Bop genre. Tatum was also a threat, as was the revolutionary approach of Thelonius Monk.

Gabler was adamant about the power of small ensembles in contrast to the big swing bands which were reigning at that time, and went to great lengths to make certain his recordings would as technically superior as was possible, given the technology of the time. He ultimately released fourteen cuts featuring Willie on the piano, and another two of him with Joe Bushkin, even joined on one cut by Jess Stacy, both pianists white and at one or another time with the Goodman Band. The following year, 1940, had him working with Big Joe Turner, but he was also pained to find out his friend James P. had suffered a stroke which would temporarily incapacitate him for some time. In 1942, Willie finally gained admission into ASCAP. Then in October 1944 he was one of the features at a Carnegie Hall jazz concert along with a number of swing performers. As the 1940s progressed, Smith was finding his music was less in favor, as many of the Harlemites were gravitating towards the newer sounds of Dizzy Gillespie, Coleman Hawkins and Charlie Parker, the primary founders of the Be-Bop genre. Tatum was also a threat, as was the revolutionary approach of Thelonius Monk.

Gabler was adamant about the power of small ensembles in contrast to the big swing bands which were reigning at that time, and went to great lengths to make certain his recordings would as technically superior as was possible, given the technology of the time. He ultimately released fourteen cuts featuring Willie on the piano, and another two of him with Joe Bushkin, even joined on one cut by Jess Stacy, both pianists white and at one or another time with the Goodman Band. The following year, 1940, had him working with Big Joe Turner, but he was also pained to find out his friend James P. had suffered a stroke which would temporarily incapacitate him for some time. In 1942, Willie finally gained admission into ASCAP. Then in October 1944 he was one of the features at a Carnegie Hall jazz concert along with a number of swing performers. As the 1940s progressed, Smith was finding his music was less in favor, as many of the Harlemites were gravitating towards the newer sounds of Dizzy Gillespie, Coleman Hawkins and Charlie Parker, the primary founders of the Be-Bop genre. Tatum was also a threat, as was the revolutionary approach of Thelonius Monk.

Gabler was adamant about the power of small ensembles in contrast to the big swing bands which were reigning at that time, and went to great lengths to make certain his recordings would as technically superior as was possible, given the technology of the time. He ultimately released fourteen cuts featuring Willie on the piano, and another two of him with Joe Bushkin, even joined on one cut by Jess Stacy, both pianists white and at one or another time with the Goodman Band. The following year, 1940, had him working with Big Joe Turner, but he was also pained to find out his friend James P. had suffered a stroke which would temporarily incapacitate him for some time. In 1942, Willie finally gained admission into ASCAP. Then in October 1944 he was one of the features at a Carnegie Hall jazz concert along with a number of swing performers. As the 1940s progressed, Smith was finding his music was less in favor, as many of the Harlemites were gravitating towards the newer sounds of Dizzy Gillespie, Coleman Hawkins and Charlie Parker, the primary founders of the Be-Bop genre. Tatum was also a threat, as was the revolutionary approach of Thelonius Monk.Already known for his flamboyant bravado and cigar chomping, Smith, unlike his friend Luckey Roberts, regularly imbibed to the point of outright drunkenness, and some of the episodes were quite memorable to others. He even admitted that his left hand was well developed because he needed his right hand for drinking. "If all the Sixth avenue subway conductors didn't know The Lion and where to dump him off, he never would have gotten home nights." However, he pulled back after one disturbing incident. One night while riding the subway in a partial stupor, Smith came to long enough to see "some bum" switching shoes with him.

Smith became increasingly frustrated with having to play with big bands just to have a gig, and with the general reactions of the younger crowds in noisy night spots. He suffered yet another personal loss in December 1943 when his long-time friend, Fats Waller, died of complications from pneumonia near Kansas City while on a train headed back to New York from Los Angeles.

Willie's mother died soon after in Newark in 1944. Wanting to find peace and further immerse himself in his faith, Smith became a cantor for a Harlem synagogue. During that period his professional card was printed mostly in Hebrew, save for "Willie 'The Lion' Smith, Greatest Piano Player in the World."

In his autobiography, Smith said that, "A lot of people are unable to understand my wanting to be Jewish. One said to me, 'Lion, you stepped up to the plate with one strike against you — and now you take a second one right down the middle!' They can't seem to realize I have a Jewish soul and belong to that faith." Soon after the war was over, Be-Bop took over Harlem, and Smith was considered a relic by many. He started suffering some health problems as well, so needed to slow down a bit, another frustration. Among his maladies were high blood pressure, dental infections and other complications that caused him to lose around 25 pounds in 1946. By the late 1940s he was teaching his craft more than performing, and spent more time with his duties as cantor.

|

On a trip to Europe in 1949 The Lion found out that he had many more fans there than he knew. Glad to be reunited with Paris once again, Smith made a series of recordings and concert appearances starting in early December 1949, and toured and played in other parts of Europe as well through February 1950, always enthusiastically received. This gave him a new confidence that would be duly rewarded once he returned back to the United States at the beginning of convergence of technology and nostalgia. He was back in Sugar Hill, Harlem, for the April census in 1950, listed as a piano player in a band. However, there is an additional surprise in that census, previously unknown to many. Living with him was a woman named Blanch… Blanch Smith. Piano player with a band. That had been her profession since the 1920s, largely in New Jersey, but often in Manhattan. They showed as married, even though she had claimed she was divorced in 1940. Other than marking her as a Negro in the record, the other data matches his white wife from the late 1910s. Add in that Blanche had been living but a few blocks away in the 1940s on Saint Nicholas Terrace, and that black people named Blanche were not all that commonly located, there is a very good chance she is one and the same.

Having had some fits and starts in San Francisco in early 1940s, the revival of ragtime and old-time styles in the early 1950s, largely spearheaded in the beginning by Capitol Records and artist Lou Busch, brought new hope to Willie, and new fame as well. He then became somewhat of a celebrity as a result of the book They All Played Ragtime and with his health improving decided to tour once again throughout the United States and back to Europe. Over the next two decades he, along with Eubie Blake and younger players such as Max Morath, Johnny Maddox and Robert Darch, would help to revitalize historical interest in the piano styles of the early part of the twentieth century. There were many jazz devotees who were aware of the impact Willie had thrust upon the music, and they held an event in Smith's honor, as reported in the New York Times of November 26, 1956:

Friends and admirers of Willie (The Lion) Smith, an influential and individualistic jazz pianist who has found a more appreciative audience among his fellow musicians than in the public at large, paid tribute to him last night. The occasion was a Dixieland concert at the Central Plaza, 111 Second Avenue, which marked his fortieth year in music.

Prominent in the long parade of leading Dixieland musicians who appeared on the bandstand during the evening was one leading representative of a different school of jazz, Dizzy Gillespie.

"If it hadn't been for the Lion and James P. Johnson and Fats Waller, we'd all have been floundering," said Mr. Gillespie, referring to the leading exponents of a jazz piano style favored in Harlem in the Nineteen Twenties.

One week later Smith was again part of the featured entertainment, returning to Carnegie Hall for an evening feted as "A Dixie Holiday." As reported in the New York Times on December 31, 1956, the highlights of that evening were New Orleans ragtime and jazz clarinetist Tony Parenti, who had appeared with Willie earlier that year, trumpeter Max Kaminsky, and Willie himself. He "created a precedent for Carnegie Hall by chewing a cigar not only while he played the piano but even when he was singing. Mr. Smith appeared briefly playing his lyrically impressionistic composition, 'Echo of Spring,' and demonstrating his vigorous skill in the 'stride' piano style that first brought him to attention in the early Nineteen Twenties." There was still much more to come.

the highlights of that evening were New Orleans ragtime and jazz clarinetist Tony Parenti, who had appeared with Willie earlier that year, trumpeter Max Kaminsky, and Willie himself. He "created a precedent for Carnegie Hall by chewing a cigar not only while he played the piano but even when he was singing. Mr. Smith appeared briefly playing his lyrically impressionistic composition, 'Echo of Spring,' and demonstrating his vigorous skill in the 'stride' piano style that first brought him to attention in the early Nineteen Twenties." There was still much more to come.

the highlights of that evening were New Orleans ragtime and jazz clarinetist Tony Parenti, who had appeared with Willie earlier that year, trumpeter Max Kaminsky, and Willie himself. He "created a precedent for Carnegie Hall by chewing a cigar not only while he played the piano but even when he was singing. Mr. Smith appeared briefly playing his lyrically impressionistic composition, 'Echo of Spring,' and demonstrating his vigorous skill in the 'stride' piano style that first brought him to attention in the early Nineteen Twenties." There was still much more to come.

the highlights of that evening were New Orleans ragtime and jazz clarinetist Tony Parenti, who had appeared with Willie earlier that year, trumpeter Max Kaminsky, and Willie himself. He "created a precedent for Carnegie Hall by chewing a cigar not only while he played the piano but even when he was singing. Mr. Smith appeared briefly playing his lyrically impressionistic composition, 'Echo of Spring,' and demonstrating his vigorous skill in the 'stride' piano style that first brought him to attention in the early Nineteen Twenties." There was still much more to come.As his fame was once again on the rise, Willie was also almost part of a very historical photograph. In the summer 1958, photographer Art Kane was hired by Esquire magazine to provide a photograph for an article about jazz. He managed to gather nearly 60 musicians in Harlem for a series of photographs taken on the morning of August 12 on 126th Street. Among them were current jazz greats, stride pianists of the 1940s, and two pioneers, Willie and Luckey Roberts. Kane took many combinations of photographs that morning, including one of Roberts and Smith together. By the time the official portrait for the article was taken, the sweltering August heat had gotten to Willie. He could no longer stand, so was sitting nearby when some of the final shots were taken, thus just missing being memorialized in Esquire. In 2004, director Steven Spielberg shot the film The Terminal, centered around an Eastern European visitor to New York who was trying to obtain one final autograph to accompany a copy of that photograph, sans "The Lion."

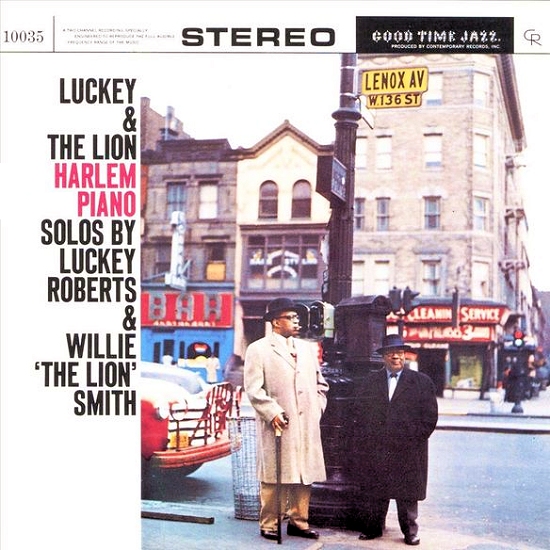

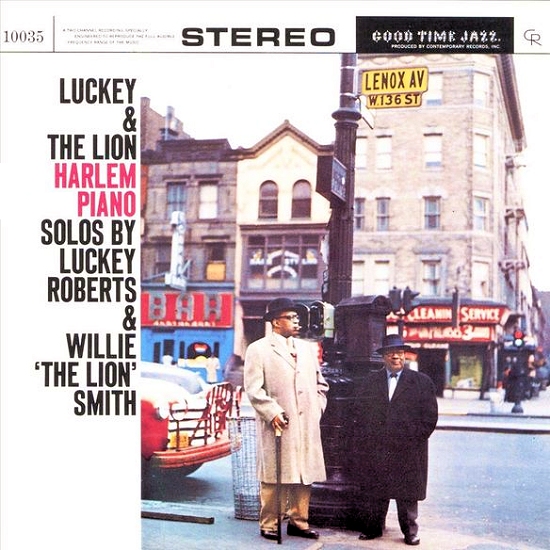

Smith appeared often on television variety and talk shows, sometimes with his companions from the height of Harlem stride piano days. He was recorded more often as well, including a notable Good Time Jazz stereo session opposite his old friend Roberts recorded in March 1958 in New York City by Lester Koenig. In 1964, with the help of George Hoefer, Willie published his autobiography, Music on My Mind, with a long introduction by his admirer Duke Ellington. It contains many questionable passages in terms of time line and accuracy, but is still an engrossing look into New Jersey and New York of the early 20th century. Years later in 1969 he even performed a couple of recorded solo sessions at the trendy Blues Alley in Washington DC, which were captured by Hank O'Neal and released on two albums by independent Chiaroscuro Records. But he had to slow down in the early 1970s.

It contains many questionable passages in terms of time line and accuracy, but is still an engrossing look into New Jersey and New York of the early 20th century. Years later in 1969 he even performed a couple of recorded solo sessions at the trendy Blues Alley in Washington DC, which were captured by Hank O'Neal and released on two albums by independent Chiaroscuro Records. But he had to slow down in the early 1970s.

It contains many questionable passages in terms of time line and accuracy, but is still an engrossing look into New Jersey and New York of the early 20th century. Years later in 1969 he even performed a couple of recorded solo sessions at the trendy Blues Alley in Washington DC, which were captured by Hank O'Neal and released on two albums by independent Chiaroscuro Records. But he had to slow down in the early 1970s.

It contains many questionable passages in terms of time line and accuracy, but is still an engrossing look into New Jersey and New York of the early 20th century. Years later in 1969 he even performed a couple of recorded solo sessions at the trendy Blues Alley in Washington DC, which were captured by Hank O'Neal and released on two albums by independent Chiaroscuro Records. But he had to slow down in the early 1970s.He still did the occasional special event, usually playing along with other great artists of both contemporary and classic vintage. Willie was one of the features at the 18th Annual Newport Jazz Festival in 1971, along with Eubie, Ellington, Charlie Mingus, Stan Kenton's dynamic group and the Buddy Rich Orchestra. He also introduced his protégé Mike Lipskin, who would become one of the major biographers and keepers of the Smith legacy. Willie was still quite full of strong opinions, and when queried about some of the performances he had heard he replied, "Buddy tore the place down last night. Stan's band was too much reading music. Jazz is from the heart and soul. And Duke's men weren't together. If Duke hadn't been so well known he'd have laid an egg." Willie himself laid no eggs in Newport, appearing again at the 19th Annual event in 1972.

Another 1972 performance of note was a ragtime concert held at the Whitney Museum in New York, where he appeared with Eubie, Earl "Fatha" Hines, Max Morath and newcomer William Bolcom. "Willie (The Lion) Smith, in red vest, black derby and jaunty cigar (for which an ashtray was hastily rushed out to the piano) offered a sampling of lilting, melodic style." It may or may not have been a frustration to the aging pianist, but his friend Eubie was clearly the star of the event. "The audience, predominantly young and knowledgeable, stood and filled the Whitney's second-floor gallery with its cheers before Mr. Blake was finally allowed to leave."

Smith's last known recording session was in Paris in 1972. In April 1973, Smith was admitted to New York University Hospital in poor health. Willie "The Lion" Smith left the building at age 80, moving on to other gigs in another place, but fortunately leaving behind a legacy of influence, compositions and recordings for us to enjoy in perpetuity. He was fondly remembered on his death in a short feature in the New York Times printed on April 21, 1973:

In every art form there are those signal talents whose influence pervades all the rest, whether acknowledged or not. In jazz piano, this was true of the late James P. Johnson and his contemporary, Willie "The Lion" Smith. The Lion's eight decades touched the world of jazz in its every chord, melody and rhythm. "No one could ever play the same again after once hearing The Lion," says one of his most illustrious and grateful students, Duke Ellington. Armed with his ubiquitous black derby and cigar, The Lion rode atop American music from the start in the sportin' house to the serious contribution to world culture which it has now become.

Alternately cantankerous and ebullient, just like his music, Willie always proved that he was in command of the show. The touch of the fingers of his rolling left hand brought an instant authority that no amount of today's electronic amplification can convey. Now the show will go on without him, but forever enriched for having had him there. In the Duke's words, "he was the master of us all."

Many of his recordings which had never or rarely been heard began to surface in the wake of his death, and many more have since been restored onto CD releases, allowing a aural glimpse into a colorful past that is long gone. His performances certainly create a yearning in many listeners to be back at one of those late night rent parties just to see and hear James P., Fats and Willie in their element. Long Live the Lion.

In spite of the detail, this is really only an overview of Smith's life, peripheral to ragtime in many respects. Some of the recently uncovered information was put forward by the late Mike Meddings on his extraordinary site, www.doctorjazz.co.uk. The bulk of this biography comes from public records, periodicals, newspapers, his somewhat usefuul autobiography Music On My Mind, and interviews from the Mark Fields and Mike Lipskin documentary on his life produced by APT.

Compositions

Compositions