Jack Mills was one of the most important publishers of the 1920s in that he kept ragtime, or at the very least the spirit and concept of it, alive in a time when it had all but been declared dead. He was not afraid to mix simple popular songs with rearranged classical works and extremely difficult novelty ragtime pieces all within his vast catalog. Little was known of his origins before 1919, the same case with his brother Irving Mills, but our initial research in 2008 found at least something about the early years of this ambitious publisher and his musical brother.

Jack and Irving were the children of hat maker Hyman [Chaim] Minsky (b.1867) and his bride Sophia Schifre (b.1869) from Odessa, Russia. Jack was born in Odessa in 1891 as Jacob Minsky and his younger brother Irving as Isadore [or Isaac] Minsky in 1894, also in Odessa. There are claims that Irving was born in New York City, but official government records, information given by himself, and the family time line indicate otherwise. The Minsky family migrated to the United States, arriving in New York on July 25, 1896, and settled in Manhattan, New York. They were shown in the 1900 enumeration as living on Essex Street. On January 20, 1903, Hyman was naturalized as a United States citizen, the only one in his family at that time. He died of tuberculosis on April 5, 1905, leaving Sophia and the boys to fend for themselves. Jacob was barely in his teens as he and Isadore hit the streets looking for odd jobs. They did everything from menial work in restaurants to selling items in the garment district, even selling wallpaper at one point. The 1910 census showed that Isadore had by now anglicized his name to Irving, but the family still retained Minsky as their last name. Jacob was a packer in a hat store and Irving was a telephone operator.

In the early 1910s Irving got a job working as a page boy at Shanley's Restaurant near the theater district, which at that time was at Broadway and 29th, several blocks south of where it would centered. before the decade was out. Jacob also started working in the same area as a pianist (possibly a singer) and was exposed to some of the great show writers and performers. Irving soon was working for the Friars as a page boy where many of the stars of the time hung out. However, they usually did not perform in this venue, so he ended up getting a job at Proctor's theater where he could be closer to the action. Jacob ended up working within a few blocks as a song plugger for some of the Tin Pan Alley firms, possibly more than one at a time. There are reports that the family moved to Philadelphia at this time, but this does not align with official records, which show them relatively consistently in New York City. However, Irving and his mother may have moved or at least stayed there for a while in the early 1910s, perhaps a long term visit to relations.

Jacob also started working in the same area as a pianist (possibly a singer) and was exposed to some of the great show writers and performers. Irving soon was working for the Friars as a page boy where many of the stars of the time hung out. However, they usually did not perform in this venue, so he ended up getting a job at Proctor's theater where he could be closer to the action. Jacob ended up working within a few blocks as a song plugger for some of the Tin Pan Alley firms, possibly more than one at a time. There are reports that the family moved to Philadelphia at this time, but this does not align with official records, which show them relatively consistently in New York City. However, Irving and his mother may have moved or at least stayed there for a while in the early 1910s, perhaps a long term visit to relations.

Jacob also started working in the same area as a pianist (possibly a singer) and was exposed to some of the great show writers and performers. Irving soon was working for the Friars as a page boy where many of the stars of the time hung out. However, they usually did not perform in this venue, so he ended up getting a job at Proctor's theater where he could be closer to the action. Jacob ended up working within a few blocks as a song plugger for some of the Tin Pan Alley firms, possibly more than one at a time. There are reports that the family moved to Philadelphia at this time, but this does not align with official records, which show them relatively consistently in New York City. However, Irving and his mother may have moved or at least stayed there for a while in the early 1910s, perhaps a long term visit to relations.

Jacob also started working in the same area as a pianist (possibly a singer) and was exposed to some of the great show writers and performers. Irving soon was working for the Friars as a page boy where many of the stars of the time hung out. However, they usually did not perform in this venue, so he ended up getting a job at Proctor's theater where he could be closer to the action. Jacob ended up working within a few blocks as a song plugger for some of the Tin Pan Alley firms, possibly more than one at a time. There are reports that the family moved to Philadelphia at this time, but this does not align with official records, which show them relatively consistently in New York City. However, Irving and his mother may have moved or at least stayed there for a while in the early 1910s, perhaps a long term visit to relations.Irving found his own success as a song plugger, working at Snellenburg's Department Store by day, then doubling at night as a plugger for publisher Emmet Welsh leading singalongs in theaters. He met his wife Elizabeth "Bessie" Wiliensky in 1913 in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, where he was working for Welsh, and proposed marriage to her after only one week. The couple eventually relocated to Philadelphia. But Jacob likely remained in New York City during this period, and is shown in at least one city directory in the mid 1910s. His 1918 draft card shows him working for Broadway Music which was run at that time by Will and Albert Von Tilzer. It is not known when he anglicized his last name, but 'Mills' is shown as an alternate name in parenthesis next to Jacob Minsky. Irving's draft record shows him working as a "gent's furnishings" salesman and living in Brooklyn. Both brothers show as having been naturalized as United States citizens by this time.

By late 1918 Jacob had earned the position of a manager for the publishing house of McCarthy and Fisher, run by Joe McCarthy and Fred Fisher. He was likely very good at his work since he was awarded a cash bonus in the Spring of 1919, one of the largest he had ever received to date. It did not take long for Jacob and Irving, the latter who had been working for Leo Feist in Philadelphia, to pool their experiences and their desire for business independence. They decided to open their own firm, an enterprise funded in part by Jacob's now former employers. So it was in July of 1919 that Jack Mills Music opened for business with Jacob as the namesake president and Irving, as he now called himself, as his vice president and secondary manager in Philadelphia. With a print jobber available to Jack, and with his knowledge about distribution and advertising, he only lacked one thing at this point - content. So Jack Mills became a songwriter for the very short term. In the end, it would be evident that Irving was the composer in the family, but Jack needed something out there so he dashed off a couple of pieces. One was the forgettable I Don't Want a Doctor (All I Want is a Beautiful Girl). The second was the slightly awkward I'll Buy The Ring (And Change Your Name to Mine) with lyricists Ed Rose and Willam Raskin. Neither was a great seller, but at some point in the 1920s comedian George Burns picked up on Buy the Ring and it became one of his standard crooning pieces for the rest of his life, having also been recorded on a minstrel show record in the 1950s and in a television special with singer John Denver in the 1970s. But that was in the future, and Jack Mills had to focus on the present.

having also been recorded on a minstrel show record in the 1950s and in a television special with singer John Denver in the 1970s. But that was in the future, and Jack Mills had to focus on the present.

having also been recorded on a minstrel show record in the 1950s and in a television special with singer John Denver in the 1970s. But that was in the future, and Jack Mills had to focus on the present.

having also been recorded on a minstrel show record in the 1950s and in a television special with singer John Denver in the 1970s. But that was in the future, and Jack Mills had to focus on the present.There were a number of composers looking for a different outlet, or even any outlet in the post-war frenzy of Tin Pan Alley, and Jack courted them successfully. Yet there was no real focus for the company in 1919 and 1920 other than putting out a few dance tunes or novelty songs. It took a death, however, to bring the Mills firm to life. That was the death of the famed opera singer Enrico Caruso who had survived many calamities such as the San Francisco earthquake of 1906 and numerous hazardous ocean crossings, but was ultimately taken down by a burst abscess. Mills published They Needed a Song Bird in Heaven (So God Took Caruso Away), and it was just the antidote for a grieving public, as well as for the fledgling firm. The sales from this got Mills noticed, and proving his ability to market and distribute he was able to lure in more big names. For his part, Irving became a sort of scout for the firm, seeking out new talent and convincing them to publish with the company. One of the coups the brothers scored in 1921 was the induction of black songwriters Henry Creamer and J. Turner Layton into their catalog, which not only gave them substantive pieces to print, but also sparked the interest of many other talented black composers who may have had difficulty getting published up through this time. From that point on, Irving had little trouble pulling more of them into the fold. As of the 1920 census Irving was still living in Philadelphia and listed himself as a music salesman. Along with his wife they had produced four children in five years, including Beatrice (1914), Sidney (1915), Jack (1916) and Florence (1919). Jack, still officially listed as Jacob, was living with his mother Sophia in Manhattan at a Madison Avenue address.

There was a need for good songwriters of any color, and one of the first to join as a staff pianist was Jimmy McHugh, who had abandoned Boston for Manhattan in order to get a jump start on his music career. He was a talented pianist who had been working as a song plugger in Boston, and if he could sell songs there the Mills brothers figured he could certainly sell them in New York. So they hired him as a professional manager to help with promotion, and in short order he promoted himself as well, adding several fine numbers to the catalog from the start. McHugh became a staple of the Jack Mills catalog in the coming years, but there was another name looming on the horizon which would provide the hook that Jack Mills was looking for to set his firm apart from the others. It was a combination of old and new, and the resurrection of old ragtime in a new guise would be the catalyst for the company's growth in the 1920s.

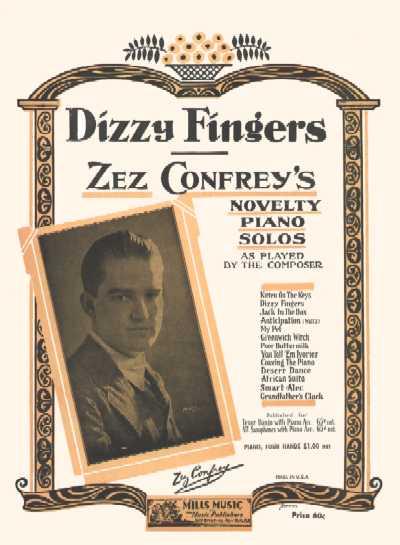

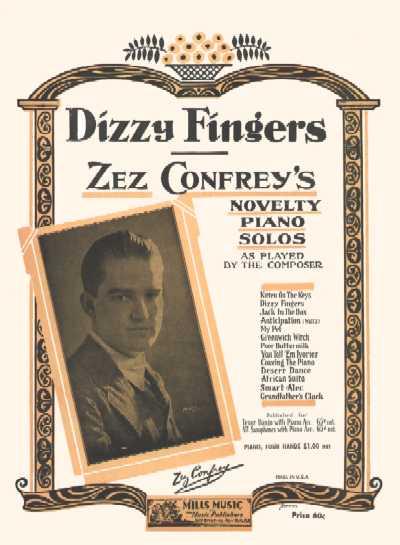

A gifted musician from Chicago, who had been arranging and playing piano rolls for QRS for several years, was having trouble convincing them to take his own compositions - perhaps in part because he did not have a publisher. Three of them did make it to piano roll in 1918 and sold fairly well, but that still did not replace the effectiveness of having them in print. Virtually any firm he took his work to rejected it because it was too complex for the average consumer to even approach. So it was that Edward Elzear "Zez" Confrey made his way to New York and tried again to push his product on the newer publishing house in town, Jack Mills Music. Mills did not demur, realizing that it's not always the destination, but sometimes the journey which is worth the experience. Seeing that Confrey's works were largely made up of patterns that could be mastered with a little work, he saw the potential in the genre that until this time had largely existed on piano rolls, and took a chance on the pieces. In conjunction with the printing of My Pet and the benchmark Kitten on the Keys, Confrey also made recordings of the works, and they became among the first available in roll, recorded and printed form, all directly from the composer. Despite the difficulty of the pieces, or perhaps even because of the challenge, Kitten on the Keys became a top seller around the United States, and the recordings sold the music, and the music sold the recordings. Over 1 million copies (reportedly) of the sheets and 100,000 of the records of KOTK got into the hands of consumers within a year. While this was not the first piece of the genre of Novelty Ragtime, it was among the best known and Mills soon thrived on a series of pieces in the same vein by Confrey and other composers.

Three of them did make it to piano roll in 1918 and sold fairly well, but that still did not replace the effectiveness of having them in print. Virtually any firm he took his work to rejected it because it was too complex for the average consumer to even approach. So it was that Edward Elzear "Zez" Confrey made his way to New York and tried again to push his product on the newer publishing house in town, Jack Mills Music. Mills did not demur, realizing that it's not always the destination, but sometimes the journey which is worth the experience. Seeing that Confrey's works were largely made up of patterns that could be mastered with a little work, he saw the potential in the genre that until this time had largely existed on piano rolls, and took a chance on the pieces. In conjunction with the printing of My Pet and the benchmark Kitten on the Keys, Confrey also made recordings of the works, and they became among the first available in roll, recorded and printed form, all directly from the composer. Despite the difficulty of the pieces, or perhaps even because of the challenge, Kitten on the Keys became a top seller around the United States, and the recordings sold the music, and the music sold the recordings. Over 1 million copies (reportedly) of the sheets and 100,000 of the records of KOTK got into the hands of consumers within a year. While this was not the first piece of the genre of Novelty Ragtime, it was among the best known and Mills soon thrived on a series of pieces in the same vein by Confrey and other composers.

Three of them did make it to piano roll in 1918 and sold fairly well, but that still did not replace the effectiveness of having them in print. Virtually any firm he took his work to rejected it because it was too complex for the average consumer to even approach. So it was that Edward Elzear "Zez" Confrey made his way to New York and tried again to push his product on the newer publishing house in town, Jack Mills Music. Mills did not demur, realizing that it's not always the destination, but sometimes the journey which is worth the experience. Seeing that Confrey's works were largely made up of patterns that could be mastered with a little work, he saw the potential in the genre that until this time had largely existed on piano rolls, and took a chance on the pieces. In conjunction with the printing of My Pet and the benchmark Kitten on the Keys, Confrey also made recordings of the works, and they became among the first available in roll, recorded and printed form, all directly from the composer. Despite the difficulty of the pieces, or perhaps even because of the challenge, Kitten on the Keys became a top seller around the United States, and the recordings sold the music, and the music sold the recordings. Over 1 million copies (reportedly) of the sheets and 100,000 of the records of KOTK got into the hands of consumers within a year. While this was not the first piece of the genre of Novelty Ragtime, it was among the best known and Mills soon thrived on a series of pieces in the same vein by Confrey and other composers.

Three of them did make it to piano roll in 1918 and sold fairly well, but that still did not replace the effectiveness of having them in print. Virtually any firm he took his work to rejected it because it was too complex for the average consumer to even approach. So it was that Edward Elzear "Zez" Confrey made his way to New York and tried again to push his product on the newer publishing house in town, Jack Mills Music. Mills did not demur, realizing that it's not always the destination, but sometimes the journey which is worth the experience. Seeing that Confrey's works were largely made up of patterns that could be mastered with a little work, he saw the potential in the genre that until this time had largely existed on piano rolls, and took a chance on the pieces. In conjunction with the printing of My Pet and the benchmark Kitten on the Keys, Confrey also made recordings of the works, and they became among the first available in roll, recorded and printed form, all directly from the composer. Despite the difficulty of the pieces, or perhaps even because of the challenge, Kitten on the Keys became a top seller around the United States, and the recordings sold the music, and the music sold the recordings. Over 1 million copies (reportedly) of the sheets and 100,000 of the records of KOTK got into the hands of consumers within a year. While this was not the first piece of the genre of Novelty Ragtime, it was among the best known and Mills soon thrived on a series of pieces in the same vein by Confrey and other composers.Obviously the success of Confrey did not go unnoticed by his performing and composing peers, and they figured if Jack was interested in that type stuff they would also submit what they had to him. It seemed that no matter the difficulty of the piece, the sheer novelty of being one of the most famous publishers of novelty rags (even though he had considerable competition from Robbins Music) worked well for Mills, and he took on most comers. As early as 1923 it became evident that a method book for breaking down the concept of patterns in this pieces would also do well, and Confrey provided one that became the standard. Folios of his pieces also sold quite well, allowing players to purchase multiple compositions in one package. Others soon saw their "too hard to play but fun to learn" pieces issued by the firm, including Frank Banta, Rube Bloom, Arthur Schutt, and Max Kortlander (later a major part of QRS). In late June of 1924, Jack was married to Estelle Hager, who was born of Russian parents. He applied for a passport for their honeymoon to Europe, showing his birth name of Jacob Minsky, with destinations including Britain, France and Germany. Sailing on the Berengaria and returning on the Leviathan, there is some likelihood he was also engaged in establishing European contacts for his business as well.

Since ragtime appeared to still be selling, Mills acquired a number of works from the 1910s that were up for sale, many of which would show up in folios between the 1920s and 1960s. One of these included Scott Joplin's Magnetic Rag which actually appeared in a folio of novelty works, not fully in appropriate given its complexity. The company also acquired and rearranged a number of light classics as well, giving variety and breadth to the label, particularly when they were advertised on the back covers of popular works. To add even more to this wealth, early popular songs from the 19th century were also reissued in newer formats reflecting 1920s style. But with the input of Irving, Jack Mills provided a haven for black writers as well. Among them were Alberta Hunter, James P. Johnson and Thomas "Fats" Waller. Following the lead of record companies who often had a separate label for "colored music," Mills created Down South Music, and put Fletcher Henderson (who would later become the primary arranger of the pieces that made Benny Goodman famous) in charge. It was through those dealings that Mills was able to snag the hit Ain't Misbehavin' in 1929.

The company also acquired and rearranged a number of light classics as well, giving variety and breadth to the label, particularly when they were advertised on the back covers of popular works. To add even more to this wealth, early popular songs from the 19th century were also reissued in newer formats reflecting 1920s style. But with the input of Irving, Jack Mills provided a haven for black writers as well. Among them were Alberta Hunter, James P. Johnson and Thomas "Fats" Waller. Following the lead of record companies who often had a separate label for "colored music," Mills created Down South Music, and put Fletcher Henderson (who would later become the primary arranger of the pieces that made Benny Goodman famous) in charge. It was through those dealings that Mills was able to snag the hit Ain't Misbehavin' in 1929.

The company also acquired and rearranged a number of light classics as well, giving variety and breadth to the label, particularly when they were advertised on the back covers of popular works. To add even more to this wealth, early popular songs from the 19th century were also reissued in newer formats reflecting 1920s style. But with the input of Irving, Jack Mills provided a haven for black writers as well. Among them were Alberta Hunter, James P. Johnson and Thomas "Fats" Waller. Following the lead of record companies who often had a separate label for "colored music," Mills created Down South Music, and put Fletcher Henderson (who would later become the primary arranger of the pieces that made Benny Goodman famous) in charge. It was through those dealings that Mills was able to snag the hit Ain't Misbehavin' in 1929.

The company also acquired and rearranged a number of light classics as well, giving variety and breadth to the label, particularly when they were advertised on the back covers of popular works. To add even more to this wealth, early popular songs from the 19th century were also reissued in newer formats reflecting 1920s style. But with the input of Irving, Jack Mills provided a haven for black writers as well. Among them were Alberta Hunter, James P. Johnson and Thomas "Fats" Waller. Following the lead of record companies who often had a separate label for "colored music," Mills created Down South Music, and put Fletcher Henderson (who would later become the primary arranger of the pieces that made Benny Goodman famous) in charge. It was through those dealings that Mills was able to snag the hit Ain't Misbehavin' in 1929.Irving became an entrepreneur as well, forming dance bands out of the finest available musicians and recording them for discount record labels. He also would acquire the rights to many of their pieces for Jack Mills to publish. One important association was made around 1924 when Irving was in Washington, D.C., and scouting some of the talent there. After listening to one group in particular he abandoned any more stops for the evening and stayed to listen to everything they did. Thus it was that he invited Duke Ellington to be a part of Mills Music, providing an outlet for publishing the pieces the band was recording. Irving would end up managing Ellington's band for several years, arranging for some of his notable early recording sessions as well. His music was of such a high caliber that another firm, Gotham Music Service, was spun off in 1927 to handle Ellington's compositions and recording copyrights exclusively. While Irving's name shows up as a credit on some Ellington compositions, this does not mean he was materially involved in the writing of them, as this was a practice of many managers and even other star talent of the time as a way to signify their non-material contributions to a composer.

Another major coup was the signing of an eclectic writer who to many came off as a bit rough around the edges. After contributing the raggy jazz band hit Riverboat Shuffle in 1925 and Washboard Blues in 1926, Hoagy Carmichael justified his publisher's faith in 1929 with what many have called the number one standard of all time, Stardust. With a verse and a chorus, both have been performed as separate components or as a mix, one of the few pieces in history in which either section of the song is instantly recognizable. When words were added a few months later, they helped bring out another talent who had been working for Mills, lyricist Mitchell Parish who would work more magic with Carmichael. 1929 was a good year for Mills and company.

When words were added a few months later, they helped bring out another talent who had been working for Mills, lyricist Mitchell Parish who would work more magic with Carmichael. 1929 was a good year for Mills and company.

When words were added a few months later, they helped bring out another talent who had been working for Mills, lyricist Mitchell Parish who would work more magic with Carmichael. 1929 was a good year for Mills and company.

When words were added a few months later, they helped bring out another talent who had been working for Mills, lyricist Mitchell Parish who would work more magic with Carmichael. 1929 was a good year for Mills and company.Having changed the name to Mills Music in 1928, Jack further enhanced his catalog as the Great Depression set in, snatching up several medium-sized firms on Tin Pan Alley, including Vandersloot Music, McCarthy & Fisher and Gus Edwards Music. But his biggest grab came in 1931 when he acquired the entire catalog of Waterson, Berlin and Snyder for a mere $5,000. Irving Berlin's association with this firm was, by this time, in name only as he was doing very well with his own music company. But several of his ragtime pieces were now owned by Mills, who also ended up with Snyder's big hit The Sheik of Araby. As of 1930 Jack Mills was living well in Lawrence, Nassau County, New York, with Estelle, and now two children added to the fold, Helen (1926) and Martin (1928). Son Stanley would be born later in the year. Irving was living in Brooklyn with Bessie and had added three more children in the 1920s, Paul (1921), Robert (1922) and Warren (1924), for a total of seven. Both brothers listed themselves as music publishers that year.

At the height of the Great Depression, Mills Music moved into the new Brill Building in 1932. This would become a new center point for Tin Pan Alley songwriters, hosting a number of luminaries right into the 1960s, including Carole King and Neil Sedaka. In many ways, Mills, along with Irving Berlin, were among the last of the cadre of publishing firms that established music and entertainment as a bona fide business in the United States. While ragtime was by now a thing of the past, yet still kept alive in his catalog, Mills did manage to publish a number of stride pieces by guys who had their roots in ragtime, including Willie "The Lion" Smith and radio personality Bill Krenz ("the tallest ragtime pianist in captivity"). Two more subsidiaries appeared in the late 1930s, including American Academy of Music and Exclusive Publications. The Mills group became largely a purveyor of pop tunes in the 1940s and 1950s. As of the 1940 census, Irving was living in Manhattan with Bessie, Sidney, Florence, Paul and Warren, his occupation listed as music publisher. Jack was not readily found in that record despite deep searches. By 1950, empty nesters Irving and Bessie (as Essie) had relocated to Beverly Hills, California, where he was still listed as the proprietor of amusic publishing company. Jack, Estelle, and their three children was living large in Lawrence, a wealthy community on the southwest corner of Long Island, New York. He was listed as an executive in the music publishing industry, with Martin working as a field salesman for his dad.

The Mills group became largely a purveyor of pop tunes in the 1940s and 1950s. As of the 1940 census, Irving was living in Manhattan with Bessie, Sidney, Florence, Paul and Warren, his occupation listed as music publisher. Jack was not readily found in that record despite deep searches. By 1950, empty nesters Irving and Bessie (as Essie) had relocated to Beverly Hills, California, where he was still listed as the proprietor of amusic publishing company. Jack, Estelle, and their three children was living large in Lawrence, a wealthy community on the southwest corner of Long Island, New York. He was listed as an executive in the music publishing industry, with Martin working as a field salesman for his dad.

The Mills group became largely a purveyor of pop tunes in the 1940s and 1950s. As of the 1940 census, Irving was living in Manhattan with Bessie, Sidney, Florence, Paul and Warren, his occupation listed as music publisher. Jack was not readily found in that record despite deep searches. By 1950, empty nesters Irving and Bessie (as Essie) had relocated to Beverly Hills, California, where he was still listed as the proprietor of amusic publishing company. Jack, Estelle, and their three children was living large in Lawrence, a wealthy community on the southwest corner of Long Island, New York. He was listed as an executive in the music publishing industry, with Martin working as a field salesman for his dad.

The Mills group became largely a purveyor of pop tunes in the 1940s and 1950s. As of the 1940 census, Irving was living in Manhattan with Bessie, Sidney, Florence, Paul and Warren, his occupation listed as music publisher. Jack was not readily found in that record despite deep searches. By 1950, empty nesters Irving and Bessie (as Essie) had relocated to Beverly Hills, California, where he was still listed as the proprietor of amusic publishing company. Jack, Estelle, and their three children was living large in Lawrence, a wealthy community on the southwest corner of Long Island, New York. He was listed as an executive in the music publishing industry, with Martin working as a field salesman for his dad.In the wake of the popularity of Honky-Tonk piano in throughout the 1950s, Mills dug into his catalog and released at least three folios of ragtime era material in the early 1960s, including Play Them Rags and Ragtime Piano Solos. This was the first time in up to 50 years that many of these classics had been in print, and the folios sold well. More importantly, Mills Music was the recipient of a number of works composed from the 1910s to the late 1950s by composer Joseph F. Lamb who had recently passed on. In 1964 Mills brought out the very important folio Ragtime Treasures in conjunction with the third edition of the groundbreaking book They All Played Ragtime, and the folio sold well during its entire time in print through the early 1990s.

But Jack was pretty much done at this point. In 1965 he decided to cash in and retire, as did Irving. The Mills brothers sold their firm to the Utilities and Industries Company for $5 million. Much of the material now appeared under the name Belwin/Mills, acknowledging the role of the great entrepreneurs from Russia who made it big in American music, albeit behind the scenes. Jack retired to Hollywood, Florida, where he died in 1979. Irving ended up in Palm Springs, California, where he passed in 1985. Both of them had a significant impact on the musical landscape of the post-ragtime years, and it is possible that their efforts, along with Robbins, in keeping some form of the music in print after it was supposedly passé, helped to keep it alive after all.

Some of the narrative of Jack Mills's business life was derived from the extraordinary efforts of Dave Jasen and later Gene Jones in the books Tin Pan Alley and That American Rag. They are highly recommended sources for a very different look at how the music was composed and popularized and how it eventually reached the public. Information on Irving Mills came in part from the writings of his son Robert Mills. Thanks also go to Robert Harwood, author of I Went Down to St. James Infirmary which includes some information on the Mills, for a couple of important corrections that sent me back to the original sources for clarification.

The remaining information including the discovery of the names and locations of Jack and Irving Mills before 1920 were through research by the author. If anybody wants to follow up further with these finds as Mr. Harwood has, please contact us if you want to share notes on the Minskys/Mills.

Published Composers

Published Composers