John Stepan Zamecnik (pronounced zam-ish-nick) was a first generation American born in Ohio of Bohemian (now Czech Republic) parents Josef "Joseph" Zamecnik and Catherine "Kate" Hrubecky. His parents arrived in New York on May 26, 1870 with his older sisters Catherine and Anna. John was one of three children in the family that survived to adulthood. His father was an accomplished musician, and saw this propensity in his son, so made sure he was musically trained early on in his youth.  In the 1880 census Joseph the family was living in Cleveland with Joseph working as both a musician and a barrel cooper. Interestingly enough, they were living in a home on Croton Street next door to a music teacher, Mr. A.J. Rock.

In the 1880 census Joseph the family was living in Cleveland with Joseph working as both a musician and a barrel cooper. Interestingly enough, they were living in a home on Croton Street next door to a music teacher, Mr. A.J. Rock.

In the 1880 census Joseph the family was living in Cleveland with Joseph working as both a musician and a barrel cooper. Interestingly enough, they were living in a home on Croton Street next door to a music teacher, Mr. A.J. Rock.

In the 1880 census Joseph the family was living in Cleveland with Joseph working as both a musician and a barrel cooper. Interestingly enough, they were living in a home on Croton Street next door to a music teacher, Mr. A.J. Rock. At age 15, John took courses in harmony and theory. At 18 he was sent to the Prague Conservatory of Music to study all facets of music. This included a composition class with famed composer Anton Dvořák. After four years John returned to the US, and is listed in the 1900 census, still in Cleveland, as a musician living in his parent's home, and his father also listed in the same profession at age 68. The following year John was working as first violinist with the Pittsburgh Symphony, which at that time was under the direction of operetta and song composer Victor Herbert. He spent three years in Pittsburgh before returning home to Ohio.

Back in Cleveland, John married Mary Barbara Hodous in 1904, and they soon had two sons, Walter and Edwin. It is unclear what musical activities he was involved with at that time, perhaps working on composing and playing with local groups, but in 1908 he became the musical director for the new Cleveland Hippodrome. This gave him a chance to have some of his compositions for stage and orchestra performed, and once they started showing movies, he quickly adapted to this by writing appropriate music that could be interchanged between films with similar scenarios. This would soon become his primary genre, and one that would influence cinema for quite some time.

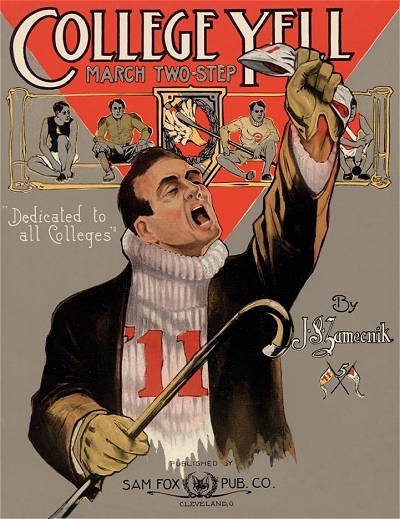

In 1908 Zamecnik's first published piece with Sam Fox, College Yell March, began a long relationship with the Cleveland publisher that made him a force in the publishing industry in spite of his non-metropolitan area location in northern Ohio. Some of the early pieces included syncopated marches, waltzes, and good popular tunes, yet with something more. Fox saw in Zamecnik a musical resource that was obviously well-versed in classical writing and performance, yet did not put down popular styles, even embracing them to a degree. Indeed, the composer became as known for his popular works as his semi-classical ones.  A typical notice was found in the trade magazines in 1916: "A most timely publication is 'All America,' a brilliant march by J. S. Zamecnik and one of the features of the Sam Fox Co.'s catalog. The piece has a martial swing to it and is being well received throughout the country. There is a special demand for the number for use in Decoration Day celebrations throughout the country. Moreover, there are big orders which tell the story."

A typical notice was found in the trade magazines in 1916: "A most timely publication is 'All America,' a brilliant march by J. S. Zamecnik and one of the features of the Sam Fox Co.'s catalog. The piece has a martial swing to it and is being well received throughout the country. There is a special demand for the number for use in Decoration Day celebrations throughout the country. Moreover, there are big orders which tell the story."

A typical notice was found in the trade magazines in 1916: "A most timely publication is 'All America,' a brilliant march by J. S. Zamecnik and one of the features of the Sam Fox Co.'s catalog. The piece has a martial swing to it and is being well received throughout the country. There is a special demand for the number for use in Decoration Day celebrations throughout the country. Moreover, there are big orders which tell the story."

A typical notice was found in the trade magazines in 1916: "A most timely publication is 'All America,' a brilliant march by J. S. Zamecnik and one of the features of the Sam Fox Co.'s catalog. The piece has a martial swing to it and is being well received throughout the country. There is a special demand for the number for use in Decoration Day celebrations throughout the country. Moreover, there are big orders which tell the story."The publisher also saw promise in the film score snippets John had written, and soon started to publish them as well. It was a daunting task, trying to retrofit not only music, but at times full scores for films, from Cleveland Ohio, when the industry was largely in New York and Los Angeles. However, once Fox started releasing folios of Zamecnik's film cues in 1913 for distribution to and use of pianists in movies houses around the country, he established an important foothold in the industry that lasted through the 1920s. Fox also published Zamecnik songs written for some stage musicals and other theatrical productions.

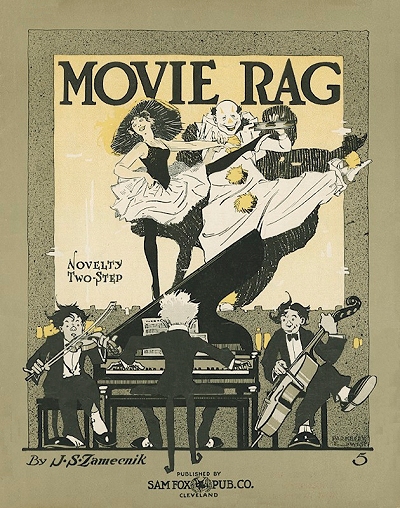

While at Fox, Zamecnik worked primarily as an arranger, including shaping many pieces by composers like Mel B. Kaufmann and Robert Wilson. He also composed both popular songs and waltzes in addition to orchestrated film cues under a variety of pseudonyms (up to 21 have been identified), perhaps in an effort to fatten up the perceived stable of Fox composers and not flood the market with his own. This was a common practice at that time. Sometimes a certain pseudonym might also be attached to a certain genre for clarification as well. However, his arranger credits usually appeared on these pieces as well as other Fox composers. He also composed in a wide variety of genres, including ragtime. Even though his Movie Rag was published separately in 1913, he managed to find a way with the clever use of repeats and minor compromises to just one page in one of the Fox folios.

Some of those popular songs were also orchestrated for use as movie cues, and he sometimes composed songs for specific films. After a while he also composed works to be used with newsreels, which gave them a whole new dynamic under the right hands. Many pieces from the multiple Fox folios of Zamecnik's works in both piano and orchestra formats also found their way into full scores for early sound films, and used incessantly in sound cartoons as well, particularly by Carl Stalling for Warner Brothers. The only big competition to this lucrative product came from Jerome H. Remick who followed Fox's lead with large folios of their own, which in spite of their scope were still not quite as successful.

Even though he had been working for Fox for nearly a decade, Zamecnik was considered just a staff member. His considerable contributions paid off handsomely in 1919, however. As reported in the August 9, 1919 edition of The Music Trade Review: "Sam Fox Publishing Co., Cleveland, O., has just signed J. S. Zamecnik, the well-known composer and arranger, to a contract covering a period of years.  It is understood that the contract calls for guarantee by the publishers of a large sum each year running into five figures. For a number of years Mr. Zamecnik has been connected with the musical staff of the above firm, of late serving as musical editor. He is considered one of the greatest arrangers in the country and has written many popular compositions, some of them having quite large sales." The length of the contract was not disclosed, but it may well have followed him to Southern California a few years later, allowing him to work from his new digs.

It is understood that the contract calls for guarantee by the publishers of a large sum each year running into five figures. For a number of years Mr. Zamecnik has been connected with the musical staff of the above firm, of late serving as musical editor. He is considered one of the greatest arrangers in the country and has written many popular compositions, some of them having quite large sales." The length of the contract was not disclosed, but it may well have followed him to Southern California a few years later, allowing him to work from his new digs.

It is understood that the contract calls for guarantee by the publishers of a large sum each year running into five figures. For a number of years Mr. Zamecnik has been connected with the musical staff of the above firm, of late serving as musical editor. He is considered one of the greatest arrangers in the country and has written many popular compositions, some of them having quite large sales." The length of the contract was not disclosed, but it may well have followed him to Southern California a few years later, allowing him to work from his new digs.

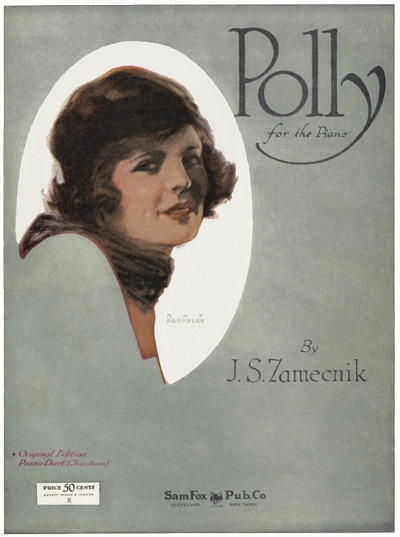

It is understood that the contract calls for guarantee by the publishers of a large sum each year running into five figures. For a number of years Mr. Zamecnik has been connected with the musical staff of the above firm, of late serving as musical editor. He is considered one of the greatest arrangers in the country and has written many popular compositions, some of them having quite large sales." The length of the contract was not disclosed, but it may well have followed him to Southern California a few years later, allowing him to work from his new digs.By the early 1920s many larger budget feature films were accompanied by custom scores commissioned for that purpose, usually for the road-show productions that used live orchestras or mid-sized ensembles. Zamecnik was engaged for cues or musical sections for several of these films. For this reason and with Sam Fox's blessing he took the family to Los Angeles in 1924, same year he joined ASCAP, where the film industry was now centered. His full scores were obviously for silent films for the next three years, including the Paramount productions of Old Ironsides and Rough Riders. Zamecnik was still employed by Fox in spite of the relocation, and wrote other pieces as well. Polly, from 1926, is an interesting and charming novelty intermezzo that became another top seller for the company, touted as the "logical successor to Nola" by Felix Arndt. Neapolitan Nights was appropriately introduced in an orchestral presentation at the Metropolitan Theater in Los Angeles in March, 1926. It didn't hurt business that Zamecnik's efforts in Hollywood eventually led to a score department being added to the publishing house.

As noted in The Music Trade Review of December 10, 1927, "Rapid strides have been taken recently by the Sam Fox Publishing Co., New York and Cleveland, in developing the musical score department of the business, the preparation of which has been handled in the past principally by John S. Zamecnik, well-known composer and arranger, who is head of the Fox professional staff. Announcement was made this week by Sam Fox, president of the company, of the appointment of Dr. Edward Kilenyi, another prominent composer-arranger, who will assist Mr. Zamecnik in working on special scores. Another new addition to the Fox ranks is Albert Sanger, who is taking full charge of the copying and extracting of scores to be issued by the Sam Fox firm. Mr. Zamecnik is at present engaged in writing scores for two large motion picture features, which will reach Broadway shortly and give every indication of equaling the success of 'Wings,' for which he also wrote the musical setting. The new pictures are: 'The Wedding March' and 'Abie's Irish Rose,' the latter film based on the celebrated play of the same name, which broke all records for long runs in New York. Dr. Kilenyi... is at present in Los Angeles assisting Mr. Zamecnik, who is thus enabled to extend his activities in working on film settings."

Now contracted by Paramount Pictures through an agreement with Sam Fox to provide and publish all of their film scores, J.S. wrote the music for the first film ever to win an Oscar for best picture, Wings, released in late 1927. Although The Jazz Singer had debuted two months before,  and a few sound films were already in theaters, Wings still gained much notice as an essentially silent film with an added soundtrack. In this sense, Zamecnik became one of the first in his field to compose a full underscore for a film that would be used in perpetuity, rather than at the whim of a theater music director. Fox also published the score for performance in theaters not equipped with sound, something much to the composer's preferences, and some 4,000 copies were distributed. The theme to the movie was published for piano in sheet music form with lyrics by Ballard Macdonald.

and a few sound films were already in theaters, Wings still gained much notice as an essentially silent film with an added soundtrack. In this sense, Zamecnik became one of the first in his field to compose a full underscore for a film that would be used in perpetuity, rather than at the whim of a theater music director. Fox also published the score for performance in theaters not equipped with sound, something much to the composer's preferences, and some 4,000 copies were distributed. The theme to the movie was published for piano in sheet music form with lyrics by Ballard Macdonald.

and a few sound films were already in theaters, Wings still gained much notice as an essentially silent film with an added soundtrack. In this sense, Zamecnik became one of the first in his field to compose a full underscore for a film that would be used in perpetuity, rather than at the whim of a theater music director. Fox also published the score for performance in theaters not equipped with sound, something much to the composer's preferences, and some 4,000 copies were distributed. The theme to the movie was published for piano in sheet music form with lyrics by Ballard Macdonald.

and a few sound films were already in theaters, Wings still gained much notice as an essentially silent film with an added soundtrack. In this sense, Zamecnik became one of the first in his field to compose a full underscore for a film that would be used in perpetuity, rather than at the whim of a theater music director. Fox also published the score for performance in theaters not equipped with sound, something much to the composer's preferences, and some 4,000 copies were distributed. The theme to the movie was published for piano in sheet music form with lyrics by Ballard Macdonald.In an April 12, 1928 review in the Los Angeles Times, both the score and the sound effects were given notice: "Three factors not usually recognized by the average audience are pre-eminent in 'Wings,' the war film at the Biltmore. These are the sound effects, the music and the remarkable photography. Effects in pictures are easily over-emphasized, but in 'Wings' the droning of motors adds so materially to the illusion of flight that the orchestra actually stops playing at two places in the film and the scenes unfold to the sound of roaring engines alone. To create a musical score for such a picture as 'Wings' was a task which only the cleverest composers could undertake. Paramount chose J.S. Zamecnik for the work. The work required six full months of Zamecnik's time and the assistance of six skilled musicians."

The advent of Paramount's Wings, Warner Brothers' The Jazz Singer and MGM's Broadway Melody made the need for composers of Zamecnik's caliber obvious. Until the late 1920s, most of them were still based in New York because most of the publishers were located there, as was Broadway, a very needy source in terms of new music. However, as noted in the Los Angeles Times on December 9, 1928, the migration was clearly underway because of the potential of sound films with music in them to reach more people around the world.

Hark, Hark! The piano tuners are in town. Tin Pan Alley has come to Hollywood. That picturesque street in the Forties [originally the Twenties] in New York, where for years song writers and piano thumpers have held forth in their tuneful glory must be about as quiet and deserted as a pathway in a New England graveyard.

For judging from the announcements which daily roll forth from the film studios, all the song writers who ever set a note to music sheet, all the fair-haired lads who ever thumped a piano down in McGuire's Cafe, have come west to write theme songs and hit songs for the new talking and singing pictures. Whether the available supply of baby grands and uprights in Los Angeles will prevail, whether the music stores will stand the strain, remains to be seen. Tin Pan Alley is here.

Those writers who have not donned their second best suit for travelling, packed away the red flannels in the cedar chest to come to California have joined the New York offices of the various film organizations.

One way or another, they have gone to work for the movies.

|

This sudden and impressive need for songs for pictures has followed the advent of the talkies. Every talkie that goes out must have its theme song synchronized with the film. Where before a theme song could be enjoyed only in the larger cities where good orchestral accompaniment was available, now it belongs to the picture and can be heard in any theater where there is sound-reproducing equipment. In the past, theme songs were not always a part of synchronization. They were often numbers dedicated to the star of the picture. This is still true today to some extent.

Hit songs now are coming from the movies and where thousands heard them before, millions of people are hearing and humming the new melodies within the space of a very few months...

Paramount song writers include Walter Donaldson, Wolfe Gilbert, Richard F. Whiting, Leo Robin, Hajos, Savino, Carbonarro and [J.S.] Zamecnik. Walter Donaldson is probably one of the most prolific song writers of the day. With Wolfe Gilbert, he was responsible for "Out of the Dawn," theme song for "Warming Up." Whiting is best known for his hit, "Japanese Sandman..."

Theme songs for pictures are not new. Synchronized scores for pictures have been in use for years, as long ago as "The Birth of a Nation," in fact. D.W. Griffith was one of the first to use them. Once in an interview he said: "Don't ask me about my picture, ask me about my music."

Interestingly enough, theme and hit songs of the pictures seem to be without exception of ballad nature. [They] are not "Hotsy, Totsy," "You Gotta See Mamma Every Night" songs. They are instead sentimental in nature.

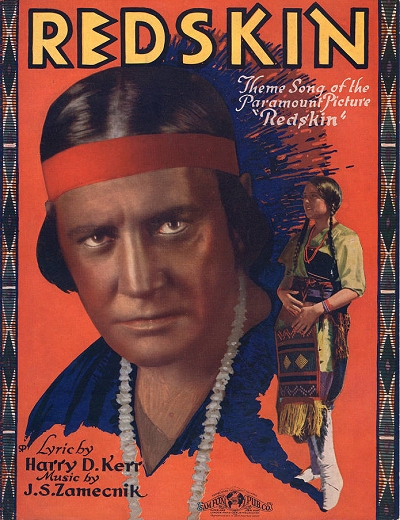

The triumph of Wings was followed by another film spectacular, albeit also a silent picture with a recorded score. Redskin, again produced by Paramount was premiered in 1929 with a Movietone soundtrack. Shot in New Mexico, Arizona and California, this sweeping saga was presented in two-strip "natural" Technicolor, and Zamecnik's work may be considered as one of the first of the Western genre underscores. While many have since pointed to the talented Max Steiner as the true originator of the active film underscore, starting with King Kong in 1933, there are critics who give some credence to J.S. Zamecnik in this role, even though, or because scoring for a film without dialog does present a different set of challenges. Paramount, in particular, was very happy with their star composer, and many early critics of sound films had similar praise for Zamecnik's scores.

Some of the other films J.S. scored were in the beginning of the sound era, and even though as with Wings and Redskin they had no dialogue, the producers chose to record the score to a soundtrack for distribution as a "sound" film. This frustrated John to no end since he felt people should be exposed to the vibrant sound of a full orchestra in the theater, rather than a tinny soundtrack from poorly amplified speakers. In some cases his score (now often referred to as an underscore) was laid down under dialogue and noisy effects, adding to his frustration. Among these was Abie's Irish Rose, The Wedding March, and the alpine drama The Betrayal.

adding to his frustration. Among these was Abie's Irish Rose, The Wedding March, and the alpine drama The Betrayal.

adding to his frustration. Among these was Abie's Irish Rose, The Wedding March, and the alpine drama The Betrayal.

adding to his frustration. Among these was Abie's Irish Rose, The Wedding March, and the alpine drama The Betrayal.Yet as an arranger and conductor, J.S. was kept busy in Los Angeles, frequently appearing at local concert venues, and at times conducting his own works as well. He was heard on various Southern California radio stations as well from the late 1920s to the mid-1930s, including KFI, KFAC, KNX, KECA and KMTR. As the Great Depression set in around 1930, radio became a primary source of entertainment for many people, followed by movies, but the recording industry suffered greatly as a result. Few of the broadcasts that J.S. participated in were recorded, so the best record of his works at that time remains in the film scores he contributed.

Zamecnik retired from composing for the most part in 1933 after scoring The Power and the Glory, working only occasionally as a consultant or arranger and continuing his radio appearances. As of the 1940 census John and Mary were living near West Hollywood, California, with John still claiming to be working as a music composer. The 1950 census showed him at nearly age 78 still listed as a music composer and publisher. John stayed in the Los Angeles area for his remaining years, but was frustratingly largely unknown at the time of his death except among the remaining cadre of early film composers and silent era pianists. His official obituary printed in the major papers after his death at 81 in 1953 noted that he had composed the scores for Wings and Abie's Irish Rose, but little else. John Zamecnik was entombed at the Inglewood Mausoleum near Los Angeles International Airport.

J.S. Zamecnik left behind perhaps 2000 individual compositions from the frequently used mysterious eight bar Pizzicato Misterioso to his fully developed scores that set the template for future film composers. He also left a great deal of influence on ragtime from his early Movie Rag to his best-selling 1926 composition Polly, a piece that was known to pianists from recordings only until it was released in 1929 to vigorous sales. Zamecnik helped embody the integration of popular music with traditional forms, broadening the audience for these forms of music, and sometimes subliminally reaching them through their exposure to it in the movie houses. His work also underscored, literally, how important the proper music was to setting a mood for a particular moment in a movie, rather than just a hodgepodge of popular tunes or rags played underneath.

One of the best exposures to his works these days is in part a tribute from Carl Stalling who used several Zamecnik cues, both credited and largely unknown, in many of the Looney Tunes and Merry Melodies cartoons of the late 1930s to the mid-1950s. Stalling, who started with Disney in the 1920s, picked up the clear notion from Zamecnik that even in animation the music should properly fit the scene, even if it was in the form of clever association by pun. But Zamecnik's influence was also felt in the great reach that Fox Music was able to maintain throughout the world from the unassuming yet important locale of Cleveland, Ohio.

For a great example of Zamecnik's work, one only needs to turn to his score for the 1927 film Wings, which was recently re-orchestrated and reunited with the picture in 2011 through the valiant efforts of San Francisco pianist and silent film historian Frederick Hodges. Even before the often lauded score for King Kong from the hand of Max Steiner, it is clear that Zamecnik understood the relationship between the music and the screen action, giving an emotional thrust to the road show version of the film that would have been greatly diminished without the careful thought he put into it. This is a highly recommended example of Zamecnik's legacy, which is now available on DVD and Blu-Ray in a stunningly recorded 5.1 digital track complete with perfectly synchronized sound effects (which Zamecnik sometimes had a hand in) by Star Wars sound designer Ben Burtt. Hopefully more such works will be resurrected as these stellar films are restored beyond their original brilliance.

Some of the legwork on Zamecnik's personal information, outside of the lists this author compiled and what is available in public records, should be largely attributed to historian Rodney Sauer of the Monte Alto Motion Picture Orchestra, which has many fine recordings out of film music including much of Zamecnik's body of work. Additional information came from the Sam Fox archives and various Fox histories. Sam Fox Music is not affiliated with the 20th Century Fox Film Corporation.

Please note also that a complete list of Zamecnik's works would require pulling titles out of the many books and separate film cues he published, so what is included here represents his separately published compositions or film cues. Some represent crossover since he re-used some of his songs as cues and rewrote cues as songs. The list is merely an attempt at scope, and hopefully fairly representative of his larger body of work. Verifiable additions are welcome at all times.

Selected Ragtime/Song Compositions

Selected Ragtime/Song Compositions